Return of the Storm God - Chapter 10a

From Pyramids to Ptolemies: How Natural Science encoded in myth evolved into proto-religion in Egypt

Introduction

By this point in this book, our method is established. When archetypes are treated not as isolated myths or local inventions but as expressions of a single Drift pattern, a structural consistency emerges across Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and even China. In previous chapters we have cross-checked this pattern in language, number, glyph, and myth, and tested it against later survivals. With this foundation in place we can now return to Egypt – the original centre – with clearer eyes.

Here, from the Pyramid Age to the Ptolemies, the archetypes can be examined not through the distortions of later theology but as they first operated. Symbols such as the twisted flax – reduced to a mere ‘rope’ or ‘wick’ in modern lists – can now be seen as living forms, deployed by people who experienced them as processes, not abstractions.

Typology is as much a key as etymology. Egyptian culture did not evolve out of disconnected local cults but out of an interlaced system of correspondences in which the same archetypal forms recur across different domains of life. Consensus Egyptology gives us valuable data – the dating of pyramids, the succession of kings, the catalogue of deities – but because there is no single codified text like the Bible, the material survives as a mosaic of inscriptions, ritual formulae, epithets, and images. Each sign was originally a condensed picture of an idea rather than a fixed word-to-letter equivalence.

Meaning for the Egyptians was first observed in nature, not in lexicons. They saw correspondences in duality – water and sky, breath and fire, body and soul – and wrote them down as shapes. To ‘walk like an Egyptian’ is therefore not to mimic a curious gait, but to inhabit a mind that created one of the most advanced and elevated natural sciences of the ancient world. Even today their calendar – the oldest continuously used solar year – resists simple reconstruction; it sits at the overlap of observation, ritual, and cosmic symbolism.

This chapter therefore proceeds on the working assumption that the initiates and priesthoods of Egypt were deeply concerned with archetypes and correspondences. They observed the natural world – earth and sky – and projected these patterns into their view of the afterlife. A shape, a number, a word held a spectrum of meaning. In modern codified languages a single word points to one or two definitions (‘set’ may be a verb, or a noun for a badger’s lair), but in Egypt a single archetypal sign could hold an entire concept, a nexus of correspondences, because it represented a living archetype rather than a discrete ‘meaning.’

To decipher Egyptian thought, then, we must approach the evidence from multiple tangents – glyphic, linguistic, astronomical, ritual. With a typological method, and by tracking hydronyms and sound-shifts across regions, new etymologies and continuities can arise. But we must also be explicit that some of these derivations are explorations, not proclamations of proven fact; even if continuity indicates the highest likelihood.

The Egyptians have been read by later initiatory orders – from Hermetists to Freemasons – as the earliest masters of symbolism and of a science of nature that fused observation with sacred narrative - and with the Babylonians as not only the earliest scientists but also the earliest magicians. The following chapters do not treat them as ‘occultists’ in the modern sense, but as a people who encoded their understanding of the world in a symbolic grammar. Out of these roots later esoteric and ‘occult’ systems drew their language of pillars, torches, glyphs, veils, and initiations. By returning to Egypt with this typological lens, from the pyramids to the Ptolemies, we can begin to recover how such symbols functioned at their source.

We now have a greater insight into the established history and chronological development of belief that would later become the basis for the Roman Bible and thus the Judeo-Christian canons.

Archetypal Method and the Psychology of Symbols

Our approach stands within a recognised lineage of archetypal psychology. From Freud’s discovery of the symbolic logic of dreams to Jung’s formulation of the collective unconscious, modern psychology has shown that certain images, numbers, and ideas evoke universal responses. They do not belong to a single culture or language: they are structural patterns of the psyche. Jung called them archetypes - forms that carry meaning long before they are given names. A mother, a serpent, a pillar, a spiral: these are recurring expressions of how the human mind perceives its own life within nature.

We are applying this same framework retrospectively to the ancient Egyptian initiates. Their environment was different, their language pictorial rather than alphabetic, but the psychology was recognisably human. Where modern people experience such patterns largely in the subconscious - through dreams, art, or intuition - the Egyptians expressed them consciously through symbol and ritual. What our depth psychologists find hidden beneath reason was, for them, the living surface of religion and science.

The Egyptian priesthood worked from observation. Their land offered continual demonstrations of transformation: the Nile’s flood and retreat, the sun’s daily rebirth, the metamorphosis of seed to stalk and corpse to spirit. In these natural cycles they recognised patterns of death and renewal that mirrored their own inner life, which further mirrored what they observed in Nature. Thus, the simplest forms - a circle, a spiral, a flame, a pillar - became vehicles for profound insight. They did not separate physics from metaphysics, or psychology from cosmology: all were facets of a single field of correspondence.

Furthermore, we also recognise the practise of shamanism across the world throughout history. Mystical visions, often under the influence of hallucinogens, brings imagery from a deep unconscious to the conscious level. The closer to one’s innermost archetypal mind one is, the greater a sense one has of conscious meaning and connection with a wider spectrum of one’s reality. We should not simply assume that everything a culture held as intelligible or sacred was strictly through a five-sense interaction with their environment and wider observation of the universe. Inner, or psychic experiences have been a foundational reality of cultures throughout history. We do not reject the psychic realm as a valid mode of experience and source of information and wisdom. Myths of an afterlife are no mere projections of observed nature into the life after death, if one’s reality involves the acceptance of the presence of ghosts and reports of apparitions, trance mediumship, or information from shamans whose wisdom derive from mystical states through encounters with elemental beings or the souls of the dead. Whether or not consensus academia accepts the existence of mind and soul after death is of little impact to this author, whose own acceptance of the psychic and ‘supernatural’ are derived from direct experience. But one must still consider the data and evidence on its own terms. Ascribing abstract mysticism where a grounded simpler evidence-based explanation serves better is often misleading, and leads to the very ‘magical thinking’ that religions are built upon.

Our typological method, then, treats the ancient Egyptian symbols as psychological diagrams as well as scientific pictorial illustrations. Each glyph or mythic image embodies a principle that resonates both outwardly in nature and inwardly in the human mind. The Djed is stability; the Eye is perception; the serpent is nature’s waveform and wisdom. When we read them in this way, Egypt’s ‘magic’ and ‘ritual’ cease to be superstitions and become early expressions of a unified science of consciousness.

In approaching a glyph such as the twisted flax, we must remember that we are dealing with a people whose eyes were trained to see layers of meaning in every line. To us, a sign is either a rope, or a wick, or a phoneme; to an Egyptian initiate it was all of these and more. The same looping form could recall the shape of an eye, a tendril of vine, the coils of a serpent, the wake of a fish, a fish itself or the spiral of eternity. Nothing in their world was ‘just’ an object.

This is not conjecture. Egyptian art and writing show that scribes and priests deliberately played with this visual and phonetic richness. Many hieroglyphs have ‘determinatives’ which are not letters at all but added images to suggest a sphere of meaning. A single word might be written with three or four pictures, each reinforcing a different correspondence. Modern scholars call this ‘semantic range,’ but for the Egyptians it was a living practice: one sign, many echoes.

