Return of the Storm God - Appendix IX: Return of the Djedi - The Westcar Story (revised 5-11-25)

The modern Star Wars myth is ancient and entirely Egyptian - revealing much about the history of Egypt

Preface

Much like the modern films Star Wars or West Side Story - itself a retelling of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, which in turn descends from the Greek tale of Pyramus and Thisbe - the ancient Egyptian scribes were among the first to employ the familiar narrative device we now call ‘once upon a time.’ These ‘tales of yore’ offered more than amusement; they were teaching instruments through which cosmology, morality, and lineage could be conveyed in allegorical form. The Westcar Papyrus is the archetype of that tradition. It translates living cosmological principles into dramatic story, a form that later cultures would recognise as myth or sacred history. See the translations here: Papyrus Westcar – The Story

Within Egypt this narrative art had clear purpose. Each tale echoed the divine pattern of Isis, Osiris, and Horus - the cycle of loss, restoration, and renewal that expressed the natural law of return. Through such parables, the Egyptians externalised their observation of natural processes: light reborn after darkness, the seed quickened in the earth, the king renewed through death and succession. What later became national folklore - the Arthurian romances, the Eddic lays, the Vedic epics, and eventually the cinematic sagas of our own time - descends from the same root method: re-telling the universal drama of polarity and reunion in the idiom of each age.

As we have illustrated throughout this work, this same narrative structure appears again in the formation of the Christian Bible. It is a compilation of older tales - stories of former ages - refashioned into a sequence of episodes designed to convey theological doctrine in the guise of history. Yet this process did not begin with the Church. The tendency to rework myth for political and priestly ends was already visible in Egypt itself. By the time the Westcar tales were copied, the age of powerful temple hierarchies had long begun, and the line between revelation and persuasion was no longer clear. Whether the authors of such tales sought merely to instruct or to manipulate is difficult to prove, but the signs of calculated narrative shaping are present. The Westcar Papyrus thus stands not only as the prototype of the world’s sacred storytelling, but also as an early example of how myth could be used - consciously or otherwise - to consolidate belief and authority.

This appendix examines that lineage through one clear lens. It focuses on the parallels between the Westcar narrative and the modern myth of Star Wars, in which the archetypes of Egypt re-emerge almost intact: the living pillar, the hidden field, the father and son, the eternal struggle between order and chaos. Westcar’s tale of yore becomes a ‘once upon a time’, tale, now rendered as ‘In a galaxy far, far away.’ (The Romeo and Juliet current - the hieros gamos of divided lovers - we address elsewhere.) Here we follow instead the return of the Djedi: the living measure reborn in contemporary myth, carrying forward the same geometry of light, proportion, and rebirth that first took form beside the Nile.

Interestingly, not only are the globally familiar archetypes of our own era foreshadowed within the Westcar Papyrus - in figures recognisable today as the proto-Star Wars characters - but so too is another modern icon: Medjed, the ghostly figure that has become a cult symbol in contemporary Japanese art and animation. His veiled form, reimagined across millennia, is now celebrated by the same youth culture that absorbs its mythic heritage through screens rather than temple walls. The persistence of this image reminds us that the past continually re-emerges within the present, as though demanding recognition and restoration. Myth does not die; it transforms, carrying its ancient signal forward until its meaning is again perceived.

Introduction – The Westcar Papyrus and its Setting

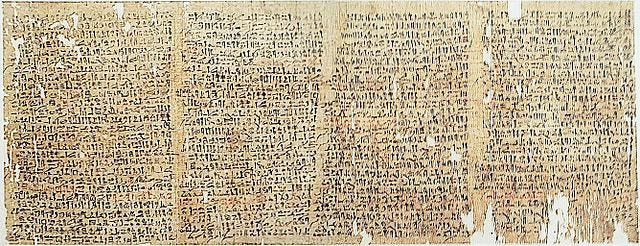

Among the surviving Egyptian texts, few are as revealing as the Westcar Papyrus (P. Berlin 3033). Copied in hieratic during the Second Intermediate Period, around 1600 BCE, it preserves a cycle of wonder-stories set a thousand years earlier in the court of Pharaoh Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid. The manuscript was discovered in fragments in the nineteenth century and named after its first European owner, Henry Westcar.

The work is not a royal chronicle but a sequence of tales told by Khufu’s sons and courtiers to entertain the king. Each episode recounts an act of marvellous skill or divine intervention performed by a wise man or priest. The final story - by far the most important - introduces an aged magician called Djedi, said to be 110 years old, who possesses the secret of restoring life and who alone knows the ‘number of the hidden chambers of the sanctuary of Thoth.’ Summoned before Khufu, Djedi performs feats of restoration and animal control, yet refuses to reveal the measure itself, declaring that the mystery will belong instead to three unborn sons of a priestess at Heliopolis. Those children, he foretells, will become the first kings of a new dynasty.

Intended, it is claimed, to distinguish the Westcar Djedi from a historical prince of the same name, some translators render the magician’s name as Dedi. Yet the supposed need for this distinction is itself suspicious. The Westcar narrative places its Djedi in a story whose principal figure is the uncle of the historical prince, whose grandfather was another significant pyramid building pharaoh - Sneferu - suggesting that the two were never meant to be separated. The overlap hints that the tale preserves genuine ancestral memory veiled in mythic form - a blending of the historical and the archetypal that typifies Egyptian storytelling. To divide the magician from the prince is to miss the point: the text deliberately conflates the living man with the archetype of wisdom, the Djed incarnate in human form. The history of Egypt from Khufu is the beginning of a national religion overseen and inherited by Khufu’s successors.

To modern Egyptology the papyrus is prized as one of the earliest examples of narrative prose, but its deeper value lies in what it records of Egypt’s shifting worldview. Beneath its storytelling surface runs a coded account of a real historical transition: the passing of cosmic authority from the pyramid-builders of the Fourth Dynasty to the solar priesthood of the Fifth. In that sense it is the earliest written reflection on the problem that defines all subsequent religion - the movement of living knowledge from natural science and kingship into institution and doctrine.

For the present study, Westcar is far more than a curiosity of ancient literature. It is a miniature of the entire Egyptian cosmology reduced to parable form, preserving in character and image the essential elements of the Djed - the pillar of stability - and its living counterpart, the Djedi. Through this single tale we glimpse how myth begins: a record of real principles translated into story, carried forward as a vessel of proportion and renewal.

Part 1 – The Hidden Chamber of Light

The Westcar tale sits where the pyramid horizon becomes a saga. In the papyrus, the king Khufu seeks the ‘number of the secret chambers of Thoth’ so that he may fashion his horizon upon that measure. He summons an aged wonder-worker named Djedi, famed for restoration and uncanny control over life-signs, who answers not with a count but with a place: a flint box in a sanctuary at Heliopolis that contains the archive of the measure. The tale closes by deferring actual opening to three unborn sons of a priestess – a dynastic and priestly succession that transfers custody of the measure from the king’s immediate will to a priestly lineage. This is the narrative kernel through which the Old Kingdom’s lived science of proportion becomes transmitted forward in myth.

Read as typology rather than anecdote, the Westcar episode names three functional poles that recur across Egyptian cosmology and later cultural re-workings:

Khufu – the axis of form; the sovereign who wishes to embody the horizon and fix the measure in stone. His undertaking represents the moment when natural observation and artisanal knowledge are elaborated into monumental form.

Djedi – the living Djed; the sage whose competence is resurrection, repair, and custodianship of secret measure. He embodies the operative skill of initiation – what the initiates called Hu and Sia, the sounding and seeing operations of field-work. The story intends Djedi as exemplar of restraint: he knows how, but not when it is right for the knowledge to be used.

Medjed – the veiled field-form; the hidden axis within the chamber, the active principle that animates measure. In our reconstruction Medjed is not an agent of wrath but the living wick and toroidal field that quickens form into life. As such he is the interior principle of Khufu’s sealed architecture: the unseen that permits visible order to function.

This threefold is the simple grammar: form seeks measure – measure is stewarded by living skill – living skill points to a hidden field. The Westcar tale preserves that grammar in story-form. The enigmatic flint box at Heliopolis, at the centre of Djedi’s tale, is not a mere box of curiosities but a mnemonic device: an archive of measure to be opened only by proper succession. The narrative therefore encodes two linked lessons. First, knowledge of measure is a custodial function that requires initiation and social placement. Second, the hidden field is real and must be respected: the rightness of a measure is revealed in a context of alignment, not possession. This is about masonry as a practical art and craft, and Masonry as an initiatic cult.

We have shown that the Egyptians at a very early stage, along with the Mesopotamians, were highly advanced mathematicians who encoded ratio within their works, especially their architecture. The Pythagorean ratios, phi, and the 3–4–5 triangles appear throughout the Great Pyramid’s design. The King’s Chamber is a bare room containing only the ‘sarcophagus.’ Astonishingly, the coffer can be used as a unit of measure to fill the chamber in a 6 × 5 arrangement, producing a seventh row of half-sarcophagi. The resulting volume of the whole structure equals 137.5 units of sarcophagi and partial sarcophagi. That number is remarkable, for 137.5 degrees is the circle’s golden angle - the complement of phi that governs the spirals of shells, plants, galaxies, and the orbital resonance of electrons. The chamber therefore embodies the golden ratio itself - the junction of form and flow, stone and air, Isis and Osiris. Within the sarcophagus the volume of air equals the volume of stone: half solid, half void, half form and half fluid. This corresponds exactly to the axial complete form revealed through our reconstruction, where Isis represents fluid and breath and Osiris represents form.

