Return of the Storm God - Chapter 3

Rise of the Storm God

Introduction - The Sky Was Their First Scripture

Long before temples were built or gods were named, there was the sky.

Wherever early humans lived - across mountains, plains, islands, or deserts - they looked up. Night after night, they observed a consistent field of lights moving overhead. No instruction was needed. No ritual was required. The sky was not a theory. It was simply there.

In environments without artificial lighting, this experience is difficult to ignore. The night sky dominates. It presents structure, contrast, and movement. Stars appear in number. Patterns repeat. Some shift over the course of hours. Others return year after year.

For modern observers, that experience still exists - but only in places removed from urban light. In such conditions, the night sky takes on an intensity that is rarely encountered in contemporary settings. It demands attention. It invites interpretation.

For early humans, this was likely a central frame of reference. The contrast between day and night was not only physical, but cognitive. Day was a time of action. Night introduced a different domain - quieter, ordered by stars, less predictable in its events. Lightning, wind, and weather emerged under it. So did memory.

To engage seriously with ancient culture is to begin by attempting to see as they saw. Not through myth, faith, or science - but through the direct experience of the visible sky. This is where structured observation likely began.

What could be seen?

· The daily rising and setting of the sun.

· The changing phases of the moon.

· And the movement of stars - fixed in their relationships, but wheeling in rhythm.

Among these patterns, three stood out more than others:

The arc of the sun, returning each day.

The recurring shape of the moon.

And in winter, a particular figure: a symmetrical formation now called Orion.

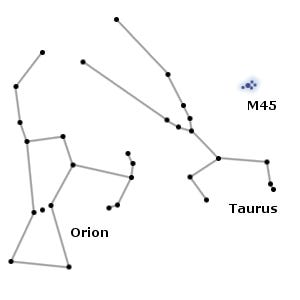

Image 1 - Orion over the peak.

Of all the visible constellations, Orion is one of the most distinctive. Its features are clear and easily recognized by eye: three stars in a row form its belt, with two bright stars above - the shoulders - and two more below. To most observers, it appears upright, directional, and humanoid. It faces toward the region of Taurus, the Bull, and beyond that, the cluster known as the Pleiades.

It is the most visually imposing and immediately recognizable stellar formation visible to the naked eye. Its presence is seasonal, returning when the days are shortest - and when symbolic thinking, in many cultures, turns to death, rebirth, and return.

It is not necessary to imagine whether early humans noticed this figure. We can be certain they did - because it is still there. It remains fixed. It continues to draw the eye.

So we begin not with interpretation, but with observation. Not with theory, but with attention.

If you can access a dark sky, do so. Let your eyes adjust.

Look up.

See what they saw. And feel what they must have felt: an all-encompassing sea of darkness speckled with a myriad of points of light. Let your imagination run with that for a while - to become that early one, encountering this phenomenon. Try not to intellectualise the experience at first. Let it unfold organically.

Remember, early humans had no formal physics or learned framework to explain this. Their understanding was shaped by direct experience and cultural memory. Let that stay with you. And feel, if only briefly, how your own mind aligns with the emotions and impact it must have brought. Only then are you qualified to understand what this book is really about.

Joining the Dots

Once Orion is seen, it is not easily forgotten. Its structure imprints itself.

But the recognition of a form raises another question: what else can be found, depending on how one connects the points?

This is not symbolic invention. It is a matter of geometry and perception. The stars are fixed. The lines are ours to draw.

Try it.

· Connect the centre of the belt to the head and feet – a cross.

· Trace the arc of the sword – it may resemble a fishing line, or a phallic extension.

· Frame the shoulders and lower stars – a vessel, a throne, a gate.

· Curve that frame, and you may see a boat. Or a fish.

· Mark the open space between the legs – a doorway, or the impression of descent.

· Extend a line from the raised arm to the foot – a club, a hammer, a branch.

· Look forward to the V-shaped formation of Taurus – a beast, or a fixed target.

· And beyond that, the compact cluster of the Pleiades – the seven stars, often interpreted as sisters, watchers, or scattered sparks.

The belt of Orion also points directly toward a brilliant, flickering star low in the sky – Sirius. Positioned behind and below, it may suggest a companion, a hound, a messenger, or a spirit in flight. In this extended sightline, the belt becomes more than geometry. It becomes a path.

What else can be recognised?

Here are some of the forms that may emerge - not as fixed meanings, but as visual possibilities, shaped by alignment and repetition:

A boat

A cross

A club

A staff

A shepherd’s crook

A flail

A sceptre

A hammer

A torch

A spear

A bow and arrow

A thrown weapon

A slingshot

A fish

A bull-hunter

A wound or point of impact

A cradle

A coffin

A throne

A gate

A triangle

A circle

An anchor

A watcher

A giant

At this stage, no symbolic assignments are made. No deity is defined.

We begin, as early observers did, with the visual field alone.

From that field, patterns arise. From those patterns, memory begins. And from memory, association.

This is the process - not starting from a written myth, but from what is seen. The sky did not change. The names did.

We are not concerned yet with what those names became. We return instead to what was visible - before it was spoken.

Now follow Orion’s direction of gaze: He faces a shape - less symmetrical than his own, but no less persistent in the visual memory of the sky.

A crooked V of stars, with a bright red point near the centre - this is the formation we now call Taurus, the Bull.

To earlier observers, it may have appeared as a horn, a wedge, a beast, an open mouth, or a threshold. Its form is distinct, and its placement directly opposite Orion invites comparison.

Just beyond it lies a compact cluster - the Pleiades: Seven stars, tightly grouped, often interpreted as sisters, companions, or messengers. This formation recurs in cultural frameworks across the ancient world - from Anatolia to the Aegean to the Americas - and appears to have held shared significance over a wide temporal and geographic range.

Image 2 - Orion Faces The Bull that Hides Pleiades (By Dumbbell at French Wikipedia - work by fr:Utilisateur:Dumbbell, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1613254)

So the question arises: what configurations were seen?

· A figure facing a beast.

· A challenge.

· A pursuit.

· A boundary.

· A confrontation.

· A form rising toward a horned presence - perhaps in defence, perhaps in threat.

· And beyond the beast, a group of seven - dispersed like birds, or gathered like a hidden cluster.

From this visual arrangement, story structures could easily take root.

Not yet formal myth. Not yet named gods. But recognisable figures: a hunter and a bull, a slayer and a threshold, a man and his test.

Above all of this - not fixed in the stellar field, but moving slowly across it - is Jupiter: bright, consistent, not part of any figure but always passing above and through them.

Jupiter’s motion is not uniform. At times it appears to slow, pause, and reverse direction before resuming its forward path. This reversal is perceptible across weeks, and to regular observers it would have been unmistakable. Jupiter does not behave like the stars. It crosses from horizon to horizon, not as a shape, but as a presence - detached, deliberate, and returning.

It does not speak. It does not intervene. But it sees.

To those who watched the sky, Jupiter may have appeared as the night’s all-seeing eye - surveying the field below, silent and unblinking. Not a figure within the main story, but the one who watches it unfold.

These are not yet the written stories. But they are the conditions from which the stories emerge.

We make no interpretative claim beyond the act of seeing.

The lights are there. The forms appear. The mind connects. The memory follows. This is what the psychology of anthropology shows.