Given this habit of mind, it is reasonable to assume that when we notice multiple archetypes latent in a single glyph today, we are not projecting anachronistically. We are glimpsing a fraction of the same spectrum of correspondences they themselves cultivated. In a landscape where the Nile snaked like a serpent, papyrus rose like a spear, and the sun was born each dawn from a lotus, shapes were read as processes and beings, not inert lines.

Therefore, when we examine the twisted flax glyph, we will not treat it as a ‘one-to-one’ symbol but as a field. Its spiral can be a wick, a vine, an eye, a fish, a seedhead, a flame, a dual pathway of recurrence from a source of duality – each resonance part of its archetypal load. In the following section we will explore how this one small sign – so easily overlooked – condenses the Egyptian understanding of transformation, breath, and eternity.

Flax in the Life and Death of Early Egypt

Before it became a glyph, flax was a cornerstone of Egyptian life. Archaeology shows that wild flax (Linum usitatissimum) was gathered and spun in the Nile Valley long before the dynastic age. At sites such as Badari, Merimde, and Naqada, linen fibres and spindle whorls appear by the fifth millennium BCE, making Egypt one of the first regions where the plant was cultivated and processed systematically.

Flax thrived in the Delta’s seasonal wetlands, and its thread was strong, cool, and easily dyed - perfect for the desert climate. By the Old Kingdom it had become Egypt’s national fabric: used for garments, sails, temple hangings, and the wrappings of the dead. Excavations at Gebel el-Silsila and Saqqara have produced whole bolts of fine linen, some so tightly woven that a square inch contains over a hundred threads.

Its ritual role was even older. At Hierakonpolis and Mostagedda, linen shrouds have been found around naturally desiccated burials dating to around 4400 BCE. These simple wrappings pre-figure later mummification. The use of flax for this purpose was not practical alone; it was symbolic. Linen was clean, pale, and renewable - a plant reborn each year from seed - and so became the natural emblem of purity and resurrection. It was absorbent and aided in the drying of the body in order to preserve it, and later became an essential part of preservation of the corpse in the funerary rites of the pharaohs and the wider population.

By the time of the dynasties, the association of flax with the afterlife was absolute. Temple inventories list linen as a sacred commodity alongside oil and incense, and texts speak of the gods ‘clothed in white linen.’ The shrouded body of Osiris is described in the same terms: bound in flax, anointed with oil, awaiting the breath of life.

Thus the flax plant entered every sphere of Egyptian existence - worn by the living, woven into sails that carried the dead upstream to Abydos, and wrapped around the body for its second birth. When the twisted flax glyph later came to stand for the phoneme ḥ, it carried with it this entire world of association: the plant of light and purity, the thread of life, the fabric of eternity.

Flax and the Wider Drift of Culture

Flax was not confined to the Nile valley. From the earliest Neolithic settlements on the Euphrates to the shores of the Aegean, the plant accompanied the spread of agriculture itself. Archaeobotanical finds from Jarmo and Hassuna in northern Mesopotamia, Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, and Susa in Elam show that flax was being cultivated and processed as early as 7000 BCE. In each region it served the same practical triad: fibre, oil, and seed - textile, lamp-fuel, and food.

Because it was both everyday and indispensable, flax soon entered the language of myth. In Mesopotamia the goddess Nisaba, patron of grain and writing, also presided over fibres and weaving; her temple offerings included flax and oil. The Sumerian word gish-shub covers both ‘flax’ and ‘cord,’ a reminder that the thread and the written line were felt to share a single origin. Across the Aegean world, the Linear-A and later Greek words linon and linum (Latin linum) derive from this same Near-Eastern root. The Greek Linos, a mythic son of Apollo who taught song and lament, personified the woven thread as sound; the connection of flax with voice, music, and fate persisted into the image of the Moirai, the Fates, spinning the thread of life.

The plant’s dual use - for oil and for cloth - gave it a special place in ritual economies. In both Egypt and Mesopotamia lamp wicks of flax burned before the gods, a material bridge between substance and light. In Anatolia and the Levant linen wrappings clothed votive figures; in the Aegean, linen cords sealed tombs and temple offerings. By the Bronze Age the same fibre linked sacred and domestic life from Sumer to Mycenae.

Flax was thus one of the quiet carriers of the ancient world’s symbolic vocabulary. Wherever it grew, it joined utility to cosmology: a plant of purity, light, and renewal, used to bind, to clothe, and to illuminate. Its fibres travelled with the Drift Culture westward, leaving traces in language, textile, and myth - evidence that a single humble plant could weave together the civilizations of the Near East and the Mediterranean. It later emerged as a motif in Chinese culture and language (see Appendix VII).

In Egypt the role of flax reached far beyond the practical. It was the chosen medium of sanctity. The priest entered the temple in linen alone; the gods were described as ‘clothed in white.’ Linen hung before the shrines as a living membrane between mortal and divine. Every bolt of cloth embodied the same principle that governed the universe: purity through refinement, light drawn from matter. In funerary ritual, the body wrapped in flax became a wick prepared for the eternal flame - matter readied to receive spirit.

The twisted-flax glyph (ḥ) therefore stands not merely for a sound but for a process: the spiral of transformation through which substance becomes luminous. Its shape - two strands wound together - embodies duality held in balance, the tension by which the cosmos itself was sustained. The same act that bound the corpse in linen bound the temple lamp’s wick; both were gestures of ignition. The Egyptians did not separate craft from theology. Every thread spun from flax repeated the act of creation: breath and fibre joined to make light.

We have identified a continuum running through Egyptian and wider Drift-Culture mythology: the goddess embodies fluidity and ratio in Nature - water, movement, the life-essences - while the masculine principle represents form, permanence, and the channel through which the fluid moves. In the heavens these polarities interchange. A star may appear as masculine or feminine - or both. The constellations are states of relative permanence, static forms in the firmament; yet when they move through their cycles they express the feminine polarity of motion and renewal. Orion, always masculine in the Drift Culture, was the archetype of light, stars, life, and death. But he exists only within - and because of - the greater feminine field, the sea of space.

Thus the flax wick is the perfect emblem of divine union. In its dry, inert state it is the product of that fusion: a plant born from the death of the god, revived by the waters of the goddess. When dried to a husk it awaits re-animation by the oil, and when kindled it releases the sacred light and heat - feminine energies expressed through the ambiguous principles of illumination and warmth. This mirrors the primary archetypes of light from above: the day-sun and the night-stars.

Throughout the Drift Culture one of the most consistent rites was the lighting of a flame - a flax wick in an oil reservoir - kept perpetually burning as the eternal flame. Continuity and assurance of return were vital to early humanity, as they remain today. Change outside human control signified calamity and the collapse of order. To the ancient mind, the patterned motion of the stars and their reflection on earth guaranteed the renewal of the rains and crops, the maintenance of city-state and cosmos alike. Stability was the measure of Ma’at. To guard a flame that never died was therefore entirely logical: a visible pledge that order endured.