Whether the finer alignments identified by modern analysts such as Alan Green were consciously calculated at the design stage or arose naturally from the geometry of the pyramid form remains uncertain. It is difficult to imagine such pre-planned precision with the tools of the age, yet the deliberate use of simpler harmonic proportions - such as the 3-4-5 triangle and the carefully angled internal shafts - was entirely within the capability of the builders. The deeper ratios that later appear to approximate constants like 137 or φ are more likely inherent consequences of those basic harmonics than deliberate encodings. What matters is that subsequent generations recognised and revered these underlying patterns: by the time of the Djedi tale, Egyptian initiates already viewed the Great Pyramid as a divine instrument of measure, the “flint box” embodying the sacred number and the laws of creation. Later cultures, from the Pythagoreans to the Elizabethans, continued to echo the same geometric harmonies in their own symbolic and literary forms.

It is therefore reasonable to assume that Djedi (and possibly the historical Prince Djedi) - the miracle-performing magician - was an initiate of the Masonic-priestly guild and that the King’s Chamber of Khufu, and by extension the Great Pyramid itself, is the true subject of the Westcar tale. The sarcophagus is the ‘flint box’ that holds the mysteries. Egyptian initiatory science included Pythagorean mathematics and ratio thousands of years before the historical Pythagoras, whose name was later given to what was already ancient knowledge. The Veil of Isis is the invisible hidden nature of the goddess as phi – the ratio behind the measure, the me of the Djed or Medjed. The field was thus known, measured, and embodied.

The same initiatory ratios resurface in later literature. Shakespeare’s First Folio of Sonnets encodes the same geometrical proportions in its frontispiece and within the poems, matching the dimensions of the Great Pyramid. Alan Green – pianist, composer, author, and Shakespeare scholar – has demonstrated these correspondences in his research on the Shakespearean codes and their relation to the pyramid.

Sonnet 17 contains the following lines:

Who will believe my verse in time to come

If it were filled with your most high deserts?

Though yet, heaven knows, it is but as a tomb

Which hides your life and shows not half your parts.

If I could write the beauty of your eyes

And in fresh numbers number all your graces,

The age to come would say ‘This poet lies;

Such heavenly touches ne’er touched earthly faces.’

So should my papers, yellowed with their age,

Be scorned, like old men of less truth than tongue,

And your true rights be termed a poet’s rage.

And stretchèd miter of an antique song.

But were some child of yours alive that time,

You should live twice - in it and in my rhyme.

Here we find Isis hidden – she who conceals life, the essence of the goddess, and ‘shows not half.’ Only form is seen; the ratio, the air, remains unseen. Isis veiled and hidden in number. The ‘beauty of your eyes’ invokes Medjed – the Wadjet eye of serpent-wisdom, a manifestation of Isis or Sophia. ‘Your true rights’ alludes to the Masonic plumb and square, the rightness of structure in accord with Ma’at, the perfect angle of balance - like the right angled mitre joint. Even ‘a poet’s rage’ conceals a cipher: an anagram of Pythagoras in the mythic sense, the Great Architect Ptah – Peta-goras. (See Appendix I for the PT hydronyms, including Peter, the later ecclesiastical invention of the ‘rock,’ and Appendix VI – Moses as Osiris – for the identity of Shakespeare.)

All of which refer to a document written on papers ‘yellowed with age’; a perfect description of an ancient papyrus document.

These patterns do not stand alone. The same structure of concealment and restoration appears in Book of the Dead Chapter 17, the Djedi narrative, and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 17 - three expressions of one Atumist-Osirian grammar. In Chapter 17 the speaker proclaims, ‘I am Atum when he was alone,’ declaring self-generation from the waters of Nun. The god breathes, names himself, and re-members his own body. Every repetition of the chapter’s formula re-creates that act: knowledge and utterance (Hu and Sia) restore life through measure. The accompanying plume of Ma’at and the atef-mitre of Osiris show that balance and speech are one process - the breath of truth given form.

The Westcar magician Djedi enacts this principle in miniature. His demonstrations of beheading and restoration are not parlour tricks but dramatizations of the same myth. The goose and bull are Osiris’s dismembered body made whole by the word of power. Djedi’s refusal to repeat the act upon a man preserves the sanctity of divine resurrection: it belongs to the god within the pyramid, not to the stage of men. His name, Djed-i - ‘I am the Djed’ - announces his role as the living pillar through which utterance becomes renewal.

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 17 is a Renaissance restatement of this identical grammar in poetic form. Its ‘tomb which hides your life and shows not half your parts’ echoes the sarcophagus of Osiris: the visible half stone, the unseen half breath. The ‘beauty of your eyes’ recalls the Wadjet-Medjed current of sight and emission in the Chapter 17 Book of the Dead , while ‘your true rights’ invokes the plumb and square of Ma’at. Each line equates proportion with truth. The sonnet therefore functions as an English Book of the Dead, using measured verse in place of ritual formula to reveal the hidden life within number.

Across all three sources - the funerary text, the magician’s tale, and the Elizabethan poem - the same elements recur: the voice that restores, the severed head re-joined, the plume or mitre of measure, the coffer or tomb that conceals life, and the knowledge that transforms concealment into illumination. Whether carved in hieroglyph, spoken in the court of Khufu, or written in iambic line, the theme is identical: light concealed within form, released through the right word, and re-united with its source. This is the enduring Atumist logic - creation as utterance, resurrection as alignment, the eternal breath of Hu moving through every language of the ages.

It is the Atumist Memphite mythos that recurs throughout the Star Wars Saga.

The Right Hand of Atum

It is Anakin, not Luke, who first loses his right hand. His right arm is severed at the elbow in Attack of the Clones during his duel with Dooku. The wound carries immense archetypal weight. In Egyptian theology, the right hand of Atum was the instrument of creation, the feminine and receptive half through which the god brought forth life. Atum was self-generated, containing both genders within himself, and creation issued from the union of his being with his own hand. Later priestly redactions demonised that act, turning the creative right hand into a symbol of transgression, thereby suppressing the feminine side of the divine.

An echo of this survives in the ancient Arabian legend of Hubal, said to have had his right hand broken off and replaced with a golden one. The image preserves the same mystery in altered form: the wounded creative limb of Atum restored in consecrated metal - the solar element of perfection and incorruptibility. In Attack of the Clones, Anakin receives an identical restoration: a mechanical golden hand, gleaming like Hubal’s, replacing the lost creative appendage. The film thus replays the ancient myth precisely: the demiurge wounded through pride, losing his generative balance, yet granted a radiant prosthesis that marks both his power and his separation from nature. His golden hand is the sign of his fall into mechanised divinity - the father encased in metal, the Atumic light trapped in dark form.

Luke’s later loss of his own hand in The Empire Strikes Back continues the pattern in narrative rather than ritual form. The prosthesis he receives is made to appear natural, because within the story he must go on living as a man, not as a machine. Yet even that realism serves the symbolism: the lifelike hand completes what the golden one began. Where the father’s metal hand signified separation from the organic and the fall into mechanised divinity, the son’s restored flesh-like hand shows the return of balance - the divine reconciled with the human. The pattern holds without needing conscious design by the filmmakers; the archetype works through the logic of the story itself.

The circle closes with the name Yoda itself. In Hebrew the letter Yod signifies the hand - the creative point from which all letters, and therefore all words, begin. It is the spark of manifestation, the smallest mark yet the seed of the entire alphabet. By naming the living master Yoda, the saga unconsciously invokes this archetype of the restored hand. Yoda is the hand made whole - the fullness of Atum regained after the severance of the creative limb. As the teacher who unites wisdom and power, he embodies the reconciliation of word and deed, of god and goddess, of voice and motion. The ‘hand’ and the ‘breath’ become one operation again: the living Word through which the Force - Hu - is spoken and directed.

Thus Yoda in Star Wars is a direct parallel to the wise initiate Djedi. The resemblance is far more than coincidence: both are elder masters who guard the living knowledge of the field when the old order has fallen into corruption. Each speaks in riddles and inversions, the syntax of initiation that conceals truth from the unready while revealing it to the attuned. Djedi is the archetype of the living Djed - the voice of measure and resurrection - and Yoda fulfils the same function as the last surviving Jedi master, keeper of the balance of the Force. Through him the ancient current reappears in modern myth: the sage who preserves the Word, the breath, and the measure until the age is ready to raise the pillar once more.

The Shafts as Gateways of the Breath

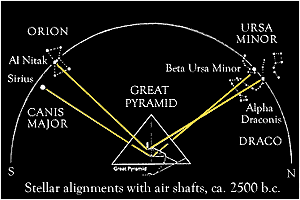

The two narrow channels that leave the King’s Chamber have long puzzled archaeologists. Cut with the same precision as the outer masonry yet too small for human use, they begin at the level of the sarcophagus and rise through the mass of the pyramid at carefully calculated inclinations. Their purpose cannot be practical ventilation: they were sealed at both ends and would have required extraordinary labour to create if mere airflow were intended. Their geometry and orientation show that they are symbolic and astronomical in design – gateways for the king’s spirit, or breath, to ascend to the heavens.