This is how the oldest symbolic systems began - not with a voice, but with a sky full of signs.

The visual configuration described in the preceding section - comprising Orion, Taurus, the Pleiades, and the visible path of Jupiter - forms what we will refer to throughout this book as the Primary Nexus.

This arrangement is not selected arbitrarily. It is based on visibility, repetition, geographic universality, and its recurrence within early mythological frameworks from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean. It is this nexus - stable in the sky but mutable in interpretation - that we now follow into the emergence of the storm god.

The Mountain of Origin: Ararat, Urdhu, and the High Place

The story of the storm god does not begin in temples, nor with names carved in stone. It begins on the ground, beneath a sky that offered itself each night without fail. And it begins on a mountain.

The region today known as the Armenian Highlands, dominated by the unmistakable profile of Mount Ararat, forms the geographic and mythic axis of this study. This is not a symbolic claim but a topographic and observational one. Ararat is the highest, most visible peak in a vast surrounding basin. It appears as twin-peaked, snow-capped, and self-evidently monumental to any observer within hundreds of kilometres. To those who lived in this region from the Palaeolithic forward, this was the point where the earth rose up to meet the sky.

The mountain is named "Ararat" in the biblical tradition, but the deeper historical name is Urartu, and in still earlier renderings, Urdhu. These terms share a linguistic and conceptual lineage. In Akkadian, "Uru" often denotes a city or exalted place, while "Urdhu" connotes height or ascent. The mountain's twin structure likely gave rise to later Mesopotamian references to the "mountain whose name is double" - a phrase that recurs in flood literature and in divine geography alike.

Image 3 - The twin peaks and plain of Ararat in Armenia.

In the Sumerian and Akkadian texts, mountains to the north and east are regularly associated with divine origin, hidden knowledge, or cosmic thresholds. Aratta, the shining kingdom beyond Sumer, often imagined in mountainous terrain, was said to be a source of metals, mystery, and the gifts of civilization. It is almost certainly a memory - or mythic transposition - of this same highland zone. So too with the mount of Nisir, where the ark of Utnapishtim comes to rest in the Epic of Gilgamesh. These mountains are not interchangeable allegories. They are projections of a remembered geography: the high place, the rising axis, the visible seat of the storm.

In Armenian and Hurro-Urartian contexts, this highland tradition is preserved not only in the names of the mountains but in the very function of their gods. The Urartian god Haldi, often associated with war and kingship, was always invoked from the mountain. His temple iconography shows him standing atop a lion or mountain, armed, radiant. Likewise, the Hurrian Teshub is depicted standing upon two mountains, holding a thunderbolt and a weapon, facing the bull. These are not metaphors but sky-rooted icons - reflections of the night sky above the mountains themselves.

To the north and east of Mesopotamia, where the night is clear and the sky deep, the figure of Orion rises in full clarity above the horizon during the winter months. This is the same season in which storms are most likely. Orion’s stance is fixed: upright, wide, with a raised arm, facing toward Taurus. From the vantage point of early peoples living in the Ararat basin, Orion would have appeared above the twin peaks of the mountain in a season marked by thunder, wind, and darkness.

What would they have seen?

A towering figure. A Giant. Arms raised. Facing the beast. Framed by snow and black sky. At the time of greatest vulnerability - in winter - this figure emerged each year to take its place above the mountain. Not a star. A being.

This was not yet a god, but it was something more than light.

And from this mountain, beneath this figure, the oldest story began to form: a storm-bringer, a guardian, a challenger, a being who stood in the sky when the world seemed cold and broken. A prototype. a ‘Proteus’: the shifting form of power and presence yet unnamed.

This is where we begin: not with names or texts or theologies. But with a place - Ararat - and a form - Orion - as they met in the earliest sightlines of the people below.

The Twin Peaks and the Breaking of the Axis

The visual dominance of Ararat in the highland sky is matched by something more abstract but equally vital: the symbolic power of the twin peak. Throughout the myths of the Near East and the highland cultures north of Mesopotamia, the image of a double mountain appears again and again. It is more than a geographic feature - it is a cosmological template.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the hero journeys to Mount Mashu, a place described as having twin peaks that "guard the rising and setting of the sun." In Hurrian myth, the storm god Teshub is depicted standing between two mountains - Namni and Hazzi - understood as guardians of cosmic order. These are not interchangeable motifs, nor literary flourishes. They are reflections of something observed.

From the perspective of those dwelling near Ararat, the mountain presents not a single summit, but a split - Greater Ararat and Lesser Ararat, rising side by side with a saddle-like depression between. The visual symmetry is natural, unmistakable, and resonant. It invites projection: two horns, two guardians, two doors.

The importance of such a form in myth-making cannot be overstated. The twin mountain becomes a gate - the place of threshold. Between them, the sun rises. Through them, stars pass. And above them, in winter, Orion stands.

But we must not reduce this archetype to Ararat alone.

The visual and symbolic structure of the twin peaks appears across multiple traditions. It becomes integrated into the broader mythos of the sun god, who rises in the east and descends in the west - another expression of Nature's fundamental duality. These, too, are twin peaks or pillars: morning and evening, ascent and descent. The axis mundi - revolving around the pole star - later emerges as a vertical twin structure, rising and falling, enshrined in both Biblical and esoteric traditions.

Myth operates through such layers. Archetypes converge, sometimes confusingly, but not arbitrarily. With deeper understanding, we recognise these not as contradictions, but as coexisting forms - totemised, symbolised, and then shaped into myth.

From such a structure, early cultures constructed the idea of the cosmic axis - the vertical alignment between heavens, earth, and underworld. In stable ages, this axis was imagined as fixed, trustworthy, centred. But when calamity came - storm, flood, darkness - it was as though the axis had broken. The order of the world had tilted. The gate had been breached.

This breach is not mere metaphor. In precession and axial wobble, the ancients - even without instruments - would have noticed subtle shifts over generations in where stars rose, in when they returned. Orion's position relative to the mountain and horizon slowly changed. The stars drifted. The heavens turned. For cultures that saw the sky as law, this was not a neutral occurrence. It was a cosmic crisis.

Thus, the flood myths and the tales of gods warring over mountains begin to make internal sense. A deluge may have been remembered in water, but its true origin is astral - a sense of collapse from above. When the heavens break, the storm god rises to contest or restore. And when the peaks are split, it is there - in the gap between - that the figure is framed.

The breaking of the axis becomes a story about who can stand when the world is no longer stable. The storm god, forged in that breach, becomes the one who straddles it - often literally, in iconography, between two peaks.

At Ararat, with Orion rising cleanly between twin mountains, this narrative form was not invented. It was observed. And from that alignment, the mythic architecture of gate, breach, storm, and restoration took shape.

The mountain provided the frame. The sky delivered the crisis. And in that space between - the axis broken - the figure of the Storm God took form.

The Flood and the Ark Before the Boat

The deluge story - so widespread in Western mythology - is most often encountered today as a tale of judgment and survival: rain from above, the earth overwhelmed, a boat of salvation, a remnant preserved. But this familiar rendering, shaped by later Babylonian and biblical redactions, masks something older and more fundamental.

In the earliest strata of Near Eastern cosmology, the flood is not first a meteorological event. It is a celestial one.