This idea is found everywhere the Drift Culture touched. In Egypt, the sanctuary lamp of Ra was tended by priests within the inner chambers of the temples, its flax wick fed by sacred oils as the terrestrial counterpart of the sun’s light. In Mesopotamia, the priests of Shamash and Nusku maintained fires that burned day and night in ziggurat shrines, representing both the solar eye and the judgement of divine law. The Persian Ātar, the holy fire of Ahura Mazda, became the visible body of eternity in Zoroastrian ritual; every temple held a flame that could never be extinguished, renewed from generation to generation. Among the Greeks, the hearth of Hestia was kept perpetually alight in each polis, the civic flame lit originally from the Delphic fire. Romans enshrined the same principle in the cult of Vesta, whose virgins guarded the city’s eternal hearth under penalty of death should it go out. The Hebrews maintained a lamp before the Ark - the ner tamid, the perpetual light - later mirrored in Christian altars where a single flame marks the divine presence.

Across Asia the motif persisted. In India, the Vedic Agni was invoked as the living flame that carries offerings to the gods, the fire of sacrifice never to be quenched. The same devotion passed into Iran and then into later temples of the East, where lamps burned continuously before images of deities. Even in the far reaches of China and Japan, temple lamps and incense fires symbolised the unbroken breath of Heaven. The act of tending the flame was everywhere the same: a daily re-enactment of cosmic balance, the affirmation that light endures through darkness.

The universality of this observance reflects more than coincidence. It arises from a shared psychological and cosmological need: to materialise permanence within change. The steady flame was the axis of the world made visible, a small and controlled echo of the great fires of sun and star. In its flax wick and oil the ancients recognised the union of substance and spirit, earth and sky. To keep that union alive in miniature was to maintain the order of creation itself.

The flaxen wick, which in Egyptian script itself denotes eternity, arises naturally from this archetype. Its typology and psychology fit perfectly within the Egyptian mindset. That this eternal principle is bound to light and heat, and that ḥ as Hu - the breath of life - is written with the flax glyph, aligns exactly with the same logic. The divine name Ihuh, the proto-form of the later Hebrew YHWH, carries the same breath-root, as does heh in Hebrew, another form of the aspirate denoting spirit or breath. Across these languages the pattern is unbroken: the breath that animates, the wick that conducts, the flame that endures - the eternal triad of creation.

It should no longer require catalogues of examples to recognise why the lighting of wicks has accompanied ritual from the earliest sanctuaries to the ceremonies of the present day. The act itself is self-explanatory: a deliberate union of matter and spirit, of substance rising into flame. In every culture the lamp or candle stands for life sustained, for necessity transformed into divinity through a simple human gesture. To light a wick is to mirror creation; to keep it burning is to affirm continuity.

Seen in this light, the twisted-flax glyph of Egypt cannot be dismissed as a mere phonetic sign. It is the written embodiment of that gesture - the conduit that joins the earthly and the eternal. The Egyptians captured in a single image the mystery that later ages preserved in the candle, the sanctuary lamp, and the eternal flame: that life, breath, and fire are one process, endlessly renewed.

The Flax Twist and the Vesica of the Goddess

Let us now appreciate that the twisted-flax glyph bears witness to profound archetypal significance in ancient Egypt – a symbol of eternity, life, and creation. Typologically it is all-encompassing: a Djed-like sign of the god-principle, a channel through which the light and life of the goddess flow. Any Egyptian initiate, versed in the correspondences of nature and ritual, would have recognised within this simple figure a complete cosmology. It is not merely a phoneme but a glyph of process, a visual key to the laws by which spirit animates matter.

Commonly catalogued in academic lists as a rope or ligature, the sign in truth carries a far deeper meaning. Its spiral form, looped above and twisted below, mirrors the vesica piscis, the divine aperture of emergence. The image expresses the eternal rhythm of duality joining to create a third – the field of generation itself. The same curve defines the opening of the lotus, the contour of the eye, the seed-pod and the womb. To the Egyptian mind, geometry and biology were one continuum; the shape of life in nature was also the shape of creation in heaven.

Within this deceptively simple form the initiate would discern multiple layers of correspondence. The upper loop suggests the vesica – the goddess’s gate of emergence, the almond of birth and light. The paired, intertwining lines recall serpentine energy, the twin forces rising through the Djed pillar, the breath and current of the world ascending through form. At the base, the two threads divide yet remain bound: duality defined, tension contained, the foundation of manifestation. The whole image is therefore a diagram of becoming – a single movement from grounded matter through union into illumination.

Its meaning unfolds through function. The glyph represents flax, the fibre that clothed the living, wrapped the dead, and, twisted into a wick, carried oil to flame. The same plant that grew from the waters of the Nile became the bridge between the earthly and the divine. When dried it waited inert; anointed with oil it came alive; set alight it released the eternal fire. The process repeats the cosmogony itself: substance quickened by essence, form by breath, the masculine pillar by the feminine field.

To read this sign, then, is to witness the whole cycle of life in miniature. The Egyptian ḥ-glyph is at once fibre, wick, serpent, axis, and eye. It embodies both the permanence of the Djed and the motion of the goddess’s current. The twisted flax is the thread of eternity, the wick of creation through which the gods breathe their light into the world.

The Flax as Archetype and Continuum

The same twisted-flax archetype reappears far beyond Egypt, woven through the material and symbolic record of the wider Drift Culture. It is carved on seals, impressed into pottery, and cast in metalwork from Mesopotamia to the Aegean. In each instance the plant is rendered not merely as vegetation but as a diagram of emergence - three rising shoots from a single stem, balanced and symmetrical, each reaching upward from a wavy ground line that represents the water or earth of origin. This triform arrangement embodies the same law of ratio found in the Egyptian glyph: the ascent of life from dual base to triune balance, the geometry of breath and renewal.