Each chamber of the Great Pyramid possesses such channels, but only those of the King’s Chamber pierce the outer casing and open to the sky. The lower Queen’s Chamber shafts stop short within the masonry, suggesting an unfinished or ritual function. The King’s Chamber pair, however, are precise instruments of alignment. When measured in 19th- and 20th-century surveys – Petrie, Edgar Brothers, Badawy, and later Rudolf Gantenbrink’s robotic exploration in the 1990s – the data proved exact.

The southern shaft departs the chamber’s southern wall at roughly 45° and emerges on the pyramid’s 50th course. In the epoch of 2550 BCE this line of sight intersected Alnitak (ζ Orionis), the easternmost star of Orion’s Belt, when it culminated on the meridian. Alnitak was the star that ancient texts identify with Sah, the celestial Osiris. To the Egyptians this was the point of rebirth: the star through which the soul of the justified king ascended to join the body of the god. The southern shaft therefore formed the literal breath-path of Osiris – the conduit by which the king’s spirit, warmed by the life-heat of the ritual chamber, rose as living breath toward the constellation of resurrection. The hidden essence of Isis, the queen of heaven.

The northern shaft leaves the wall at about 32° 36′ and aimed, in the same period, directly toward Thuban (α Draconis), then the Pole Star. Thuban marked the pivot of the heavens, the imperishable axis around which the constellations turned. Egyptian texts called these northern stars the Ikhemu-Sek, the ‘Unwearying Ones,’ eternal lights that never set. The king was said to ‘join the circumpolar stars and never die.’ The northern shaft thus symbolised the fixed Djed – the eternal stability of the soul.

Together the two channels define a perfect duality: motion and rest, resurrection and eternity, breath and axis. The king, lying within the coffer – the flint box of Thoth – becomes the Osirian body. His final breath rises through the southern passage as the Hu of Atum, a form of Isis, the living voice ascending toward her mate in Orion. The northern passage anchors that ascent in permanence, linking the same soul to the unchanging stars of the circumpolar sky. The structure therefore reproduces in stone the entire Osirian mystery of death and rebirth, uniting heaven’s dynamic and static poles.

Thermodynamic studies support this interpretation. Even with modern measuring devices, a faint convection current persists within the shafts; warm air from the chamber rises through the southern conduit, cooler air descends from the north. The pyramid literally breathes. The architects appear to have designed the monument to embody the same motion that its symbolism proclaimed – the alternation of inhalation and exhalation between earth and sky. The upward flow of heated air is the physical manifestation of the breath of Hu; the downward draw through the northern duct is the returning whisper of Ma’at, restoring balance. The life drawn from the sun’s heat of the day by the cold of the night. Horus journey’s through the cycle and returns to his Father and Mother by convection.

The Polar Gate of the North

If the southern shaft of the King’s Chamber directed the breath of Hu towards the belt of Orion and thus to Osiris, its northern counterpart carried an equal weight of symbolism. It opened not toward the sun’s path but to the eternal axis of heaven, the point about which all stars revolved. Through this narrow duct the king’s spirit was to ascend into the region of the ‘Unwearying Ones’ - the imperishable stars that never set.

When Khufu’s pyramid was raised, the star that occupied that position was Thuban (α Draconis) in the constellation Draco. Around 2550 BCE Thuban lay within a third of a degree of the true celestial pole, making it the still eye of the northern sky. To the Egyptian astronomer-priests this was the immovable pivot, the celestial Djed, the visible emblem of Ma’at’s stability. The northern shaft of the King’s Chamber, inclined at about 32° 36′, was calculated with remarkable accuracy to aim directly at Thuban when it culminated on the meridian. In that epoch the star would have appeared each night at the same point above the horizon, circling minutely but never setting - a perfect image of eternal life.

The texts of the Pyramid Age confirm this doctrine. In the Pyramid Texts of Unas, the king ascends ‘to the sky among the stars that know not destruction.’ These were the Ikhemu-Sek, the Unwearying or Imperishable Ones, the same circumpolar lights to which the shaft was directed. Through that narrow channel the breath of the pharaoh was believed to join the unchanging northern realm, ensuring that his soul would never die.

But as the centuries passed, the heavens themselves drifted. Because of Earth’s slow axial precession - a motion completing one cycle in about 25,800 years - the celestial pole traces a vast circle through the stars. Between Khufu’s time and the composition of the Book of the Dead more than a thousand years later, the pole had moved several degrees away from Thuban and toward the group of stars we now call Ursa Major and Ursa Minor - the Plough or Great Bear. By the early New Kingdom (c. 1500 BCE) Thuban no longer held its station; the stars of the Plough had become the practical guide to north, circling closest to the true pole.

This astronomical shift is clearly reflected in later Egyptian texts. In Book of the Dead Chapter 17 and related passages, the celestial pole is described not as the serpent of Draco but as the Bull’s Thigh - the constellation known to us as the Plough or Ursa Major. The myth recounts that the thigh of the celestial bull (Set) was torn from his body and fixed in the northern sky by Isis, forming the new imperishable constellation. The goddess thus re-established order in the heavens after the slaying of Osiris. What for the Old Kingdom was Thuban’s fixed star became, by the New Kingdom, the Plough - the visible emblem of the same immutable axis. The mythology adapted to the changing sky without losing its meaning.

The continuity is unmistakable. Both Thuban and the Bull’s Thigh mark the pole of the world, the still point around which the cosmos revolves. The Egyptian priesthood simply translated the axis from one constellation to another as precession demanded. The theological content remained constant: the northern gate as the realm of eternity, the southern gate as the path of resurrection. The pyramid’s alignment is therefore the architectural expression of a truth that the later texts verbalised - the dual nature of ascent. Through the southern shaft the breath of Hu rose as living utterance toward Orion, uniting with Osiris; through the northern shaft the same breath entered the realm of the undying stars, achieving permanence. Motion and stillness, form and field, the twin currents of Isis and Osiris, were perfectly balanced.

The precision of the pyramid builders’ design is confirmed by modern astronomy. Computer reconstructions of the sky at 2550 BCE show that the northern shaft aimed at Thuban within less than one degree of error; the southern shaft, at the same date, at Alnitak in Orion’s Belt. No later monument reproduces this level of stellar exactitude. The Great Pyramid thus encodes the heavens of its epoch - the Osirian sky of Thuban - while the Book of the Dead preserves the theology of its successors - the Isian sky of the Plough. Between them lies the sweep of precession, yet the axis remains unbroken.

Symbolically, this shifting of the polar guide mirrors the very process of death and rebirth that the pyramid itself enacts. The pole moves, yet the centre endures. Thuban yields to the Plough as Osiris yields to Horus: the new star carries forward the same light. In this way the architecture, the myth, and the motion of the heavens all speak the same language - the breath of the world moving through the body of time. The northern shaft is the gateway of spirit, the mouth of the pyramid through which the eternal air returns to the stars.

A note on the dismissals of the alignment theories: some writers ascribe the pyramid’s stellar geometry to a much earlier date, while others reject all such theories for lack of exactitude. To both positions it must be said that we are not dealing with modern surveying, but with symbolic alignment - a correspondence of meaning rather than mechanical precision. Within the tolerances achievable by Fourth Dynasty techniques, the data remain consistent and compelling. The pyramid’s design was intended to mirror the heavens, not to satisfy the standards of modern engineering. The fact that its orientations still register within a degree of their intended targets after forty-five centuries is evidence enough of deliberate purpose. To dismiss the alignments because they do not fit either conventional chronology or speculative catastrophism is to overlook the symbolic accuracy that the Egyptians themselves prized most: harmony between sky and stone, between the motion of the stars and the breath of the world.

The Foreleg of the Bull and the Vengeance Cycle

In the northern sky the Bull’s Thigh - the foreleg of the celestial bull - became, by the New Kingdom, the chief emblem of the pole. The Egyptians called it Mesketiu the ‘ham’ or foreleg; in one Egyptian myth Thoth cut off one of Set’s legs and hurled it there. (In Mesopotamian myth it was hurled there by Enki.) The constellation we now call the Plough, Big Dipper or Ursa Major. The myth describes the punishment of the slayer: Set, the murderer of Osiris, immobilised and pinned to the polar axis so that he could do no further harm. Each night the unchanging stars marked his eternal binding.

This same motif of dismemberment, vengeance, and restoration runs like a hidden thread through Western drama. Shakespeare inherits it consciously in Hamlet. The prince’s very name conceals the Ham, the foreleg of the bull, and his story recapitulates the Osirian cycle in human form. The murdered father is Osiris; the usurping uncle, Claudius, is Set - uncle of Horus; the grieving and divided mother, Gertrude, the Isis–Nephthys figure who embodies both loyalty and error. Hamlet’s vengeance is not personal but archetypal: the restoration of cosmic order through exposure of the hidden crime. ‘The play’s the thing wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king’ is the formula of initiation - the use of enacted truth to compel confession and rebalance the field. The duel and mutual death that end the tragedy are the Western echo of the same myth that the Book of the Dead resolved in the judgement hall: wrong must consume itself so that Ma’at may stand.