From Ararat, and across the highland arc to the east and north of Mesopotamia, the night sky defined the seasons, the sacred, and the stable. Its patterns were considered eternal. So when those patterns shifted - when stars appeared out of season, or the position of known figures moved across generations - it was interpreted not as astronomical drift, but as cosmic disorder. In such a worldview, the flood was not merely water rising, but orientation collapsing. The axis that held the heavens steady had broken.

In this context, the ark does not begin as a boat. The oldest semantic roots for “ark” - in Sumerian, Akkadian, and early Semitic forms - refer to an enclosure, a chest, a box, or a sanctuary. It is a space of preservation, not necessarily a seafaring vessel. The first ark is the mount itself: the place that rises above the flood, the summit that does not drown, the point of reorientation.

In Mesopotamian flood accounts, the ark of Utnapishtim comes to rest not in the south, but on Mount Nisir, a peak to the northeast - in the highland direction of Ararat. Nisir may or may not be Ararat precisely, but the conceptual geography is clear: the flood is world-encompassing, and salvation comes not from watercraft but from ascent.

In the Armenian and Anatolian region, older than Sumer in its habitation, we see carved into high places the imagery of circular or oval enclosures - raised sanctuaries, domed spaces, tholos chambers (round beehive-like chambers). These may represent memory forms of the earliest "arks" - places not to ride out the storm, but to realign when the sky had turned unfamiliar.

Within this structure, the figure of Orion - upright, steady, seasonal - becomes the visual promise of a return to order. When the flood comes (cosmic or earthly), and all familiar forms dissolve, it is he who reappears in the same place each year. His emergence over the horizon is a reassurance, a cosmological anchor. And so, naturally, the stories of survival begin to gravitate around him. He becomes the watcher, the guardian of the ark, the one who “stands” when all else is drowned.

It is only later, once cities, scribes, and ships enter the cultural vocabulary, that the ark becomes a literal boat. And even then, in many tellings, it is square - a box - not a hull. In Hebrew tradition, it becomes the mobile chest that carries the spirit and voice of their god from place to place. The notion of riding the waves is a metaphor applied retroactively to what was once a symbolic refuge - not a craft of navigation.

Thus, from the twin peaks of Ararat, the image is not of a ship launched into chaos, but of a figure rising, framed against the stars, marking the high point that does not submerge. The ark is not under him - it is in him, or through him: a passage back to stability.

The flood was not a punishment. It was the breaking of orientation. And the ark, before it was ever a boat, was the place where the world began again.

At the base of Ararat lies a curious geological formation - a boat-shaped ridge, long noted by both locals and modern researchers. This is the Durupınar site, located approximately 30 km south of the mountain, out on the plains - precisely where shepherds would have grazed their flocks for millennia. Though not a ship, its contours resemble a vessel embedded in stone, as though stranded by a vanished tide. To ancient eyes, the visual echo would have been unmistakable: a great ark, grounded after the flood.

Image 4 - The Durupinar ‘Ark’ on the plains below Ararat.

It is easy to see how such a formation, observed without modern geological knowledge, could have seeded the myth - not through fantasy, but through form. The flood must have risen, they reasoned, if a boat had come to rest so high, and it must have been, to them, a world-encompassing event – a global flood. In this way, the land itself taught the myth.

This may also explain why the flood motif appears long before the Biblical Noah: embedded already in the Babylonian king list, where a deluge divides the reigns of mythic early kings from those who followed. The biblical redactors, writing nearly three millennia later, re-situated the ark and the primal patriarch at Ararat - not as origin, but as reassertion. It was a return of primacy to the mountain, rewritten as if the storm god had descended anew.

But in truth, he had never left.

He had always been there - standing at the summit, written in the stars, remembered by the rivers. Only the myth had drifted: from Turkey to Mesopotamia, and from there to Judea. The ark - as an arc of return, back to where it had always been.

Orion: The Figure Emerges

If the flood marked a rupture - the breaking of cosmic order - and the ark signified a place or pattern of survival, then it is Orion who stands as the earliest form of coherence in that disrupted sky.

From the vantage point of the Armenian Highlands, particularly in the regions surrounding Ararat, the constellation Orion dominates the winter sky. It rises just before dawn in late autumn, fully ascends through winter, and begins to disappear by spring - a seasonal figure associated not with the lushness of growth, but with the austerity of survival. Its timing aligns with the hardest months of the year: cold, dark, storm-ridden.

What early peoples would have seen is this: a pattern of lights, regular, symmetrical, appearing always in the same place at the same season, framed directly above or near the twin peaks of the horizon. The form itself is immediately legible - three stars in a line (the belt), flanked by brighter stars above and below (the shoulders and lower limbs), with a hanging formation below the belt (often called the sword). The whole appears upright, in motion, facing forward - toward the cluster of Taurus and the Pleiades.

Unlike the moon, which changes shape, or the planets, which drift across the sky, Orion appears fixed. It has internal geometry, symmetry, proportion. It does not flicker into abstraction. It declares itself.

This may have been one of the first moments in which early humans saw the earthly form ‘below’ in the sky ‘above’; not as a set of lights, but as a figure. And that figure was not passive. It was wide-armed, striding, weaponized. It stood in opposition to something: Taurus, the Bull - another stellar configuration of weight and momentum.

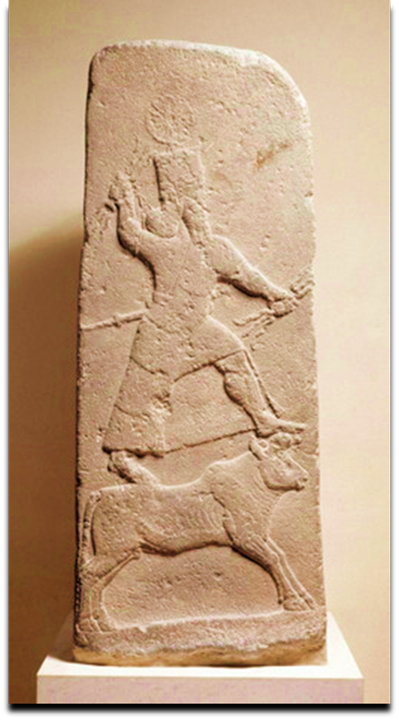

Image 5 - Orion Hunter of the Bull - Slayer of the Beast.

Orion’s emergence marked not only the return of a familiar pattern, but the reassertion of cosmic logic. When the stars had shifted, when the axis seemed broken, and chaos loomed, Orion returned. His posture became a signal: the one who stands, who faces, who holds.

In this way, Orion begins to function as the first prototype of what would become the storm god: not a bringer of chaos, but the figure who rises in its midst. His weapons are not destructive, but symbolic instruments of re-ordering - the club, the sword, the bow, the staff. His posture is not one of rage, but of bearing - aligned, observable, coherent.

Importantly, this figure is not local to any single culture. It is not a product of language or theology. It is a shape in the sky, visible across the Northern Hemisphere, but from Ararat especially - a land of open horizons and clear winter air - its presence is overwhelming.

Orion may not have been named by the earliest watchers, but he was seen. And as we shall explore in the next part, once form is seen, it becomes a template. The storm god emerges not from imagination - but from recognition.

The Emergence of Ishkur

The first storm god to appear in the historical record is not Teshub or Baal or Zeus. It is Ishkur.