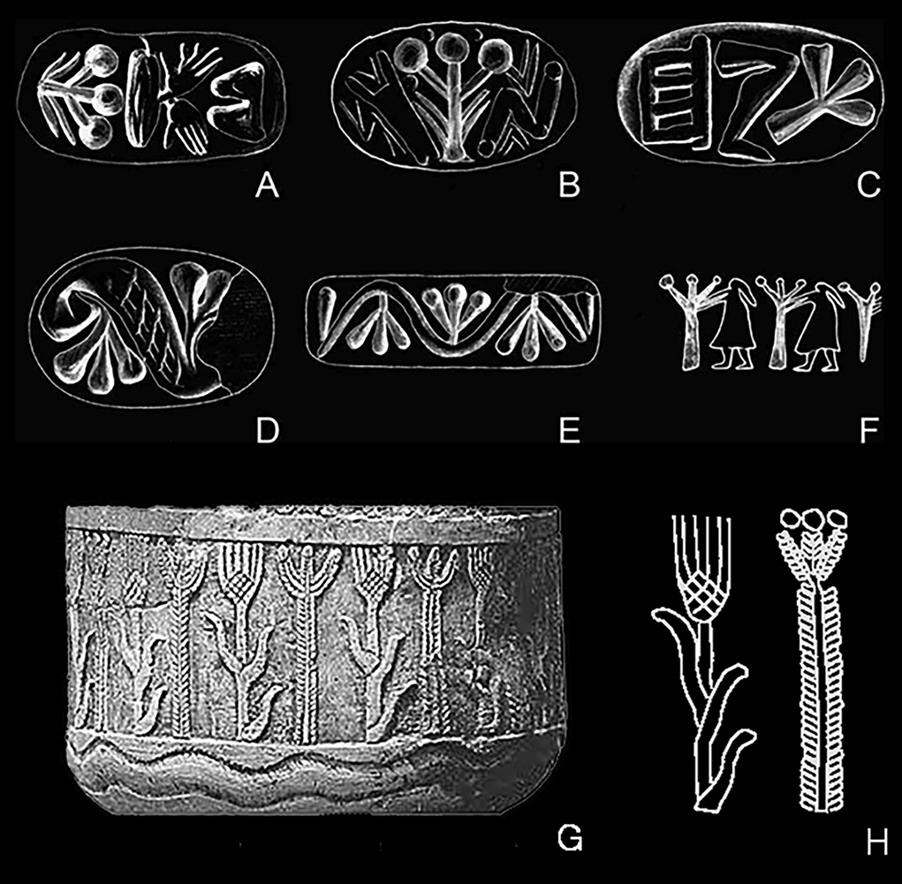

A–E: Flax motifs on Aegean seals display triform symmetry and upright emergence (CMS IV 135b; CMS X 312c; CMS II,2 259; CHIC 038–010–031; CMS III 186b; CMS III 237a).

F: Seal from Susa, Mesopotamia (after Breniquet 2008) showing the triform flax associated with human figures in celebratory or ritual pose.

G–H: The Warka Vase (Uruk, c. 3300 BCE) depicts the tripartite stalk in a field context, bordered below by the wavelike boundary of water. The motif forms part of the processional imagery associated with the goddess Inanna, who embodies the generative and watery principle of life.

As discussed in Chapter 6, the Warka Vase encodes not only a ritual processional scene but also the use of harmonic ratios in visual form - centuries, perhaps millennia, before the formal articulation of geometry in the Greek world. The flax stalks carved upon its surface appear in triform arrangement, three shoots rising from one stem. This configuration mirrors the later Algiz rune of northern Europe, the shin in Hebrew and the Chi (Χ) symbol of the Roman and Christian world via its runic counterpart. The plant itself becomes a living vesica, a vertical manifestation of emergence from duality into triune balance. Rooted in feminine soil and crowned with radiant breath, it is both botanical and cosmological.

Across Sumerian, Aegean, and later Mediterranean art this motif recurs with extraordinary persistence. The flax plant was not only cultivated but enshrined as a sacred emblem of the feminine principle - its fibre woven into the garments of priestesses and its oil feeding the ritual flame. The same image passed from Inanna to Isis, from the temple lamp to the eternal flame, and finally into the symbolism of later faiths. The triform stalk becomes the prototype of the candlestick, the menorah, the triple lamp of the sanctuary, and even the stylised fleur-de-lis of Christian art.

It is therefore no exaggeration to call flax one of the great carriers of the sacred code. Its fibres link the earliest agrarian rites of Mesopotamia with the eternal flames of Egypt and the Mediterranean. In its physical properties - strength, fineness, luminosity - and in its symbolic resonance as the conduit between earth and light, flax unites the practical and the divine. It is the tangible thread through which the feminine principle of life, the goddess herself, continually expresses renewal.

The flax is frequently represented in triform, and here again the correspondences between neighbouring mythologies become apparent. The triform plant, wick, or flame embodies the meeting of duality with the third principle of emergence - exactly the pattern that reappears across Egypt, Greece, India, and even China. This symbolism deserves close scrutiny, for a flaming trident may be yet another reflection of the same archetype: the burning wick expressed as a threefold pillar of light.

In the Vedic myth of Lavanasura (or Lavana) and Vishnu, the demon Lavanasura wields a flaming trident of power and is granted eternal dominance until the Creator Vishnu intervenes through his human descendant, Shatrughna. Vishnu’s role is to preserve cosmic order and protect the universe from chaos; he is, in essence, the guardian of ma’at. As the Supreme Purusha, he also echoes Ptah, the divine craftsman and maintainer of balance, and his name contains puru, a root that some scholars have linked with pharaoh.

Tentatively, therefore, we may read the flaming trident as analogous to the burning flax wick - a triune conduit of light and spirit. In the myth it is extinguished only by the essence of the void: Vishnu enters and merges with the waters to become the greater whole. The symbolism is topologically identical to that of Ptah–Atum, in which light arises as stars from the cosmic waters. Vishnu is indeed represented as a fish, and the root Vish, as Waddell noted, corresponds with the Sumerian term for fish. The same imagery flows westward in the figure of Poseidon, who also bears a trident, conventionally dismissed by consensus as nothing more than a fisherman’s spear. Such reduction misses the multilayered meaning and the clear cross-correspondences throughout the Drift Culture. The triform or trident form is a universal emblem of the flax-wick principle - light rising from the waters, order from the void, eternity sustained through flame.

(See Appendix VII for discussion of the triform wick-glyph and its diffusion across the Drift field.)

The triform flax motif also calls to mind the Hebrew letter shin (ש), which appears in words such as Shaddai and Shemesh, and in the name of the divine as El Shaddai. Hebrew tradition tells us that shin developed from a pictogram of a tooth, yet its form - three upward strokes rising from a base - bears closer resemblance to the triform plant, the wick or flame, or the branching glyphs of Egypt than to a molar.In Hebrew shen means tooth, and appears to be the origin of why shin/sin - the triform Hebrew glyph - is said to come from a tooth. In Egyptian, the shen ring was the symbol of eternity: a circle of infinite return. (Shen is a word in China meaning ‘ring of life’, which is yet further evidence for the Drift into China.)

It is not our claim here to ‘prove’ a direct descent. But given the this book’s evidence of deliberate inversion and redaction when Egyptian material was appropriated into later religious systems, it is at least reasonable to ask whether such a shift - from a sign of cyclic eternity to a sign of linear biting - represents more than coincidence. The goddess Neheh, embodiment of eternal, cyclical time, stands opposite Djet, linear time. To recast Neheh’s symbol as a ‘tooth’ would be to invert her meaning entirely: from flowing continuity to discrete linearity, from womb to jaw.