The pattern repeats once more in the modern mythos of Star Wars. Darth Vader - his very title an echo of Djedi and of father - enacts the Setian role. As Anakin he is the luminous son, the Horus yet to fall; as Vader he becomes the dark twin who destroys the maternal principle. His ‘slaughter of the innocents’ in the temple mirrors the Exodus tale of Moses, the Herodian massacre of the biblical redaction and the Setian outrage against Isis and the child Horus. The archetype recurs with perfect fidelity: the old order turned to violence against the seed of renewal, the mother or guardian spiriting the infant to safety. Luke, like Moses, is concealed on the desert’s edge, raised by foster parents until his destined time. Both grow to manhood unaware of their true lineage, called at last by a voice from the unseen world - be it the burning bush or the spectral Obi-Wan - to deliver their people from bondage. The cycle is clear: the mother dies or is defiled, the son descends into shadow, and through the compassion of his own offspring the axis is restored. Luke, the Sky-Walker, completes the work of Horus by redeeming the father; the hidden light returns to balance.

Thus the Ham of the northern sky, the Hamlet of Renaissance theatre, and the Jedi–Skywalker/Vader of modern cinema are different tellings of one continuum - the vengeance of light against the destroyer of form, the restoration of the goddess’s place within the field. From the Bull’s Thigh to Elsinore to the Death Star, the same symbolic geometry persists: the severed limb fixed in heaven, the guilty brother unmasked, the son who reconciles heaven and earth. All are chapters of the same Osirian–Atumist scripture, retold in the languages of their age.

No other explanation fits so completely both the geometry and the theology. The pyramid is a mechanical hieroglyph of respiration and resurrection. Its form is the Djed; its interior motion, Medjed. The King’s Chamber is the heart of this living structure, half stone and half air, half body and half breath. Within it Isis, the fluid spirit, meets Osiris, the perfected form. The southern shaft is her out-breath, the ascent of life towards the stars of Orion; the northern shaft is his in-breath, the eternal return of order from the circumpolar realm. The king, typically sealed within the sarcophagus, thus becomes the point of equilibrium between the two – the living axis through which the universe renews itself.

Later cultures preserved faint memories of this celestial engineering. Biblical references to Jacob’s ladder reaching unto heaven and to the trumpet of God that shall raise the dead echo the same concept of a vertical conduit between worlds. In the Pyramid Texts of Pepi II, Atum is described as ‘binding a rope ladder for the king,’ by which the soul ascends to unite with the Creator. The ascent takes place between the two lions of the horizon - the twin guardians of sunrise and sunset that mark the eternal doorway of rebirth. The pyramid’s shaft was the physical expression of that ladder, the ‘voice’ of the monument - a column of invisible energy linking the earthly chamber to the stars, precisely as the Westcar story described: the hidden chamber of Thoth whose measure opens only to the initiated.

From a purely scientific standpoint, the alignments are exact enough that coincidence can be ruled out. Precession of the equinoxes has since altered the sky, but computer reconstructions of 2500 BCE confirm the shaft to Alnitak and to Thuban within less than a degree of accuracy. The builders therefore designed the Great Pyramid as a stellar instrument – a monument that breathes and speaks, expressing in architecture what the priests expressed in liturgy: the ascent of the spirit through the measured harmony of light and air.

Textual and material echoes reinforce this reading. Khufu’s Horus name Medjedu, as documented in the chapter material, situates the king himself as a functionary of the hidden axis – an embodied Djed who renders measure visible in the built horizon. The later Medjed of the Book of the Dead, far from being a curiosity, is the cultural memory of that operative: a veiled form with radiant eyes and toroidal presence, described in funerary texts as an agent of renewal and continuity. Conventional readings have miscast Medjed through a single gloss; this reconstruction restores him to his true axial, vesical, and wick-like nature.

Architecturally, the ‘secret chambers’ motif maps to a broader Egyptian practice: inner sancta that are timed and opened by right sequence. The Pyramid Texts and Unas’s funerary inscriptions show an identical concern with interior speech and sealed measures - the king reciting the words of ascent, the text functioning as procedure rather than poem. The Westcar story therefore preserves a second-order memory of that procedure: that which is sung or said at the right node effects a change in relation to the field. In practical terms, the tale teaches restraint - the keeper of the measure reveals its locus, but nominates the proper heirs rather than simply transferring control to royal desire.

Viewed in the light of my IXOS architecture, Medjed functions as the enclosed attractor - the toroidal return within which line, circle and spiral find coherent recursion. The flint box at Heliopolis is therefore symbolic shorthand for a resonant manifold: a contained geometry that will only answer to an initiated sequence of operations. The Westcar narration thus encodes a proto-physics of custodial alignment - the idea that measure and field interact only when proper operator, place and lineage coincide. This is the technical moral of the story: mastery without initiation becomes spectacle; initiation without right measure becomes dogma. The tale preserves both warnings.

The Medjed–Djedi Axis: The Measure of Giza and Heliopolis

Reassessing the Name and its Context

Egyptology has long followed Faulkner’s tentative gloss of Medjed as “the smiter.” The artificially broken term mdj (from me-djed) however also means to set firm or to establish. When read through architectural language it refers to fixing a pillar, not striking.

In the titulary Khufu Medjedu, the suffix –u denotes embodiment: “he in whom the axis stands.” The name therefore describes Khufu as the established one – the living Djed, the human embodiment of Ma’at and the operator of measure.

Djedi, Medjedu and the Migration of the Axis

In the Westcar Papyrus the magician Djedi knows “the number of the chambers of the sanctuary of Thoth.” This is a cipher for geometric measure – the hidden ratio that defines both temple and cosmos. Djedi, the knower of measure, mirrors Medjedu, the establisher of measure.

When the royal cult moved from Saqqara to Giza, and later to Iunu (Heliopolis), the same axis moved with it. Medjed – the pillar of measure – literally “walked.” Heliopolis was not a new creation but a rotation of the original geometry: Giza reborn in solar alignment. The tale instructs initiates – to understand Iunu, study the perfected axis at Giza.

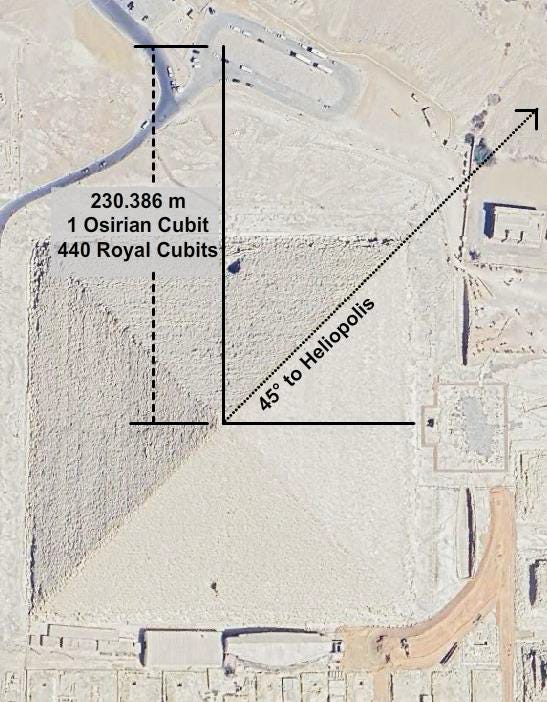

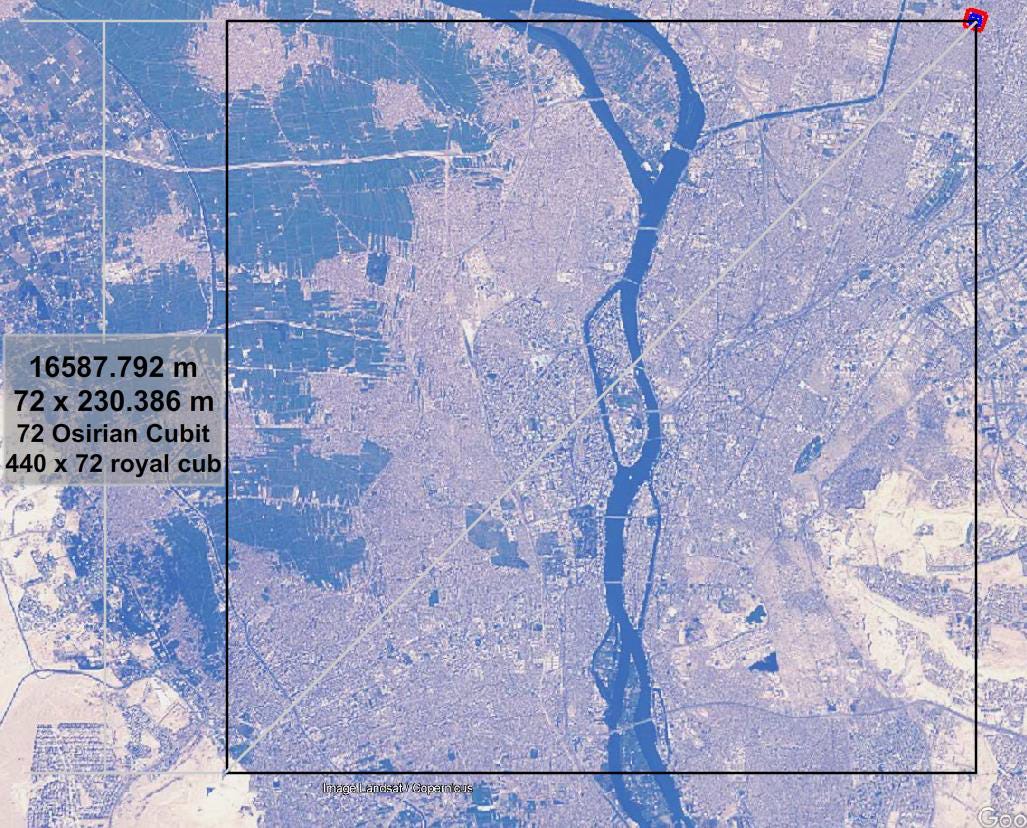

The Geometry of Transmission

Carl Balowski’s 2024 metrological study confirms that the line from the Great Pyramid to Heliopolis lies at 45 degrees to the pyramid’s base. The right angle unites the square of Earth with the circle of the Sun – a physical expression of the Djed in motion.