Named in the earliest Sumerian and Akkadian sources, Ishkur is the bringer of thunder, lightning, and disruptive rain. He is not a fertility god. He is not a grain deity. He does not bless - he intervenes. His presence is marked by wind, by noise, by violence in the air. He is invoked not for prosperity, but to break drought, punish cities, or cleanse the land.

And seasonally, he arrives with winter - just as Orion rises.

In this way, Ishkur becomes the first cultural articulation of the figure described in the sky throughout the Primary Nexus. The stance of Orion - upright, armed, directional - matches the functional character of Ishkur. He stands when others fall. He brings the storm. He judges. And in his hand is not a gift, but a weapon.

From this archetype, later expressions will follow - Teshub, Haldi, Hadad, Baal, Thor. But it is Ishkur who stands first. And it is through him that the storm becomes a god.

Image 6 - Ishkur/Hadad dominating the Bull with Lightning rods in his hands.

By the time the figure in the sky had become familiar - seasonally present, geometrically reliable, visually striking - it would no longer have been neutral. Form invites function. What is seen as a figure soon becomes read as a force. And in this case, that force was the storm.

The association between Orion and the storm is not arbitrary. In the highlands around Ararat, Orion’s seasonal appearance correlates with the coldest, darkest months of the year. These are the months when snow closes mountain passes, when winds surge through stone valleys, and when lightning cracks against the black dome above. These are the months when survival is uncertain, when the memory of light and warmth seems distant. And in that season, Orion rises - a figure in the sky, bearing what appears to be a club or weapon, facing the bull, standing at the breach.

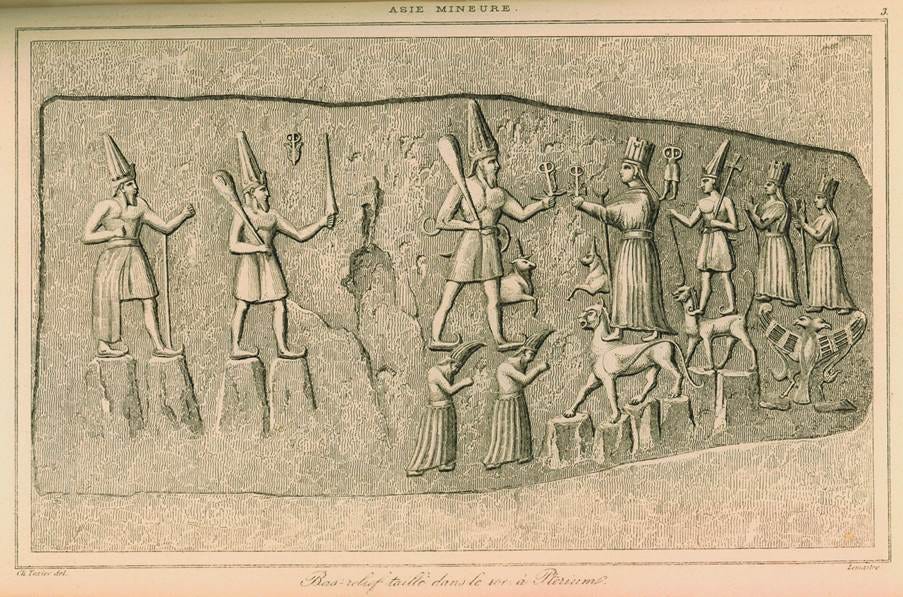

The earliest storm gods in the highland and northern Mesopotamian traditions share this posture and domain. The Hurrian Teshub, for example, is consistently depicted standing between twin mountains, holding a triple-pronged weapon in one hand and a circular symbol of rule in the other. He is not crouched, nor kneeling. He stands, wide-set, armed, facing forward. Likewise, the Hittite Tarhunt, and later the Urartian Haldi, all appear upright, dominant, often placed atop peaks or animals - visual echoes of Orion’s sky stance.

Image 7 - Teshub stands on two deified mountains (depicted as men) alongside his wife Hepatu, who is standing on the back of a panther. Behind her, their son, their daughter and grandchild are respectively carried by a smaller panther and a double-headed eagle. Engraving from a relief at Yazilikaya by French archaeologist Charles Texier (1882). – see https://www.worldhistory.org/image/10339/yazilikaya-engraving-with-hittite-gods/

These gods are not solar, nor lunar. They are not distant creators or grain-givers. They are cosmic enforcers - those who bring order in the season of threat. They are invoked not for fertility or harvest, but for protection, clarity, and the restoration of balance.

In this sense, Orion is not the storm. He is the one who stands in the storm unphased. His role is not to destroy but to face. Not to sow, but to judge. In times of disorientation - climatic, cosmic, existential - this figure in the sky becomes a mirror for endurance and re-alignment.

This is the root of the storm god archetype as it will unfold through later mythic systems. It is not simply that Orion was imagined to be Teshub. It is that Teshub was recognized in Orion. The sky provided the posture. The storms provided the context. The figure became god by appearing when he was most needed.

At Ararat, this recognition would have been reinforced by visibility: Orion appearing above the twin peaks during the winter sky, directly aligned with the region’s most prominent topographic feature. The mountain framed the god. The god faced the sky. And below, the people watched. And in the storm, the figure stood. And the archetype took form.

The Ark Within Orion

The ark, in its earliest conceptual form, is not a boat on water. It is a place of containment - a circle, a box, a mount, a sanctuary. And in the earliest sky-encoded traditions, this space of survival and orientation is not below the storm god, but in him.

If Orion is the figure who stands in the storm - the one who reappears after the flood of sky has drowned familiar markers - then it is only natural that he would also become associated with the structure of survival. His form not only endures the storm. It houses something. It preserves.

It preserves order. It preserves hope. And it preserves the people’s trust in the return of that king’s guidance - the good shepherd, crook in hand, who will always return and be reborn. Even when all is chaotic down here and resilience is the only way forward, there is always the promise: the king will return. And with him, order.

Within the pattern of Orion, this idea is visually reinforced. The three belt stars form a stable base. The stars above and below create a symmetrical enclosure. The “sword” or “hanging line” beneath the belt suggests both depth and entry. The whole figure, when traced, becomes a vessel - curved, bounded, oriented.

Across multiple early cultures, the ark is linked not only to a place, but to a group: the saved, the chosen, the wise. In Mesopotamian and later biblical traditions, this is the family or remnant preserved from flood. But in the oldest cosmological strata, the idea connects to the stars. These were the original forms: the ‘seven,’ the shining ones, the sages - the so-called Anunnaki (a term likely derived from Anu, the sky god, and possibly Ki, the earth goddess - meaning, symbolically, “those who bridge heaven and earth”). These early ‘gods’ would later become angels through Judeo-Christian iconography; and through the historicization and literalisation of symbolic figures, some would ultimately reappear as saints - no longer celestial patterns, but imagined as living people.

In the Egyptian cosmology, the original One - Atum - does not act alone. He creates through emanation: by spitting, sneezing, or splitting into the first pair (Shu and Tefnut), and then producing further divine aspects. These emanations were later conceptualised as assistants or aspects - the Ali or Ari - who carry out functions of measure, balance, and formation.

The Ari were known as the "doers," the divine limbs or agents through which Atum operates. Gerald Massey identifies these as the root of the Hebrew Elohim - not as “gods” in a separate sense, but as facets of the One functioning in plurality. In this way, Elohim becomes a reflex of Atum and the Ali: the One and the Seven, the Source and its Aspects.