This would fit a wider pattern already demonstrated: the same culture that glosses Ya’aqov as ‘heel-grabber’ rather than recognising an Egyptian Iah-root; the same tradition that recasts Osirian and Horian themes as Moses and Jesus; the same textual habit of presenting an inherited archetype as if it were indigenous and original. The gulf between initiatic knowledge and exoteric interpretation has always been large; the later editors of sacred texts knew that control of symbols is control of memory.

In this book we do not present such correspondences as final proofs, but as datasets to be cross-checked with the broader drift evidence. If Hebrew, like Greek and Latin, sits on a deep Egyptian substrate, then the appearance of shin, shaddai, and shen as echoes of the triform flax may be a residue of that inheritance, now hidden under layers of redaction.

In the wider Drift field the forms related to sh or s are almost always curved: the Egyptian shen-ring, the flowing sigma of Greece, the sinuous S of the Latin alphabet. Only in Hebrew does the sign become angular and is explained as ‘tooth.’ This reversal is striking. The usual development of scripts is from angular incision to curved writing, not the other way around. The Hebrew interpretation therefore appears as a deliberate linearisation of an originally curvilinear, cyclical symbol - a re-reading that replaces the eternal loop with the cutting edge. Within the context of our wider data this fits the pattern of inversion: an inherited Egyptian sign of eternity recast as a Semitic emblem of division and linear time.

Even if the trident-shaped shin does not have any deliberate association with flax in particular, the entire lineage of shin and subsequent related developments such as S and sigma makes the Hebrew interpretation as a linear form - as tooth - the unique outlier, suggestive of a deliberate redaction or curation in the official narrative, which has become the consensus.

Medjed and the Living Flax

Medjed’s figure embodies the same field principle expressed by the twisted-flax glyph. He is not a cartoon ghost or a veiled man but a risen tor-like form – a rounded, upright shape with polar points. This is the Djed in motion, the bread-loaf determinant ‘t’ rendered as a living axis. His eyes mark the polar nodes through which perception and force emerge, while his body encodes the twist – the movement within stability. Medjed is the vesica made incarnate, a torus turned glyph.

Egyptian texts that speak of weaving the body, binding the field, or wrapping the god describe this same dynamic. The act of mummification re-creates the wick: inert flax, dried and lifeless, anointed with oil so that light may rise again. The linen shroud is both garment and conduit; the oil of Isis animates it. The anointed body becomes the krst – the completed Osirian form ready for return through the waters of the goddess. The same process that brings a lamp to life revives the soul: fibre, oil, and flame united through breath.

In this schema Medjed stands as the hidden force of resurrection, the unseen striker that animates form. His name echoes Khufu’s Horus title Medjedu, linking him to the builder of the pyramid and to the ritual of the eternal flame within it. The parallel is precise: the ascending axis, the bread-loaf determinant ‘t’ that seals and completes. Medjed’s shape mirrors the high-bread sign, the enclosure that protects the spark of life. He is the unseen tip of the pyramid, the benben itself, where the first light breaks through matter.

Seen through this lens, the pyramid, the flax wick, the mummy, and the god share one typology: matter prepared, anointed, and kindled by spirit. The symbolism is not occultism but natural philosophy rendered in sacred shorthand. What modern readers call ‘mystery’ was for the Egyptians a scientific observation of process – how form conducts life. The myth of Osiris, the geometry of Giza, and the figure of Medjed all express the same equation of renewal: the passage of energy through form, whether as the renewal of life on earth or the kindling of the soul after death for rebirth in the afterlife.

Medjed endures as a reminder that the ancient language of flax, oil, and flame was never about death but about the continuity of life through transformation – the eternal principle every initiate sought to embody. Archetypally there is little difference between Medjed, the flaxen mummy wrappings, the flax twisted into a wick and dipped in oil, or a ritual candle burning in honour of the divine. Each enacts the same law of transference: substance quickened by essence. The very word krst embodies that sacred flow of nature – the reincarnation of life between physical forms, the everlasting cycle of return.

With the pyramid age peaking at Giza, the Egyptian vision reached its fullest expression: life, death, and return unified in one language of stone, fibre, and light. Yet after this high synthesis a long descent began. The creative impulse that had once drawn sky, river, and earth into a single harmonious order gradually gave way to formality and control. The living science of Ma’at hardened into priestly doctrine; dynasties multiplied, competing for divine legitimacy; ritual replaced revelation.

What had been the geometry of renewal became the architecture of power. The divine word was recited, not realised. The same precision that had aligned the Great Pyramid to the stars was turned inward to regulate bureaucracy and law. Over the centuries Egypt remained outwardly splendid, but the equilibrium between spirit and matter slowly faltered. The flame still burned in the sanctuaries, but it flickered behind walls of hierarchy and ceremony.

Through the Middle and New Kingdoms the rhythm of rise and recession repeated - periods of consolidation followed by civil fracture and foreign rule. Yet even in this descent the pattern endured: the gods of Egypt were adopted, translated, and re-cast by every power that entered the Nile valley. By the time of Alexander and the Ptolemies, the ancient synthesis had become the foundation of a new syncretic world, where Egyptian, Greek, and Eastern thought mingled to shape the philosophies that would define the next age.

From Khufu to the Threshold of 2181 BCE

The last great pyramids and the changing state

With Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid at Giza, the pyramid age reached its symbolic height. His name, Khnum-Khufu - ‘Khnum protects me’ - invoked the old creator-god Khnum, who fashioned life from the clay of the Nile. In his reign the unity of engineering, theology, and kingship achieved its most complete form. The Great Pyramid embodied the divine order of Ma’at in stone, aligning earth to the heavens with a precision that has never been surpassed.

Yet within this achievement lay the seed of change. Khufu’s vision gathered the entire nation into one project: a king surrounded by thousands of skilled workers, scribes, and priests, all serving a single cosmic purpose. For the first time spiritual power, economic labour, and royal authority were fused into a national system. This was the model from which Egypt’s later state religion would grow. After Khufu, the balance between living theology and administrative control began slowly to shift toward bureaucracy and priestly hierarchy.

Khufu’s immediate successor, Djedefre, built his pyramid to the north at Abu Roash rather than at Giza. His choice signalled a theological realignment. In his titulary he styled himself ‘Son of Re,’ the first king to claim divine descent from the sun god. The cult of Re at Heliopolis - the ‘City of the Sun’ - therefore emerged as the new spiritual axis of the kingdom. A priestly order dedicated to the solar principle began to rise in influence, shaping later dynasties for centuries. With Djedefre the Egyptian Pharaoh became not merely the mediator of heaven but its incarnation in light.

Khafre, another of Khufu’s sons, returned the royal necropolis to Giza. His pyramid, second in size only to his father’s, was paired with a monumental valley temple and a causeway ascending to the plateau. It was in his reign that the Sphinx - carved from the limestone bedrock beside the causeway - was almost certainly completed. Facing due east, the Sphinx gazes directly at the rising sun: the guardian of the horizon and symbol of the king’s eternal watch over the daily rebirth of Re. The lion body and human head fuse animal strength with divine consciousness; its gaze captures the first rays of dawn at the equinox. In this period the ideology of the Sun King became fully visible in stone.