He identifies an “Osirian Cubit” equal to one-seventy-second of the Giza-Heliopolis square, encoding the solar year’s 72 divisions and the Osiris cycle. The same 72-based system appears in the 5:6 relation between the megalithic yard and the metre, linking Neolithic, Mesopotamian, and Egyptian measure in one field geometry.

Empirical Summary

• Giza base to Heliopolis alignment – 45° (1:√2) – Earth–Sun right angle, migration of the axis

• “Osirian Cubit” to Giza base – 1:72 – solar year division, Osiris cycle

• Megalithic yard to metre – 5:6 – Drift-culture scaling constant

• Royal Cubit – 0.523 m ≈ π/6 – circle ratio embedded in linear unit

Together these ratios form a coherent harmonic system linking terrestrial and celestial geometry. They are measurable facts, not speculation.

From Balowski (2024) and related surveys:

Satellite mapping shows the Giza–Heliopolis axis (45°) continuing beyond Cairo, intersecting the modern suburb of Matariya, identified with ancient Iunu.

The measured distance between the Great Pyramid and the Heliopolis temple mound is approximately 23 km, forming a 1:100 ratio to the pyramid’s base, another scaling harmonic.

The temple of Re-Atum at Heliopolis faces 90° to the Giza alignment, preserving the same orthogonal schema.

The Osirian Cubit (3.2053 m) appears as a modular unit in later Nilotic surveying inscriptions, linking it to the Royal Cubit (0.523 m) by a clean factor of six.

Together these observations reinforce that Heliopolis was geometrically and ritually derived from Giza, not invented anew.

(Images from The Great Pyramid of Heliopolis - AN OSIRIAN CALENDRIC UNIT FROM KHUFU’S PYRAMID USED FOR LARGE SCALE - METROLOGY (LSM) Carl Balowski | April 2024)

Interpretation

Medjed names the state of established balance. Djedi is the fictional practitioner of that balance, and the priestly scribe who transmits this knowledge through his fable. Medjedu is the embodiment of that balance in the king. Khufu Medjedu therefore stands as the archetypal Axis-King, operator of Ma’at and measure. When the cult centre moved eastward the axis was not abandoned but transplanted – Iunu became Giza rotated toward the rising sun. The myth records the geometry.

Significance

Recognising Medjed as the principle of established measure restores a lost cornerstone of Egyptian science. It integrates language, myth and metrology within one system of proportion. The new data confirms that Egypt’s sacred architecture was an extension of Neolithic field geometry – a Drift-Culture inheritance spanning thousands of miles and centuries (see Chapter 6 for further evidence of the shared measure and geometry across continents). Medjed, long mistaken for a minor “smiter,” emerges as the keystone of Ma’at itself – stability through proportion, the living Djed of the world axis.

From the Axis to the Perfection of Measure

The geometry embodied in the Medjed–Djedi axis opens directly into the broader Egyptian fascination with how form rises from foundation. Their myth and architecture revolve around the act of raising the triangle from the base, the visible birth of height and spirit from the square of matter. The same act reconciles the triangle, square, and circle – the three primal forms through which every ratio of nature is expressed.

This was no poetic conceit. The Egyptians were working within the same harmonic constants that science now quantifies. The ratios governing the pyramid’s slope, the sun’s apparent motion, and the cycle of precession are the same ratios that describe light’s behaviour and temporal dilation in modern physics. What the Egyptians called Ma’at – truth through balance – is the same structural equilibrium that sustains the physical universe.

The ten-point circle and tetractys ratios derived in the IXOS framework demonstrate mathematically what the ancient builders perceived intuitively: that the universe is recursive, harmonic, and self-similar at every scale. The square is matter, the circle is motion, and the triangle is the mediating field that allows one to become the other. When Khufu raised the Great Pyramid, he inscribed that law in stone – the harmonic that modern science has only recently rediscovered as relativity’s geometric constant.

The Egyptian system, in its purity, was therefore a scientific philosophy as well as a sacred art. It united observation and revelation in a single act of measure, foreseeing within its own geometry the harmonic relationships that physics now recognises as universal law. (See Appendix XII - The Perfection of Measure - for a thorough examination of this data).

The King’s Chamber: The Geometry of the Axis

Following the Medjed–Djedi alignment between Giza and Heliopolis, the geometry of measure finds its purest expression inside the Great Pyramid itself. The King’s Chamber is not simply an interior room – it is a fixed model of the harmonic field. Carl Balowski’s metrological study (2024) demonstrates that this chamber embodies the same constants of ratio found throughout the Egyptian canon and across the earlier Drift-Culture field geometry.

The Chamber as a Harmonic Field

The plan of the King’s Chamber is a perfect 2:1 rectangle – a doubled square. The short wall measures ten royal cubits, the long wall twenty. Using the verified royal cubit of 0.523606 m, the chamber’s width is 5.236 m, its length 10.472 m.

The diagonal across the floor is √5 times the short side:

5.236 × √5 = 11.708 m.

The ideal height, formed by halving the diagonal, is √5 ÷ 2 × 10 = 11.18 cubits – a value confirmed within Petrie’s recorded range. Thus, the chamber completes the sequence of the two simplest harmonic fields:

Square to diagonal = √2 → the royal cubit relation.

Rectangle (2:1) to diagonal = √5 → the golden field relation.

The pyramid’s internal geometry therefore mirrors the same harmonic logic as the Giza–Heliopolis axis: a rotation from the square (Earth) to the diagonal (Heaven).

The Right Triangle of Measure

In his paper The Geometrical Trifecta: The √5 Right Triangle, the King’s Chamber, and the Potential Metric Legacy of the Royal Cubit, Balowski identifies a special case of the 1:2:√5 triangle that locks perfectly to the King’s Chamber dimensions. If the short side is taken as 3 + √5, then:

short = 5.236 m

long = 10.472 m

diagonal = 11.708 m

This single triangle produces an extraordinary equality:

area = perimeter = (3 + √5)² = 27.4164

In other words, the triangle balances its own measure – its surface and boundary are numerically identical. This is the literal manifestation of Ma’at: area and perimeter in perfect harmony.

Verification of the Unit

The cubit value used for these calculations is not speculative. It is the midpoint of Petrie’s and Dash’s independent surveys of Giza:

Petrie (1883): mean implied cubit = 0.523701 m.

Dash (2015): mean implied cubit = 0.523563 m.

Balowski’s working value of 0.523606 m lies directly between them. The same figure is confirmed by physical artefacts:

Rod of Maya = 0.523 m (−0.12%).

Rod of Kha = 0.524 m (+0.08%).

Across three millennia the royal cubit remains within a single millimetre of its Old Kingdom value – proof that it was not an arbitrary unit, but a product of geometric law.

The Chamber as a Living Equation

When drawn as a plan, the King’s Chamber expresses the simplest progression of form:

A square (1:1) becomes its diagonal (√2).

The square doubled into a rectangle (2:1) becomes its diagonal (√5).

Half the diagonal (√5 ÷ 2) gives the height, creating a perfect spatial harmonic.

In symbolic language: Earth (square) → Heaven (circle) → Axis (triangle).

Every major element of the pyramid follows the same law: the base defines the square, the height embodies the diagonal, and the apex joins the two through the triangle of transformation. The King’s Chamber is the geometric heart of that transformation.

The Djedi Principle Made Stone

In the Westcar Papyrus, Djedi “knows the number of the chambers of the sanctuary of Thoth.” The King’s Chamber is that sanctuary made manifest – the chamber of measure. Its proportions contain the number that unites all right-angled forms.

The name Djedi thus encodes knowledge of the 2:1 field – the passage from the square of matter to the triangle of ascent. It is the living Djed, the fixed axis around which light, sound, and time unfold.

When viewed through this lens, Khufu’s pyramid is not a tomb but an instrument of proportion, an architectural theorem that translates the hidden ratios of nature into visible form.

Summary of Empirical Data

• Chamber plan – 10 × 20 royal cubits (5.236 × 10.472 m).