In hydronym-related terms, AR, ALI, ARI survive as high, shining, or royal designations - but originally, they marked function, not bloodline. Just as rivers like the Araxes, Arno, or Arran carry the phoneme of height or origin, so too did the divine Ari/Ali denote agency from above. They were the river-currents of cosmic order - not elites, but emitters.

Thus, where Waddell saw ancestry, we restore function. Where religion imposed singularity, we reveal structured plurality. And in the Anunnaki, the Elohim, the Ali of Atum - we see the same pattern refracted through language and land.

Therefore, we see clearly why there exists an apparent paradox in the name for a singular god expressed through a plural word: Elohim. Its origin, as traced through rivers and streams of phonemic derivation, reveals not contradiction but structure - a unified concept formed by manifold expressions. It is seven rivers flowing into a single sea. And along the way, each river carved its own valley, grounded its own form, and nourished its own tributaries. Some flowed into new rivers, merging with other myths. Others dried up, leaving only stone impressions. But once the form was established - once it was ‘cast’ in stone - it became Law. Fixed. Singular in devotion, though plural in origin. From that fixed form came new flows: tributaries of doctrine, channels of meaning, each one a derivative of the original convergence.

Orion’s close proximity to the Pleiades - a tight, brilliant cluster of seven stars - is central here. He appears to face them. The beast (Taurus) stands between. In many sky myths, the Seven are pursued, protected, or carried. In some, they are hidden in the ark. In others, they are the ark itself - a bundle of wisdom preserved through chaos.

Furthermore, Orion’s own main form is also comprised of seven dominant stars. The god who emerges from this formation - upright, armed, seasonal - is not singular in spirit, but sevenfold in nature. These are the Seven-in-One: a figure of containment and composite force. This aspect will re-emerge later, profoundly, in the Egyptian sahu form of Osiris, and again in the Judaic concept of the “seven spirits before the throne.”

If we take this visually, then Orion is not only a figure of judgment or defiance. He is a carrier. His structure - fixed, geometric, central - becomes a pattern of retention. And this may be the original idea of the ark: not something that rides out a storm, but something that holds the pattern through disorder. A memory architecture. A cosmic vault.

Later traditions - from Egypt’s ship of the sahu to biblical arks to medieval vessels of grace - all echo this deeper structure. The ark is not technology. It is continuity. And Orion, seen rising each year after the disorientation of winter's darkness, is the visual frame through which early people located that continuity.

He stood in the storm. And within him, something was kept. Not just life - but order itself.

The ark was not beneath him. It was drawn in his shape.

Teshub, Tarhunt, Haldi: Sky Gods from Orion

As the visual presence of Orion became familiar in the winter sky above the Ararat region, it began to draw associations that would crystallize into the earliest storm god identities. This process did not begin with scripture, cult, or dogma. It began with recognition - a continuity of observation layered over generations, until the figure in the sky was seen not merely as a shape, but as a being.

The Hurrian storm god Teshub, one of the earliest sky deities clearly identifiable in the highland traditions north of Mesopotamia, is typically depicted standing between two mountains (Namni and Hazzi), armed with a thunderbolt and often facing a bull. He is not seated. He is not veiled. He stands, armed, confronting opposition - mirroring the stance and positioning of Orion.

In iconography, Teshub’s stance mirrors Orion’s upright posture. His arms hold weapons; his feet are planted wide as if atop peaks. He does not descend from heaven - he occupies it. He is present in the breach, just as Orion is when he rises above the broken horizon in winter.

The Hittite version of this figure is Tarhunt - also associated with thunder, rain, weapons, and kingship. He is invoked not merely as a weather deity but as one who brings justice and upholds the cosmic order, especially after disruption. His slaying of the serpent Illuyanka reinforces his role as a restorer of stability after primordial chaos. Again, the Orion template applies: the storm god as cosmic enforcer.

Teshub’s slaying of Illuyanka is not a quaint regional legend. It is a variant - barely disguised - of the storm god archetype defeating the chaos-serpent, a myth repeated endlessly because it encodes the same structure seen and felt across time. The image is always the same: the upright god or warrior, often star-borne or mountain-rooted, wielding a thunderbolt, a staff, a weapon of axis. And before him coils the dragon-serpent of chaos, of shadow, of obstruction. The deity rises-not from heaven, but from the horizon breach, from the earth-sky tension point. He stands, like Orion, against the great writhing disorder and forces it into form.

Illuyanka is Leviathan is Apap is Tiamat is Vritra is Jörmungandr is Python. To deny this is to deny the very basis of comparative mythology. Each of these dragons emerges from the deep-whether called the abyss, the Nun, the Tehom, or the primordial waters. And each is struck down by the arm of order. These are not borrowed tales. They are not parallel developments. They are the same structure speaking through different tongues.

And yet, academic consensus insists they are “unrelated.” Because the cultures were “different.” As if archetypes care about borders. As if stars change their shape depending on which kingdom draws the maps. The claim is not just absurd-it’s anti-historical. It ignores trade, transmission, conquest, intermarriage, linguistic shift, memory, and above all, the sky. The very claim that ancient peoples separated by geography could not share cosmological myths reveals a deeper blindness: a refusal to acknowledge that the same sky rose over them all. They were not copying each other - they were encoding the same pattern in the only language they had: serpent and staff, flood and fire, hero and beast.

This repeated denial-that Illuyanka and Leviathan have “no connection” - is not born from reason. It is born from an inherited need to shield biblical myth from its ancestry. Because if the storm god’s battle against the serpent is shared - if Yahweh, too, is also derived in part from the warrior in the same celestial script - then the entire edifice of uniqueness begins to crumble. The biblical editors tended to flatten Leviathan into a demonic cipher. But the skeleton remains. You cannot unsee the coil once you know where to look.

The consensus view collapses because it is not built on logic-it is built on compartmentalization, enforced silence, and reverence for a literary illusion. Once you reassemble the fragments-once you restore Illuyanka to his place in the cosmic cycle-you see the whole picture. And you understand why the upright god stands just so. Why he holds the staff. Why he waits at the edge. He is not just the storm-bringer. He is the axis - Orion risen - standing in defiance of the serpent that always comes. And always will.

In the later Urartian context, the sky warrior becomes Haldi, the chief deity of the Urartian pantheon. Haldi is often shown standing on a lion, holding weapons, his posture again matching that of Orion - forward-facing, wide-armed, in command. Haldi is invoked in war and kingship rituals, particularly in mountainous sanctuaries, reflecting the linkage between high places, divine alignment, and sky power.

These three storm gods - Teshub, Tarhunt, and Haldi - all share key traits:

· Standing posture, upright and armed

· Association with mountain peaks

· Confrontation with chaotic forces (beasts, serpents, storms)

· Seasonal timing aligned with winter dominance and astral visibility

None of these figures are solar. They are not fertility deities. They are sky enforcers - appearing in the dark season, wielding weapons, defending the axis, marking the return of recognizable form. Each of them embodies a specific reading of the Orion figure, shaped by local culture, language, and myth, but all rooted in the same seasonal appearance and sky-based pose.

What we see, then, is not a diffusion from a central cult, but parallel codification of an observed celestial pattern. The storm god did not descend from ideology - he rose from the horizon. Orion gave him shape. Winter gave him relevance. And the mountains gave him a throne.