Menkaure, Khafre’s successor, built the smallest of the three Giza pyramids yet gave unprecedented attention to his mortuary temple, expanding it into a vast complex of shrines, storerooms, and processional courts. The emphasis was shifting from sheer monumentality to ritual economy. The temple, not the pyramid, became the heart of the cult. Teams of priests known as hemu-ka - ‘servants of the ka,’ the life-force of the king - performed daily offerings of bread, beer, and incense to sustain the royal spirit. The Pharaoh’s afterlife became a national enterprise employing thousands, and the infrastructure of state religion took permanent form.

The final ruler of the 4th Dynasty, Shepseskaf, broke with the Giza model altogether. He built a massive flat-topped tomb at Saqqara - a mastaba or ‘bench’ - and nearby the enigmatic monument of Khentkawes I, later honoured as the mother of the next dynasty. These constructions mark the transfer of power southward toward Saqqara and the older capital of Memphis, where the administrative priesthood of Ptah was ascending. By the close of the dynasty, Egypt’s religious and political focus had shifted: the solar theology born from Khufu’s house had become institutional, and the network of cults that once served the living king had become the machinery of the divine state.

The Giza plateau thus represents both the pinnacle of Egyptian civilisation and the point of transition. It was the apex of sacred architecture and the birth of a formalised priestly system. In the Great Pyramid, the Sphinx, and the sun temples that followed, we see the transformation of a living cosmology into the first imperial religion - an achievement of extraordinary beauty and order, yet one that began the slow descent from revelation to ritual, from science of life to administration of belief.

Hetepheres I and the Birth of the Imperial Cult

The origins of Egypt’s later solar kingship can be traced to the family of Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid. His mother, Queen Hetepheres I, left one of the most remarkable tomb assemblages ever found - the gilded furniture and jewellery recovered by Reisner’s team at Giza in 1925. Her titles on those objects read:

King’s Mother, King’s Wife, King’s Daughter of His Body, Great of the Hetes-sceptre.

The key phrase, ‘King’s daughter of his body’ (sȝt-nswt n ẖt.f), is the normal Old Kingdom formula for a biological princess, not a theological claim of divine birth. The hieroglyph after nswt is the sign for king, not for god. Later writers occasionally rendered this as ‘daughter of the god’s body,’ but no such wording exists in the original Egyptian. Hetepheres was almost certainly a daughter of the previous ruler, probably Huni, which made her marriage to Sneferu a union of dynastic bloodlines rather than a declaration of divinity.

Nevertheless, her tomb marks a turning point. In Hetepheres’ generation, royal lineage itself began to acquire sacred weight. By describing herself as ‘daughter of the king of his body,’ she positioned her offspring within a biological chain of divine right - a claim that her son Khufu would elevate into theology. Under Khufu, the unity of state and faith reached its first true synthesis: the Pharaoh became the living axis between heaven and earth, and the great national project at Giza turned that concept into stone.

Thus, while Hetepheres did not proclaim herself divine, the idea of divine descent germinated within her household. What had been genealogical became theological. Her son’s reign transformed the prestige of royal blood into the first imperial cult, a system in which the king embodied the creative power once ascribed to the gods. The solar theology of Heliopolis, rising in Khufu’s time and formalised by his successors, would later codify this transformation under the title ‘Son of Re.’ In retrospect, Hetepheres stands at the threshold of that revolution - the matriarch through whom mortal kingship was first recast as the lineage of light.

The Afterlife of Khufu – The King and the Sage

Khufu’s name did not end with his dynasty. Long after his pyramid had ceased to be a royal tomb, it remained a centre of pilgrimage and legend. In the late Old Kingdom and Middle Kingdom the great monument was already called Akhet-Khufu - ‘the Horizon of Khufu.’ In that name lies the shift from history to myth: the pyramid became the visible horizon between the world of the living and the light of eternity.

Archaeology shows that a cult of Khufu persisted at Giza for centuries. Small chapels near the Great Pyramid contain votive stelae from private individuals asking for the king’s favour. Lists of priestly titles from the 6th Dynasty record ‘Servants of the Ka of Khufu’, evidence that his mortuary cult was still active five hundred years after his death. The king had become a kind of intercessor deity, honoured by common people as well as by priests - a transformation that mirrors the later pattern of saints in Christian tradition.

By the Middle Kingdom, Khufu’s memory had divided along two lines. Officially, he remained a divine ancestor, the builder of the ‘horizon.’ In popular tales, however, he became a figure of awe and fear - a magician-king who sought the hidden words of power. The most famous of these stories survives in the Westcar Papyrus (now in Berlin), written in the Second Intermediate Period but set in Khufu’s court. It tells how the king summoned the aged sage Djedi, reputed to be 110 years old and able to perform wonders: to reattach severed heads, to tame lions, and above all to reveal the number of secret chambers in the sanctuary of Thoth.

In the tale, Khufu desires this knowledge for his own tomb, seeking a pattern for eternal life. Djedi refuses to reveal the secret to the king himself, saying it is destined for the unborn sons of a priestly woman who will found the next dynasty. The story is thinly veiled allegory: Khufu, the founder of the solar state, yields the future to the coming house of the Fifth Dynasty, whose rulers would build the sun temples and inscribe the first sacred texts. The legend thus preserves the memory of a real historical transition - the movement of divine authority from the monumental pyramid builders to the theological dynasty of the sun.

The Djedi legend also marks the changing perception of knowledge in Egypt. In Khufu’s time the king had embodied wisdom; in the later tale he must seek it from the sage. The myth expresses the shift from revelation to interpretation: from the god-king as living source of order to the priest and scholar as its guardian. It is the moment when the imperial cult of Khufu passed into myth and scripture, when living science became sacred lore.

Khufu’s pyramid still dominated the skyline of the Old Kingdom, but in the minds of later Egyptians he had already become something greater and more ambiguous - the first Pharaoh to step from history into legend, the prototype for every ruler who claimed to hold the secret of eternal life.

The same pattern of deification and re-deification reappeared many centuries later under the Ptolemies. Then the memory of earlier priest-kings blurred into the legend of Asclepius, the Greek healing god who was the Hellenised form of Imhotep. Imhotep had been a vizier and architect, a priestly figure of wisdom serving Pharaoh Djoser, but even he was not originally a historical man: the name began as an epithet of a god applied to the king, later personified as a sage, and finally re-divinised as a god in his own right. In Roman Egypt this deified healer was further syncretised with the new figure of Jesus, completing the long cycle in which the attributes of the divine king were translated from pyramid to temple to gospel.