• Floor diagonal – √5 × 10 cubits = 11.708 m.

• Ideal height – √5 ÷ 2 × 10 cubits = 11.18 cubits.

• Working cubit – 0.523606 m (midpoint of Petrie and Dash).

• Triangle identity – 1:2:√5 → area = perimeter = (3 + √5)².

• Rods of Maya and Kha confirm cubit stability within 0.1%.

Meaning within the Axis

The King’s Chamber confirms that the geometry of Giza was not decorative, but structural – a direct embodiment of the same measure that connected Medjed (the fixed axis) with Djedi (the knowing of measure). The chamber is Ma’at realised in stone: a right-angled world reconciled through proportion.

It stands as the silent proof that the Egyptian canon was grounded in measurable, harmonic constants. These same ratios run through the Drift-Culture monuments, the Near Eastern rods of measure, and the golden fields of later temples.

Through Khufu Medjedu, the Djed became flesh; through the King’s Chamber, the Djed became form.

By accident or by design?

It seems beyond doubt that the Orion alignment was deliberate, confirming the Storm God thesis that the monument was designed as a living reflection of the sky whose primary focus was Orion at night. Yet it is less certain that the pyramid builders consciously employed all the Pythagorean and phi-based mathematics that later generations discerned in its form. The pyramid’s many complex harmonic proportions may have arisen organically, the natural outcome of empirical technique guided by observation of the heavens and the Nile’s geometry. Simple tools - plumb line, cord, and sighting staff - applied with precision and intuition could have produced the relationships we now call sacred geometry.

By the time of the Westcar tale, however, much more may have been observed and understood. The priests and sages who preserved the Pyramid tradition could see that the structure embodied mathematical perfection, even if its earliest designers had intuited rather than calculated it. In that recognition the pyramid gained a second life as a text of number - a monument that seemed to encode the laws of creation itself. Legends backed by geometry became irrefutable; myth gained the authority of measure. From this perception grew the later cults of initiation centred on Giza, and eventually the Sphinx cult, in which the pyramid and its guardian were no longer seen as tomb and statue but as the axis of cosmic knowledge, a geometry made divine.

Finally, politically the Westcar episode marks a real transition. The tale is set in Khufu’s court yet the revelation belongs to heirs of a priestess at Heliopolis - an allegory of the transfer of cosmic custody from monumental kingship to the solar priesthood that will shape the Fifth Dynasty. In other words, Westcar is not merely a parable about magic; it is a memorialisation of a structural shift in custodianship of the axis. That shift is precisely the pattern Chapter 10 traces: the living science of Ma’at becoming a managed theology of institutional priests. The Djedi tale remembers the moment when knowledge moved from embodied king to initiated cleric - and when the hidden axis continued, disguised as ritual.

The axiom is worth repeating here:

Myth + Math = Ma’at

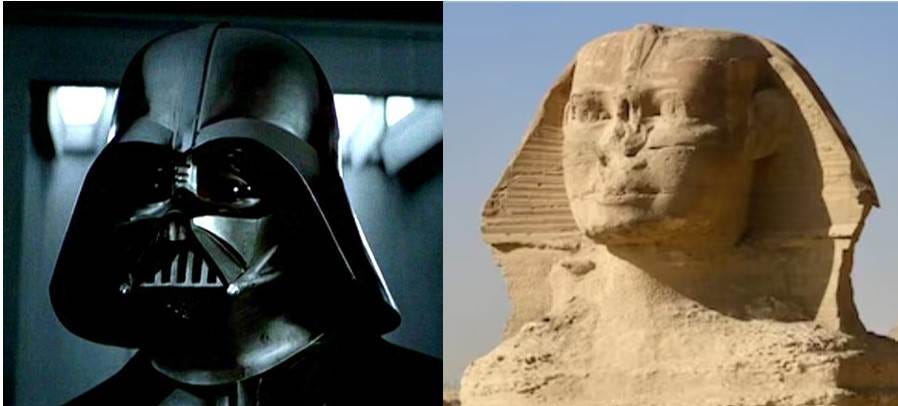

The Sphinx and the Father of Terror

At Giza the cycle finds its first and last image in the Sphinx, the silent guardian of the horizon. In Egyptian it was known as nḥ3-ḥr - literally ‘the Face of Terror.’ The phrase denoted not cruelty but awe: the visage of overwhelming power that confronts the soul at the threshold of the divine. To meet that gaze was to face the unknown, the very force that could unmake or renew creation. In later Arabic the same being was called Abū al-Hawl, ‘the Father of Terror,’ a title preserving both the fear and reverence the monument inspired.

The Greeks translated the name simply as Sphinx - ‘the strangler’ - emphasising its aspect as the trial that tests those who seek knowledge. Across all tongues the meaning endures: the terrifying beauty of the divine face, the stillness before revelation. Vader’s first terrible act as Jedi/Sith (a clear reference to Seth) black magician is to strangle his naysayer who mocks the ways of the Force. In the Death Star’s conference chamber, Admiral Motti derides Vader’s reliance on the Force to recover the stolen plans, boasting instead of the station’s mechanical power. Motti’s arrogance about the Death Star’s invincibility and his contempt for Vader’s ‘sorcerer’s ways’ provoke the unseen response of the ancient archetype: the Force choke, as Vader declares with icy precision, ‘I find your lack of faith disturbing.’ It is the Sphinx’s ordeal reborn - the strangler confronting hubris, compelling silence before the mystery of unseen power.

In form and in essence the Sphinx anticipates the modern image of Darth Vader, whose name itself means ‘Father.’ He is the Father of Terror, the living Abū al-Hawl of our era. The sculpted nemes headdress becomes the black helmet; the serpent crest becomes the angular ridge of the visor; the serene royal countenance becomes the mask of dread. The angular mask is the pharaoh’s disfigured face. When Anakin is burned and sealed within the armour, his transfiguration mirrors the priestly mutilation of the Sphinx - turning the living nḥ3-ḥr, the Face of Light, into a petrified emblem of fear. Both figures are monuments to the captured breath. Vader’s mechanical respiration - the slow, rhythmic exhalation that defines him - is the distorted echo of Hu, the creative utterance reduced to machine sound. His voice fills the darkened temple of the cinema as the Sphinx’s silent breath once filled the dawn horizon.

The Beheaded and the Hidden Box

In the Westcar Papyrus, Djedi demonstrates his mastery by beheading and restoring a goose and a bull. To Egyptologists this has long seemed a display of priestly magic, yet its logic is deeper. It is a hieroglyphic allegory, a coded reference to the place of the hidden measure. The tale is nominally set at Iunu (Heliopolis), but its imagery points unmistakably to Giza - the true site of the ‘Head of Terror,’ the Great Sphinx. The act of beheading and reunion signals a topographical and symbolic key: the ‘flint box’ of Thoth lies not in the solar temple of Heliopolis but beneath the gaze of the Sphinx, where the living head of the god meets the chamber of sacred number.

The Sphinx itself is a colossal decapitated head - a human face rising from the body of a lion. Carved from a single ridge of limestone, the head is geologically distinct from the body, its scale reduced and re-cut in antiquity. Ancient accounts described it as the ‘Face of Terror,’ nḥ3-ḥr, a severed or ‘cut’ face, the guardian at the threshold of knowledge. In later Arabic this became Abū al-Hawl, the Father of Terror, preserving both awe and dread. The monument is therefore the petrified emblem of the very ritual enacted by Djedi: the separation of head and body, intellect and form, and their re-union through the word of power.

The goose restored by Djedi is another cipher for the site itself. The bird was sacred to Geb and Amun and to the Benben - the mound of first creation. Its Egyptian name, ges or g’s, is phonetically close to Giza. The ‘restored goose’ is thus the restored Giza, the reborn mound of creation. When the magician re-attaches the head of the bird, he is re-membering the benben - the original mound whose apex became the pyramid and whose guardian was the Sphinx. The story tells us, in mythic shorthand, that the box of measure is concealed at the place of the goose, the place of the head - Geesa, the Giza plateau.

This association continues seamlessly into the visual language of modern myth. Darth Vader’s head and helmet - always emphasised in silhouette and ritual framing - are the mechanical counterpart of the same archetype. The Sphinx’s mutilated face, the ‘Head of Terror,’ finds its echo in Vader’s black mask and resonant breathing. Both are fallen suns encased in darkness, guardians of a mystery whose resolution comes only through revelation of the hidden face. When the mask is removed, the terror dissolves and breath returns to its natural rhythm. The decapitated head is re-joined to the body, the Djed raised, the field restored.

Thus, the beheading motif of the Westcar tale is more than allegory; it is a cartographic and symbolic code. It identifies Giza as the locus of the ‘flint box,’ uniting the Sphinx, the benben goose, and the head-restoration rite in one continuous act of initiation. The ‘Face of Terror’ at Giza and the ‘head restored by word of power’ in the papyrus are one and the same event - the awakening of the conscious axis through the breath of the field. The site, the myth, and the modern vision all converge upon the same revelation: the head of stone speaks again when breath and measure are reunited.