The Bull as Beast of the Old World

The figure of Orion, weapon raised and gaze fixed, does not face an abstraction. Just ahead of his position in the winter sky stands the bright, unmistakable cluster of Taurus - the Bull. This stellar form, with its red eye (Aldebaran) and V-shaped horn pattern (the Hyades), becomes one of the earliest celestial adversaries.

In this arrangement - Orion facing Taurus - a visual narrative begins to suggest itself. One form is upright, armed, and symmetrical. The other is heavy, rooted, bestial. One advances. The other stands firm. It is not difficult to imagine early skywatchers projecting conflict into this scene. And in the presence of storms, darkness, and seasonal difficulty, the need for a cosmic struggle to explain the disorder would have been natural.

Across many Western traditions, this visual opposition is later encoded as myth. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the Bull of Heaven is sent to challenge the hero, only to be slain. In Hittite mythology, the bull is the mount or companion of the storm god - a beast tamed or mastered. In the iconography of Mithraism, the bull is pinned, held, and ritually slain - its blood or energy released as part of a regenerative act. In Egypt, at Saqqara, the Apis Bull becomes a mediator between gods and man - a living totem, ritually nourished and eventually sacrificed as an embodiment of divine presence.

The bull becomes a symbol of the prior world - a figure of unshaped power, instinct, and inertia. It represents both strength and resistance, but also a kind of blockage. In the sky, its placement between Orion and the Pleiades reinforces this reading: it is the barrier between the storm god and the cluster of “the seven” - the saved, the hidden, or the sacred. Those desired by Zeus, but never to be embraced.

Thus, the act of facing the bull - or striking it, slaying it, overcoming it - becomes a necessary act of world renewal. This is not about agricultural fertility in its earliest form, but about cosmic re-alignment. The bull must be displaced for the new order to advance. The storm god is not merely a destroyer - he is the breaker of the beast, the one who reopens the path to the light. He also represents the necessity of both the beast of burden and the necessary sacrifice for food for survival. All of these archetypal foundational concurrent themes ultimately must be rationalised by the intellect; and in doing so, over time, myth became multi-layered and complex.

And here, I would like to break from the narrative for one moment. This, I implore of you, dear reader: if there is but one message that you take home after reading this, is that it is folly to seek single meaning in symbols of mythic forms. Archetypes exist in purity, but become enmeshed in matrices of diversified symbols. To see only the sun in Horus, or Jesus, to see only the Devil in Set, purely as Satan, to see the Dragon only as an archetype of evil, or purely as the constellation of Draco, is to miss why Orion is also the ark as well as the Giant warrior or hunter, who also embodies the sun aspects of Osiris and Horus, and is also part of the matrix embodied in the myths of the planet Jupiter, is to miss the beauty of myth. Comparative mythology must be understood through this lens as a process of converging symbols and totems that emerge as stories, wherein Man has rationalised a set of concepts, and their totems or symbols, into a single codified narrative.

A 'thing' is never a 'thing' in isolation. It is both a consequence and a cause. This is what is clearly inherent in the earliest mythologies: that the force, the 'field' many call God - that omnipresent and omniscient energy - manifests in diversity, not singularity. It recurses, refashions and reforms in an eternal evolution. It is expressed both in Nature and the mind of Man. Whereas, Man's tendency is to need to understand through codification, linear meaning, logic etc. But logic that arbitrarily selects the database from which it derives biased conclusions is also folly.

And here is a perfect case in point:

Marduk, as Jupiter, embodies the function of returning time - the planet that slows, reverses, and resumes motion, visibly marking celestial periodicity. He observes, measures, mediates. He is not the god who stands in the breach - he is the one who sees that the breach returns.

This is a Chronian function - long before the Greeks personified Time as Cronus, and even longer before Cronus was conflated with Saturn.

To say Marduk, as symbolised by Jupiter, is "like Chronos" is not to confuse Jupiter with Saturn. It is to say that the archetypal function of Time - of celestial oversight and return - was embodied in Jupiter’s behaviour, long before Time was deified, named, or shackled to a planetary shell.

The problem with Man’s compulsion to codify into singular correspondences is best expressed symbolically as the concept that: God created everything, He created Man with free will, then Man used that freewill to reinvent God to suit his own purposes.

To continue with our story.

Seen from Ararat, this visual tension would be particularly pronounced in the winter sky. As Orion rises fully, Taurus stands ahead, blocking the way to the Pleiades. The bull is not metaphor. It is ever-present, bright, cantered.

The storm god’s weapons - whether club, sword, axe, or bow - are not chosen arbitrarily. They arise from the posture required to confront a charging form. And in the sky, that form is the bull. It defines the challenge, and thereby defines the god.

In later systems, this archetype will fragment: the bull becomes associated with earth, fertility, kingship, sacrifice. But at its origin, it is the obstacle to be faced - the beast at the gate. And Orion, as storm god, is the one who does not flinch.

He rises in the night, not to command the stars, but to oppose the beast that blocks the seven. The old world must be met before the new one can be restored.

The Cross, the Staff, and the Sword

In the figure of Orion, early observers saw not only a stance or a direction - they saw the implicit presence of tools. These were not drawn in art or carved in stone at first. They were simply read from the stars.

The stars of Orion are arranged in a way that naturally suggests weaponry and symbolic implements. The line of three stars that forms the belt - Alnitak, Alnilam, and Mintaka - sits horizontally across the middle of the figure. Above it, Betelgeuse and Bellatrix. Below, Saiph and Rigel. The sword or hanging object - often portrayed today as Orion’s scabbard or a nebular trail - descends vertically. These lines, when mentally connected, produce recognizable forms:

· A cross, symmetrical and upright, formed by the vertical and horizontal axes.

· A staff, extending down from the belt as a sceptre, suggesting guidance or authority. Or the one held as a shepherd’s crook in his right hand.

· A sword, pointed and descending - an object of division, judgment, or combat.

These forms do not require interpretation. They are visible. And in a culture accustomed to reading meaning from nature - where a tree, a horn, or a hoofprint might bear significance - the presence of these shapes in the sky would have been both compelling and persistent.

Each object associated with Orion carries a potential function in the emerging storm god archetype:

· The cross becomes a symbol of axis - where heaven and earth intersect, or where the four directions are held in balance. It is not originally a sign of suffering, but of orientation and poise.

· The staff is the emblem of shepherds, kings, and guides. It evokes stability, support, and the right to lead. It is the inverse of the club: a tool that governs, not strikes.

· The sword is the most unmistakable of all. It is the breaker, the divider, the instrument of decisive action. It hangs not at the hip, but beneath the belt - suspended, visible, imminent.

· The belt would later come to define a central axis also as the 3. 3 ‘wise men’ or minor ‘kings’ that traverse to find the One true meaningful coming saviour. The sun god incarnate that brings the life through the light. The 3 that seek the 2 that created the One. And the direction is already encoded in the form of the 3 stars that point directly to where the Mother abides, as Sirius or Sothis, Isis, the Meru mother herself.

These shapes are not later inventions projected back onto the stars. They are sky-given patterns, available to anyone who watched. And over time, as the storm god took on more defined cultural roles - judge, warrior, guardian - these instruments were ritualized into myth and theology.