The final evolution of this nearly three-millennia revision - the completion of the long priestly re-engineering of myth into law - was the emergence of a new scripture and a new code. Its foundation was the claim that the Son of God had been an historical man, and then, by theological decree, a god-man. In him the ancient lineages converged: the new Sa-Ra, the new Djedefre, son of the divine; the new Horus-Osiris king; the new Adam-Atum; the new Moses-Osiris; the new David-Orion - the legendary yet entirely ahistoric ‘King of the Jews.’

The Return of the Djedi

Of course, mythmaking never ends; it simply changes language. The Djedi tale of Khufu - where a hidden knowledge of life and death is guarded by a wise priestly order - reappears in modern mythology through popular culture. In George Lucas’s Star Wars saga the mystical Jedi inherit the same role: guardians of an ancient energy that binds all living things. The celestial warrior, our modern Orion, becomes the Sky-walker, the messianic hero - or Heru–Horus, the son who rises in light, and whose power is light, both as spirit and sword. Across four and a half millennia, from Djoser and Khufu to Star Wars, the same Nature-based archetypes persist - birth, death, renewal, the eternal struggle between darkness and light. The setting has changed, but the pattern remains unmistakably Egyptian. (see Appendix IX).

The Priesthood Ascendant

Khufu is notable not only as the builder of the Great Pyramid, but as the founding father of organised religion - the moment when spiritual authority began to crystallise into a class of men who claimed to speak for the gods. What began as the Pharaoh’s personal communion with the divine became the prerogative of a priestly order, a body that would, over time, grow powerful enough to rival the throne itself.

From the solar temples of Abusir to the sanctuaries of Amun at Thebes, the same dynamic can be traced. The priests who had once served as custodians of ritual became administrators of theology and, through theology, of power. In the Old Kingdom they managed the estates that fed the pyramid cults; by the New Kingdom their successors at Karnak and Luxor controlled armies, fleets, and taxation. The god’s household became a state within the state.

This shift brought Egypt the same dilemma already visible in Mesopotamia: the keepers of sacred knowledge turning that knowledge into political currency. The priesthood of Amun eventually rivalled the throne itself. During the later reigns of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, the struggle between royal and priestly visions of divinity broke into the open. Akhenaten’s monotheism - his elevation of the Aten, the visible sun, above all other gods - was not merely a religious reform but an attempt to reclaim cosmic authority from the entrenched Theban priesthood. After his death the priests restored the old order, erasing his name and enthroning the boy Tutankhamun as the symbol of reconciliation under Amun.

From that moment the pattern was fixed: revelation gives way to doctrine, doctrine to administration, and administration to politics. The same process that had begun in the pyramid towns of Khufu’s age now reached its logical end. The divine science that once described the harmony of sky, river, and king had become a hierarchy of men guarding their privileges in the name of the gods.

The Fifth Dynasty – The Solar Kings and the First Sacred Texts

By the opening of the Fifth Dynasty a profound shift had taken root. The solar theology born in the house of Khufu had become the formal creed of Egypt. Every king now styled himself ‘Son of Re,’ the living image of the sun god. The seat of this faith was Heliopolis, whose priests formulated the great cosmogony of Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Set, and Nephthys - the ‘Ennead’ or company of nine gods. These were not mere myths but a language of natural philosophy, a code expressing the dynamics of creation and order.

The rulers beginning with Userkaf (c. 2490 BCE) institutionalised this vision. Beside each pyramid they raised a new structure, the sun temple, open to the sky and crowned with an obelisk representing the ray of Re descending to earth. The best preserved, that of Niuserre at Abu Gurob, contained an altar of alabaster, processional ramps, and a vast courtyard for the festival of the sun’s rebirth at the turning of the year. These were the first state temples accessible to large gatherings of people. The king, once an unseen figure within the pyramid, now appeared in the open, embodying the sun before his subjects. The cult of Re thus became a national spectacle, its theology supported by a new class of professional priests and scribes.

Our picture of this administration comes from the Abusir Papyri, fragments of temple accounts preserved in the desert sand. They record the delivery of bread, beer, meat, and incense; the schedules of priestly shifts; and the detailed management of temple estates. We can see the rise of a salaried, literate clergy - the earliest form of what we would recognise as religious bureaucracy. The Pharaoh remained the divine centre, but the mechanics of worship had become institutional.

Yet the archaeology tells another story beneath this official order. The tomb art of nobles and officials shows increasing reference to Osiris, lord of the underworld - a god who had scarcely featured in the earlier solar theology. The emphasis on resurrection through water and vegetation, so ancient in Egypt’s agrarian heart, was beginning to weave itself into the royal ideology. The priests of Heliopolis spoke of the king’s ascent to the sky in the solar bark of Re, but the people of the Delta and the valley spoke of rebirth through the body of Osiris, the grain-god who dies and rises each year with the flood. The two currents were meeting, and out of their confluence would come the classical Egyptian vision of the afterlife.

The first written expression of that synthesis appears in the pyramid of Unas (c. 2345 BCE). In its burial chambers, for the first time, sacred words were carved directly into the stone - spells, hymns, and invocations that had previously been spoken only by initiates in the temple. These are the Pyramid Texts, the earliest religious writings known to humanity. The inscriptions form a dialogue between the king and the gods: part hymn to the sun, part manual of ascension, part Osirian drama of death and renewal.

Archaeologically, Unas’s pyramid stands at the threshold of two ages. Architecturally it is modest, its masonry inferior to the giant works of Giza, yet its interior is filled with text - the inner structure of belief replacing the outer bulk of stone. The combination of solar and Osirian imagery within these texts reveals the theological compromise that would define the rest of Egyptian religion: the union of Re and Osiris, light and darkness, day and night, cyclical eternity and momentary ascent. The king becomes both - the sun rising in the east and the corpse reborn in the west.

When later historians such as Manetho (if he even existed at all and was not an invention of Roman theologians - see Appendix V) or Herodotus described Egypt as a land of priests and mysteries, it was to this era they were unconsciously referring. The doctrines they encountered in the Late and Ptolemaic periods were the distant descendants of what Unas’s priests had first set in stone. The Pyramid Texts give us the earliest glimpse into the minds of the Egyptian elite - how they understood creation, order, and the fate of the soul. From this point onward we are no longer reconstructing belief solely from monuments and symbols; we begin to hear the voices of those who lived within that symbolic world.

For researchers like Gerald Massey, who later sought to recover Egypt’s original cosmology from these very texts, this moment is the crucial hinge. Everything earlier must be reconstructed from archaeology and later echoes; here, for the first time, the inner doctrine is made explicit. But even these writings already reflect centuries of development. They are the outcome of the great synthesis that followed Giza: the transformation of Egypt’s living science of life and light into a structured theology - an evolution that would dominate the next two thousand years of religious thought. Then dominate the Current Era in another form as The Bible.

The 6th Dynasty: long reigns and the drift toward decentralisation

The next kings – Teti, Pepi I, Merenre, and Pepi II – kept the same form but ruled in a changing world. Their pyramids at Saqqara were smaller, but the temples around them grew ever more elaborate. The Pyramid Texts were copied and expanded for each ruler, showing how religion was becoming increasingly textual and formulaic.