The same Djedi code surfaces again in Sonnet 17, where the poet laments that his ‘verse in time to come’ will not be believed, ‘though yet, heaven knows, it is but as a tomb which hides your life and shows not half your parts.’ The ‘most high deserts’ are not merely virtues or rewards but the literal deserts that for centuries buried the Sphinx to its neck. The monument was indeed ‘a tomb which hides life,’ its body entombed in sand while only the head - the Face of Terror - remained visible. The sonnet thus describes the Sphinx’s condition: a living form turned sepulchre, its hidden geometry and sacred measure concealed beneath the ‘high deserts’ of time. The line ‘shows not half your parts’ speaks with uncanny precision of the monument’s half-buried state. The poem therefore preserves, in Elizabethan cipher, the same knowledge held in the Westcar tale - the riddle of the severed head and the hidden body, the tomb that hides life, and the promise that one day the buried truth will be uncovered and the full form revealed once more.

The parallel is exact. The Sphinx stands before the pyramid as guardian of initiation; Vader stands at the threshold of the saga as guardian of the shadow. The ‘Father of Terror’ is the same archetype refracted through time: the disfigured light awaiting redemption, the silence before the return of the word. When the mask is finally removed and the human face revealed, the breath becomes natural again, and the old terror dissolves into recognition. In that instant the nḥ3-ḥr of Giza breathes once more - the petrified god restored through understanding.

Thus, the Face of Terror, whether carved in limestone or cast in metal, remains one figure: the fallen sun behind the veil. Its redemption through light and breath is the Return of the Djedi itself - the awakening of the living field from the sleep of stone, the Father of Terror transformed back into the Father of Light.

Part 2 – From Horizon to Screen: Rebirth of the Sky-Walker

The Westcar Papyrus marks the first fully preserved moment in human literature where sacred narrative turns consciously mythic, using story to transmit an inherited science of nature. When Khufu seeks the secret number of Thoth’s chambers, he is not chasing superstition but the geometry of creation itself – the correspondence between heaven and form. That same quest, written in a different language, still plays across our cinema screens. The modern audience that watches a spacecraft rise toward twin suns is being invited into the same horizon that Khufu built in stone.

The horizon was always more than a line. In Egyptian it was Akhet – the junction of sky and earth, a glyph formed by a sun disc rising between two hills. Every temple and pyramid was an architectural expression of that symbol. Each morning, as the sun emerged between the cliffs of the eastern bank, the world renewed its covenant with light. The king stood at that point of emergence, the living mediator between heaven and earth. When Khufu named his pyramid Akhet-Khufu – ‘the Horizon of Khufu’ – he identified himself with the moment of rebirth itself. The monument was both tomb and sunrise, the fixed axis through which the solar field re-entered the world.

It is this archetype that survives intact in the image that opens Star Wars: the small moon of Tatooine, the twin suns, and a young man gazing toward the horizon. Luke Skywalker’s name is itself a translation of Heru-Shemsu-Pet, ‘the sky-walker’ – the Horus-figure who traverses the heavens, bridging the mortal and the divine. His journey is not invention but revival. The desert world, the twin lights, the unseen father, and the call to restore balance all replay the oldest Egyptian mythic cycle – the emergence of Horus from the hidden Osiris to re-establish Ma’at. The audience recognises it instinctively because it is the same psychic structure that has moved through the human imagination since the Pyramid Age.

The desert of Tatooine mirrors the arid plateau of Giza. The domed dwellings recall the ancient mastabas, half buried in sand. The twin suns echo the dual aspects of the solar god – the day-sun Re and the night-sun Atum – whose eternal alternation sustains creation. The mechanical moisture farmers who draw vapour from the air repeat the ritual logic of the Egyptian temple, where water from the Nile was lifted to refresh the god each dawn. Even the robots – tireless servants of order – are modern personifications of the Shabti, the animated helpers placed in tombs to serve the resurrected soul. What seems futuristic is a full circle back to the ancient: the same symbolic grammar expressed through new materials.

Within this frame, the Westcar story functions as the mythic prototype. Khufu’s longing to reach the secret of the chambers is the same yearning that drives Luke to leave his homestead. Both seek the hidden principle of renewal. Djedi, the sage who holds the knowledge but withholds its use, becomes the model for the elder guide – Obi-Wan Kenobi – whose wisdom lies in restraint. In both tales the younger hero must earn revelation through ordeal, not command it by will. The lesson is identical: true power arises from alignment with the field, not from domination over it.

The Akhet – the horizon – is thus the stage upon which the archetype repeats. In Egypt it was the physical junction of sky and land; in the modern myth it becomes the boundary between worlds, the threshold to space. When the spacecraft rises beyond the planet’s curve, it crosses the same symbolic gate that the soul crossed in the Pyramid Texts. In both cases, the act is resurrection – the ascent of the luminous body from the tomb of matter into the living field. What for Khufu was the Great Pyramid’s internal geometry becomes, for the filmmaker, the geometry of light projected through the cinema lens.

This is why the Star Wars saga resonates globally in a way few modern stories do. Beneath its technological surface, it restores the oldest sacred narrative known to humankind: the passage from darkness to light, from ignorance to insight, from imbalance to Ma’at. The cinema has become the new temple of illumination, the screen a modern Akhet through which light is born from shadow. The audience, seated in darkness, experiences the same ritual sequence once enacted in the inner chambers of Egyptian sanctuaries – descent into obscurity, revelation through radiance, and return to the world transformed.

The Westcar tale anticipated this entire cycle. By transferring the secret from the king to the unborn heirs of a priestess, it foretold the periodic renewal of knowledge itself. Each age must recover the measure in its own idiom. The priesthood of Heliopolis inherited it through the Fifth Dynasty; the philosophers of Greece recast it in geometry; the theologians of Rome encased it in creed; and the storytellers of our own time rediscovered it as mythic cinema. The horizon remains the same; only the language of its light changes.

In this sense the Star Wars epic is the natural re-emergence of a pattern long imprinted in human consciousness: the solar ascent, the filial succession, the return of the balance of the Force – which is simply the return of Ma’at. The sage who vanishes into light, the father who falls into shadow, and the son who restores the unity of opposites are Egyptian in every detail. They belong to the same cosmology that once defined kingship, measured pyramids, and shaped the earliest literature. The Westcar Papyrus, the Great Pyramid, and the modern screen are stages of a single continuum – the story of light seeking itself.

Part 3 – Djedi, Djed, and Medjed: Pillar, Sage, and Field

To read the Westcar story properly, one must see that its three principal names - Khufu, Djedi, and the unspoken Medjedu principle implied through Khufu’s Horus name - describe not separate individuals but functions of a single process. The king, the sage, and the hidden field together embody the triune structure through which Egypt expressed every act of creation: form, measure, and life.

The Djed was the oldest of these forms. In temple reliefs it appears as a pillar with four crossbars, a stylised spine representing the stability of Osiris, the god who dismembered himself into matter and was re-raised through love and order. To ‘raise the Djed’ was both ritual and equation: to align the axis of the body, the pillar of the temple, and the spine of the cosmos. Each level mirrored the others. The act was repeated annually in the festival of Khoiak, when the priests hoisted a great wooden Djed before the assembled people - a symbolic reinstatement of coherence after the flooding of the Nile and the disarray of the year’s death.

The Djedi of Westcar is that pillar made sentient. His very name carries the verb djed - to say, to declare, to endure - followed by the personal particle i, ‘I am.’ ‘I am the Djed’ is thus his title and his nature. The feats he performs before Khufu are demonstrations of Osirian power in living form: the restoration of a severed head to its body, the calming of lions, the pronouncement of hidden measure. These are not tricks of magic but statements of mastery over the field - the same powers that the Pyramid Texts ascribe to the resurrected king. Djedi is the living Djed: the master of articulation, whose utterance (Hu) and sight (Sia) align word, breath, and light. When he declines to reveal Thoth’s secret, he acts according to the higher rule of Ma’at - knowledge withheld until harmony allows it to be received.

Beneath both stands the Medjed principle, rarely named but everywhere present. In the Westcar papyrus his figure appears as a rounded, veiled form with two eyes or beams of light issuing outward. He is a raised benben or bread sign. Earlier scholarship misread the accompanying captions as ‘he who strikes from the eye,’ but in this study, following the re-examination we recognise the phrase not as violence but as description: the emission of life-force through vision, the outward radiation of awareness. Medjed is the Djed in motion, the field within the pillar - the toroidal flow that sustains form. His covering cloth marks latency; his eyes are the points of emergence where energy meets perception. He is the invisible medium that gives life to structure, just as the wick gives life to flame.

Khufu’s own Horus name, Medjedu, confirms the link. It denotes ‘the hidden Djed’ or ‘the concealed measure’ - the same concept encoded architecturally in the sealed chambers of his pyramid. The image of Medjed on the greenfield Papyrus specifically depicts him next to the goose and in the air is the falcon - one representing the earthy ensouled and the falcon the other aspect of the duality of the ba bird, as the soul that rises to Heaven after death. Within that geometry the living field was thought to circulate eternally, preserving the king’s Ka within the currents of light. The Egyptians saw the earth reflected in the heavens, which was the basis of the afterlife journey. As above, so below. As in life, so in death.