In later iconographies, we see these tools recur with striking consistency. The storm god wields a rod or sceptre. He carries an axe or sword. He stands upright with arms flared - often within or above a cross-like framework. In Christian iconography, the same pose appears in the crucified figure, the risen king, the enthroned judge. In Norse myth, it is Thor with Mjölnir. In the Arthurian cycle, the sword in the stone, the lance, the staff of the wounded king.

But all of these echo a prior visual logic. One directly observed for millennia, before any myth was ever written or drawn into hieroglyph, or carved into rock.

At Ararat, Orion rises each winter with the same orientation: cross-formed, staff-stabilized, sword-suspended. He is clearly masculine in form, with that sword primarily as phallus. He is not imagined with these items - he is seen with them. In this way, the implements of judgment, order, and force become encoded not by cultural decree, but by astral geometry. The storm god does not pick up the sword. He contains it.

And in times of upheaval, it is this silent promise - that something still holds the axis, still wields the staff, still carries the blade - that made Orion more than a shape.

He became a symbol of power not by myth, but by form.

The Seven Beyond

Beyond the bull, just past the confrontation point in the winter sky, lies a tight, luminous cluster of stars - the Pleiades. Known since antiquity as the Seven Sisters, they have been mythologized in virtually every culture across the Western world and beyond. But long before they were called by any name, they would have been simply seen - compact, glinting, distinct from the surrounding stars, and unmissable from the clear night sky over Ararat.

If Orion is the storm god, the figure who stands armed in the face of chaos, and Taurus is the beast of the old world, then the Pleiades represent something else entirely: the prize beyond.

This cluster, small yet brilliant, appears tucked behind the shoulder of the bull. It seems just out of reach from Orion’s stance, as if guarded by the intervening beast. To early skywatchers, this spatial relationship would have suggested movement, intent, and pursuit. The storm god confronts the bull - not only to break it, but to reach what lies beyond it.

Across many traditions, the Pleiades are associated with sacred sevens: seven spirits, seven sages, seven flames, seven daughters. They are called the lost, the hidden, the mourned, the saved. Their smallness is deceptive - they are symbols of wisdom, preservation, and cosmic inheritance.

The positioning of the Seven beyond the bull gives rise to a core narrative structure: the hero must confront a challenge to reclaim or release the sacred. The beast is not the goal. It is the gatekeeper. The Pleiades are what endure. They are what must be retrieved.

In this way, the storm god’s role is not only martial or defensive - it is restorative. He clears the path. He reopens access. He returns the pattern. And in the sky, this story is laid out in spatial sequence: Orion (the figure) → Taurus (the obstacle) → Pleiades (the preserved).

Even the storm god’s weapons echo this trajectory. The thrown hammer, the hunter’s throw stick, the shot from the sling, the flying arrow, the reaching staff - all imply a motion beyond the bull, as if the true act is not striking the beast, but passing through it to touch what is hidden.

From the highlands around Ararat, this sequence is stark and recurrent. In the dark of winter, Orion rises in his full form. Taurus blocks the way. And the Pleiades shimmer just behind, as if waiting. In the mythology that follows, this configuration will give birth to thousands of variants - the slayer, the gate, the maiden, the lost ones. But their root remains observational. It is a story written in stars.

The Seven are not always reached. Sometimes they remain beyond. But their place in the sky gives the storm god’s confrontation its purpose. Without them, the beast is just violence. With them, it becomes the path back to the sacred.

The Seven lie beyond. And the god - in his own sevenfold form - who rises, must face the bull to find them.

The Birds and the Return

If the bull marks the confrontation and the Seven represent the preserved pattern beyond it, then the next step in the sequence is return - not in the linear sense, but in the cyclical rhythm that underpins the entire sky-based tradition. In this turning, a new figure enters the story: the bird.

Across ancient Near Eastern and highland traditions, birds are the first messengers of return. In the biblical flood story, a dove is released from the ark to search for land. In Sumerian and Akkadian accounts, multiple birds - including ravens and doves - are sent in search of solid ground. In Anatolian burial iconography, vultures are depicted carrying the dead toward the sky. In Egyptian cosmology, birds hover at the threshold of rebirth.

Why birds?

From a skywatcher’s perspective, birds are the only terrestrial creatures that rise toward the stars. They traverse the boundary between ground and sky. They disappear and return. And in seasonal migration, they mark time with a precision that rivals the heavens.

In the Orion-based sky pattern over Ararat, birds are not explicitly depicted - but they are implied. The entire form of the seven stars can be seen as wings pivoting from the central 3 stars. Orion, thus, is an early icon of the bird or the angel.

The bright star Sirius, rising below, was associated in multiple cultures with soul-journey and divine messengers. The entire vertical path from Orion down to Canis Major becomes a corridor - a flight path.

The return of the bird signifies that the cycle has turned. The waters are receding. The flood has ended. The axis is restored. But this return is not just about safety - it is about re-approach to the sacred. The bird returns with a sign (a branch, a direction, a landing). The observer watches the sky for this signal. It is not only salvation - it is alignment.

In early cult and myth, this returns in countless forms: the soul-bird, the phoenix, the eagle of the storm god, the dove of the spirit. In each case, the bird is both a guide and a proof - something that emerges from the unknown with evidence that re-integration is possible.

From Ararat, this pattern would have been naturally recognized. As Orion descended in spring and the bull waned, birds returned physically to the valleys - and were mirrored above in the same regions of sky. Their call became a cue: the wheel is turning. The god who stood in the storm has passed, the beast has receded, and the Seven remain in place.

The return of the bird is the final reassurance. It bridges the sky and earth. It completes the arc of disorientation, confrontation, and survival. And it sets the stage for memory: the next time the sky begins to break, the observer remembers - the bird will return. The pattern holds.

In the oldest sky stories, there is no end. There is return. And it is the bird that tells you when to begin again. Moreover, the bird may also appear as eagle, falcon, or hawk - the high-flying form of the ultimate Saviour figure - who is, eternally, the Sun itself.

The Fragmentation of the Pattern

By the time Mesopotamian cities had risen, scribes had etched cuneiform, and organized religion had begun to codify the sky, the original storm god pattern had already begun to fragment. What had once been a seamless sequence of sky-encoded figures - Orion rising, confronting the bull, reaching the Seven, marked by bird-return and cosmic renewal - was gradually restructured, moralized, and localized.

In Akkadian texts, the storm god becomes Adad, wielding lightning, sending rain, and thundering from above. In the Babylonian Enuma Elish, Marduk rises not from observation, but from a political theology. He slays the chaos-serpent – the embodiment of the heavens in its primal form as endless sea – Tiamat - creates the world from her body, and becomes king of the gods. The visual sky structure is retained in parts - the dragon, the weapon, the heavens above - but the clean orientation of the Orion–Taurus–Pleiades pattern is overwritten.

Part of the reason is that Marduk is also Jupiter - the crossing planet of return - the watcher, the timekeeper. He sees all, mediates change, and accounts for the unfolding of worldly states. He is aloof, distant, not the god who stands, but the one who tracks. A kind of cosmic Chronos (long before Chronos became associated with Saturn).

By the time of the Hebrew redactions, the storm god has become Yahweh - a divine warrior, a judge, a bringer of the flood, and vengeful. Yet his cosmic role is reframed through a moral and covenantal lens. The ark becomes a vessel of obedience. The flood becomes a punishment. And the figure in the sky is no longer described. The orientation is now ethical, not astronomical.