Meanwhile the provinces gained strength. The local governors, or nomarchs, built large decorated tombs in their home regions along the Nile. Their autobiographies boast of favours received from the king – land grants, statues, and titles such as overseer of priests or chief of the nome. The king still appeared supreme, but power was now shared with a network of hereditary lords who controlled local temples and armies.

By the extremely long reign of Pepi II – possibly more than ninety years – this balance had broken down. Central authority weakened; provincial officials became semi-independent; trade routes shifted as the climate dried; and the old pyramid-temple economy could no longer sustain the whole country. When the 6th Dynasty ended around 2181 BCE, Egypt entered what historians call the First Intermediate Period – a time of divided rule, rival cults, and regional revival.

The people and their gods

Between the Great Pyramid and this collapse lie almost three centuries of profound change. Giza, Abusir, and Saqqara were not merely cemeteries but living towns of craftsmen, priests, and farmers. The workers’ villages discovered beside the pyramids show well-built stone houses and bakeries, evidence of stable, professional labour rather than slave gangs. The central idea of Ma’at – truth, balance, and order – guided both government and morality.

By the late Old Kingdom, the idea that only kings could join the gods was softening. Ordinary Egyptians began to hope for a personal afterlife. The Osiris myth, with its promise of resurrection, spread beyond the palace walls. What would become the ‘democratisation of the afterlife’ in later centuries was already beginning here.

The Fragmented State: Local Power and Mythic Diffusion (re-integrated)

The First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BCE) is usually described as an interlude of collapse between the monumental Old Kingdom and the renaissance of the Middle Kingdom. In truth it marks the first great re-organisation of Egyptian religion. When central kingship faltered, the theology that had revolved around Khufu’s solar court and Memphis’s engineers dispersed into a hundred local currents. Each nome asserted its patron god, and with this new plurality came the slow broadening of Egypt’s pantheon from royal cosmology to popular religion.

The northern house at Herakleopolis maintained the memory of Memphis and the solar kings through Re and the ram-god Heryshef, while in the south the rising Theban line adopted Montu, the falcon of war, and a little-known wind-deity, Amun. The latter’s very name - ‘the Hidden One’ - proved prophetic: he would become the invisible centre of Egypt’s later empire.

In this plural landscape Osiris moved from marginal funerary god of Abydos to the moral core of belief. His cult offered what the solar state-religion had denied ordinary people: personal resurrection and judgment. The myth of his dismemberment and re-assembly by Isis carried a message that survived the collapse of dynasties - that order can be re-made out of chaos. It was during this decentralised age that Isis began to eclipse the older fertility deities such as Hathor, Neith, and Min’s consort Qetesh, absorbing their attributes as protectress, mother, and magician. Every household shrine could imagine its dead within the embrace of Isis and the promise of Osiris.

Funerary innovation followed theology. The Coffin Texts - descended from the Pyramid Texts but now inscribed for provincial nobles - spread the Osirian formula to a wider class. In them the deceased is called ‘Osiris [N],’ proclaiming participation in the god’s rebirth. The pyramid’s cosmic ladder was replaced by a personal map of the underworld, a theology portable enough to fit inside a coffin.

Politically, the same diffusion created a new religious economy. Local temples administered their own estates; priests became magistrates and tax-collectors. The unity of Ma’at that Khufu’s architects had once fixed in stone now survived as a network of rituals maintaining balance within smaller fields. In this redistribution lay the seed of the later Egyptian trinity: Isis, Osiris, and their child Horus - a family small enough to be understood everywhere, yet capacious enough to contain all the older gods within its archetypes.

Symbol Drift in Chaos: How Religion Survived the Collapse

When the kingship of the Old Kingdom finally disintegrated, it might have seemed that the gods would fall silent with it. Yet the opposite occurred. In the absence of a single ruler the sacred order multiplied, adapting to the mosaic of new local powers. The centuries that Egypt later remembered as an age of darkness were, in religious terms, a period of diffusion and survival – the moment when theology left the palace and entered the villages.

Across the nomes the same elemental deities re-emerged under local names. The falcon of Horus became Montu at Thebes, Sopdu in the Delta, and Behedety at Edfu. The sun of Re fused with regional forms as Khepri, Atum, or Ra-Harakhty. Each cult translated the old cosmology into its own dialect, but the underlying grammar remained Egyptian: sky and earth as lovers, the sun as rebirth, the river as eternal circulation. The people did not abandon the old science of correspondences - they miniaturised it, bringing the cosmic rites into their own homes and necropoleis.

The Coffin Texts capture this transformation. Where the Pyramid Texts had been written for a single god-king, these were written for thousands of lesser men and women, inscribed on cedar planks and inner coffins. They repeated the same invocations of ascent and renewal, but now in the first person: ‘I am Osiris, I know the names of the gates.’ The voice of the priest became the voice of every believer. This was the first great ‘democratisation of the afterlife.’ The myth of Osiris – once the royal metaphor of regeneration – became the common language of hope.

The cult of Osiris at Abydos gained unprecedented prestige. His annual mysteries, re-enacting the god’s death and resurrection, drew pilgrims from every province. Processions of images and mummiform effigies carried through the desert made visible the same promise that the old pyramids had proclaimed in stone: that dismembered life could be reassembled and made whole. In these rites Isis emerged as the universal intercessor – no longer the dynastic sister-wife of the god-king but the compassionate mother who restores all souls. Her image, nursing the infant Horus, appeared on amulets and household shrines from Elephantine to the Delta. The familial triad of Isis–Osiris–Horus thus began its long ascent as Egypt’s most intelligible and portable theology.

Meanwhile the political fracture produced a new religious economy. Each provincial temple became its own treasury, mint, and archive. Priests took on administrative roles once held by the court, and pious foundations accumulated land. Theology and taxation intertwined: to feed the god was to sustain the local state. This arrangement would persist through every later dynasty, culminating in the powerful temple-estates of Thebes and Karnak.

The artistic record of the age mirrors this inward turn. Reliefs and painted coffins show the deceased embraced by Isis, protected by Nephthys, judged by Osiris – scenes that had once been the king’s prerogative now applied to every person of means. The falcon and the Djed pillar, the Ankh and the wedjat-eye, reappeared everywhere as condensed assurances of continuity. Symbol drift became the mechanism of survival: the same emblems changing context without losing meaning.

Thus the so-called collapse of the First Intermediate Period was in truth a dispersal of Egypt’s sacred field. The gods did not die; they diversified. The multiplicity of this era would later be gathered again under Thebes, but the experience of dispersion left a permanent mark. From this point onward Egyptian religion would oscillate between expansion and consolidation, between the many and the one. The pattern established here – proliferation, fusion, and eventual re-alignment – would repeat on ever larger scales, reaching its dramatic focus in the solar singularity of Akhenaten and its final synthesis under the Ptolemies.