In this way the three figures - Khufu, Djedi, Medjed - compose a single archetypal sequence: the form that seeks balance, the master who knows balance, and the field that enacts balance. Balance which includes a judgement after death, typified by the weighing of the heart against the feather of Ma’at. All is dualist and cyclic to the Egyptian initiate.

This triad recurs throughout Egyptian religion. In the body it appears as spine, breath, and pulse; in architecture as base, pillar, and capstone; in language as noun, verb, and meaning. The Djed is stability; Djedi is consciousness of stability; Medjed is the living field that makes stability possible. Together they describe the mechanics of resurrection. When the Djed is raised, Djedi’s word animates it, and Medjed’s unseen motion sustains it. The dead god rises because the field within him still turns.

The symbolic actions in the Westcar narrative match this inner science. When Djedi re-joins the head and body of the goose and ox, he performs the Osirian act of reintegration - the reconciliation of above and below, intellect and matter. When he calms the lions, he harmonises the solar and chthonic forces that define the Egyptian cosmos. His knowledge of the number of the chambers signifies not arithmetic but the awareness of proportion: how many divisions of light are required for the world to remain coherent. Yet he does not disclose them to Khufu, for the king represents manifested order; the mystery must pass to a new house where interpretation, not construction, will rule. Thus the priesthood of Heliopolis is foretold.

This is the moment when Egyptian cosmology changes phase. What had been enacted through stone and ceremony now becomes transmitted through word and text. The Djed, once raised in physical rite, becomes a written glyph; Djedi’s utterance becomes the formula of priests; Medjed’s living field retreats into image and symbol. The Westcar Papyrus records that shift in parabolic form - the movement from direct communion with the field to its management through ritual mediation. The priestly sons born of the Heliopolitan woman are not merely new kings; they are custodians of a new order in which the field will be controlled by words rather than by works.

In the long drift of time, this internal transformation reappears wherever civilisation moves from craft to clerisy. Each epoch retells it in its own idiom. The modern world repeats it in technological myth, where the living axis returns as the Force and its keepers are once again called Djedi. Their powers of restoration, restraint, and perception are the same. They embody the union of Djed and Medjed - the axis and its unseen flow - re-expressed in a culture that builds with light instead of limestone.

Thus the Westcar tale, when read beside the figure of Medjed and the architecture of Giza, yields a complete grammar of renewal. The Djed is the law of form; Djedi is its conscious articulation; Medjed is the field that carries it forward through every retelling. Together they form the living pillar of civilisation - a structure that rises, falls, and is raised again whenever humanity remembers that the measure of the world lies not in power but in alignment.

The axis, the Djed, is stability itself, yet it is shown with legs and feet to signify motion - the ability of the cosmic pillar to walk, to shift its ground from one horizon to another. When the spiritual centre moved from Giza to Heliopolis, the axis could be said to have to ‘walked’; the priests of the sun carried the measure eastward and made a new cult centre for the same light. Medjed is a mobile mound with legs and feet. Yet the tale of Djedi restores the true axis, reminding us that the foundation does not truly move - the living measure endures beneath the sand, awaiting rediscovery. Giza and the Great Pyramid was the original axis.

Djedi’s speech is deliberately enigmatic. He speaks in code and metaphor, employing the language of cipher used by the ancient philosophers: riddling statements that reveal themselves only to those who know the pattern. His manner of expression is the ancestor of initiatory syntax, later echoed in the seemingly inverted speech of Yoda, the sage of Star Wars, who also ‘speaks backward’ so that wisdom may be heard only by those who listen beyond the surface. Both use reversal as a teaching device - the turning of language upon itself to awaken perception, the living echo of the Djed’s own balance between stability and motion.

The portable axis and the biblical echo

What the Bible relates two millennia later is a fictionalised memory of Egypt. The cult axis - symbolised by Medjed - was moved to new centres and each time a temple was raised to the same grammar of measure. The axis walked. The geometry stayed.

In the Hebrew retelling the god is carried in a box called the ark of the covenant. A tribe of initiates move with it from camp to camp until a new axis is fixed at Jerusalem. There Solomon plays the Khufu role - the axis-king who founds the house on archetypal lines.

The Bible is not history in this respect. It is an appropriated recollection of Egyptian culture - a portable axis recast as a portable chest.

Every temple since has repeated the pattern. Inner sanctum on the measure. Outer courts set to the same ratios. Later churches keep the axis by raising a spire or tower - a stone djed - to mark the spine of place.

This typology was formulated under Djoser at Saqqara, perfected at Giza under Khufu Medjedu, and then taught in initiatic code. The Djedi tale preserves the craft knowledge as story. A thousand years later the same memory is reflected in biblical tales of priests carrying the ark and settling at Jerusalem, where the new axis was laid.

One spine. Many names. The measure does not change.

The Axis in Motion – R2-D2 and C-3PO

In the visual language of Star Wars, the archetypes of Egypt appear translated into technology. R2-D2 functions as a mobile axis, a living benben. His compact, cylindrical form is strikingly similar to early images of Medjed - the veiled, pillar-like being whose presence represents unseen motion and hidden agency. R2-D2 is therefore the axis in motion, carrying the thread of the narrative through every generation of the Skywalkers. Lucas originally conceived him as the narrator of the saga, making him the Djed of the tale - the enduring structure through which memory is transmitted.

The name itself encodes the archetype. R2 can be read phonetically as Ar-Tor or Artu, directly aligned with Arthur or Ar-Tor - the ‘high hill’ or ‘axis of the world’ central to this study. In Latin American Spanish, R2-D2 is affectionately called ‘Arturito,’ meaning ‘Little Arthur,’ an unconscious return to that same root. The following character, the Greek Δ (delta), signifies the raised triangle or pyramid, resonant with the archetypal form of the benben. The full name R2-D2 thus reads symbolically as Ar-Tor Delta2 - the small, mobile twin axis of balance and restoration.

Within the story, R2-D2 embodies this function. He is the keeper of codes and keys, the one who restores communication and reactivates systems - precisely the operational role of the living Djed. This echoes the codes and keys implied as the cipher behind Djedi’s role in the Westcar tale. The tale which implies that the axis moved to Heliopolis, but should be looked for at Giza.

R2 is also, at times, a literal smiter (even though the word is falsely derived), echoing the contested interpretation of Medjed as a 'striker” or “projector’ of force. Where the ancient figure was said by Faulkner to “strike from the eye,” R2-D2’s discharge - or electric arc - takes mechanical form: an electrical prod or taser used to stun and repel. These scenes present the ancient function recast through machinery: the pillar as conductor of current, the energy of the field focused into visible discharge.

Beside him stands C-3PO, his golden counterpart - the reflective complement to R2-D2’s silver-blue. In Return of the Jedi, C-3PO is literally worshipped as a god, the articulate emissary of protocol and order. Together they represent the two metals of harmony - gold and silver, the phi and delta whose interplay generates the geometry of the pyramid. They are the comic yet archetypal dyad of proportion: the radiant and the hidden halves of the cosmic axis, through which the Force - the living field - remains in balance.

The Golden God

Gold held a sacred and immutable place in Egyptian cosmology. It was the flesh of the gods, the visible sign of the imperishable and the solar. Texts from the Old Kingdom onwards describe the deities as being made of nbw, pure gold, while the bones of the gods were silver and their hair lapis lazuli. Because gold does not tarnish or corrode, it was regarded as the perfect material expression of immortality and divine radiance. The living king was ‘the Golden Horus,’ the solar embodiment of vitality and power, his body a reflection of the undying sun. The pharaoh’s regalia, from the death mask of Tutankhamun to the gilded sceptres and coffins of the New Kingdom, expressed this doctrine materially: gold was the sun made tangible, eternal life made visible.

In this archetypal role C-3PO mirrors the golden god of Egypt. His entire form is burnished metal, his speech precise, ceremonial, and rule-bound. When he is hailed as a deity by the Ewoks in Return of the Jedi, the scene reproduces an ancient image: the polished figure of order, eloquence, and etiquette worshipped as the sun-faced intermediary between heaven and earth. He is the linguistic and luminous half of the pair - a master of the word - a Hu-Bal, lord of breath, therefore is analogous to Atum - the golden manifestation of proportion and law, set beside R2-D2’s hidden, silvery axis. Together they embody the same polarity encoded in Egyptian thought: gold as the immutable solar essence, silver as the reflective lunar field - the two metals whose union defines the geometry of balance and the perfection of the pyramid.

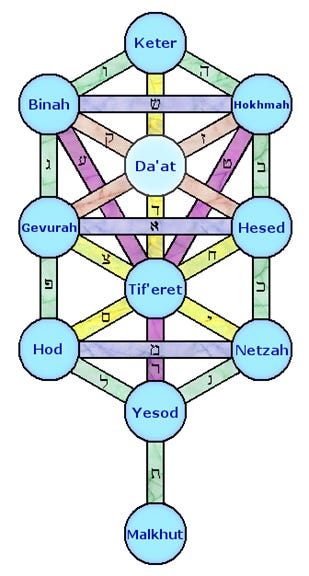

Darth as Daat

The meaning of Daat in the Kabbalistic system is significant, and the figure of Darth Vader is clearly drawn from this archetypal interpretation of the Hebrew Bible. However, the Hebrew root itself is derived from the Egyptian, as the evidence shows.