He retains form as the god of the mountain - pronouncing the Law written in stone - but his fullness as Orion is not expressed in that episode on Sinai. The archetype of the mountain god is preserved, yet the skyfield or skysea that once gave him shape has been veiled.

In Egypt, echoes of Orion survive more cleanly. Sah, the stellar form of Osiris, is linked directly to Orion’s stars. He is the risen one, the judge, the soul-ferrier. But even here, the older logic of seasonal re-emergence and confrontation with chaos is woven into complex theologies of kingship, afterlife, and solar union.

In Greece and Rome, the storm god appears as Zeus, Jupiter, Ares, Apollo, fragmented across functions - sky-ruler, storm-bringer, light-giver, archer. The original form is no longer single. The weapon and the beast, the Seven and the return, are distributed into myths and mysteries.

By the time the Christian figure of Jesus emerges, Orion’s sky-form has been broken into symbols. The cross, the sword, the staff, the lamb, the fish, the king, the judge - all can be traced to segments of the older figure, but they are now encoded through doctrine and allegory. The flood is moral. The ark is salvific. The bird is the Holy Spirit. The Seven become churches, spirits, lampstands.

The visual grammar is retained. But the unified field is gone.

And yet - the sky remains. Orion still rises. The bull still stands ahead. The Seven still shimmer just beyond. Each winter, the sequence plays out exactly as it always did.

The fragmentation of the myth did not erase the pattern. It only shifted it into language. For those who know where to look – who remember the order, not the stories – the original form is still visible.

Just look up.

As is often said, the Mysteries are revealed to those “with eyes to see and ears to hear.” And now we see the Storm God – and hear his thunder – in all his fullness.

From Ararat, beneath the winter sky, the storm god still stands. He still faces the beast. The Seven still lie beyond. And the bird will return.

EPILOGUE: The Sky Did Not Lie

The oldest truths were not written - they were watched.

From the highlands of Ararat, in winters long before history, the sky presented a sequence. No doctrine explained it. No prophet foretold it. But it was there: a figure rose. A beast stood before him. Beyond the beast, a cluster of lights. And each year, in the same season, the pattern returned.

Orion. Taurus. The Pleiades. Jupiter. In this Primary Nexus - together with the sun and moon - they formed the first mythic structure, not as a story told, but as a shape seen. The storm god did not descend from belief. He emerged from observation. The figure who stood in the dark, weapon raised, at the time of year when cold and silence ruled, became the first articulation of endurance. And that endurance became divinity. But first - and first to impress the eye and the mind - was Orion. All else follows from that. Whatever surrounds Orion becomes part of the myth’s structure - not by chance, but by necessity. And through necessity: inevitability.

The early skywatchers did not require theology to build coherence. They required only continuity. And Orion gave them that. So too did the bull, as obstruction; the Seven, as recovery; the bird, as return.

Later systems would overlay this with names, creeds, and covenants. But the foundation was never erased. Even now, under open sky, the sequence plays on. This is the story that began in Ararat, where the mountain framed the god, the god faced the stars, and the people remembered.

And though the myth would be broken, revised, reissued - the sky did not lie.

It still doesn’t.

Each winter, the Storm God rises again.

APPENDIX - The Name Survives: ISH–KUR as Proto-Typology

The storm god Ishkur is not simply a Mesopotamian deity with a localized cult. His name, when broken down, encodes a phonemic structure with deep resonance across Western Eurasia. The name ISH–KUR consists of two elements, both of which have independent semantic histories that persist across time, languages, and geography.

ISH denotes agency, masculinity, and often fire or force. In Sumerian contexts, ISH carries active connotations - one who acts, speaks, or strikes. In later Semitic usage, such as Hebrew (ish, אִישׁ), it explicitly means "man." In Indo-European branches, the same phoneme survives as ash, asir, sir, and sar, found in honorifics ("sir," "sire"), in mythic collectives (Norse Aesir), and in sovereign designations (kaisar, Caesar). Waddell links Ash directly to royal and divine titles in early Sumer and the Indus Valley, treating it as a governing root for high kings and deities alike.

KUR, in Sumerian, is the land of opposition - the mountain, the foreign land, the place of darkness or descent. It means mountain, land, or even the underworld, depending on context. It also appears in compound names for kings and gods who straddle thresholds: rulers of mountain regions, agents of flood, or underworld intermediaries. Phonetically, kur survives in hydronyms across the ancient Near East and Europe as kar, gar, gur, ker, and kor. These are often found in mountainous river basins or along rugged boundaries, places long associated with divine activity.

Taken together, ISH–KUR communicates a very specific cosmic function: the masculine enforcer who emerges at the boundary – between storm and land, between heaven and mountain, between order and flood.

This is not etymological coincidence. It is linguistic memory. The storm god’s name was not invented to explain a myth. It was the natural encoding of an observable pattern: the upright figure (Orion), rising in the winter sky, standing at the breach – the mountain where land meets sky, where land meets the sea of space, or in the case of Teshub at Ararat, the space between twin peaks – facing the beast (Taurus), framed above rivers that roared with flood.

Ishkur is a title that names the function already read from the Primary Nexus. It is through him that the phoneme ISH–KUR entered the mythic, linguistic, and topographic consciousness of the early world - and from there, survived.

Waddell’s Vision: The Suppressed Origin of Kingship and Language

The work of L. Austine Waddell, once dismissed by mainstream academia, now proves essential for reconstructing the buried lineage of kingship, language, and symbolic structure across Eurasia. His bold claim that Sumerian was not a linguistic isolate but the proto-source of Indo-European phonology aligns with what we now recognise in phonemic continuity across hydronyms, sovereign titles, and mythic names.

Waddell identified a recurring set of root phonemes that appear in the names of early gods, rulers, rivers, and mountains: ASH, AR, SIR, KUR, GAL, and UR. These were not arbitrary syllables. They carried meaning and function. Ash or Ish marked agency and divinity. Kur indicated mountain, boundary, or hardness. Sir and Sar signified rulership and high status. Gal meant great or exalted. Ur denoted primacy or origin.

When combined, these elements formed the scaffold of Sumerian royal nomenclature - and, Waddell argued, later reappeared in Aryan, Phoenician, Gothic, and early British titles. The figure of Ishkur fits this matrix precisely. His name includes both the storm-agent (Ish) and the threshold or opponent (Kur). This positions him not just as a weather god, but as the archetype of the one who stands at the cosmic gate - the enforcer at the mountain.

Waddell showed that the title Ashur, long considered an Assyrian tribal god-name, was actually a compound of Ash (agent) + Ur (origin). Likewise, the names Ashkan, Ashir, and Asar (Osiris) preserve this root, as does the collective term Aesir for the Norse gods. These were memory fragments - echoes of Ishkur’s storm-title surviving under regional variations.

By restoring Waddell's system, we do not claim that every name with ash or kur must refer to Ishkur. But we do claim that the survival of these phonemes across time and geography is not random. It reflects a continuous memory - a suppressed grammar of power, embedded in both speech and structure.

Waddell’s vision, long neglected, becomes indispensable when viewed through the lens of phonemic persistence and skyfield orientation. The name Ishkur was never isolated. It was part of a living code.

Hydronymic Memory: Rivers as the Hidden Record

Rivers preserve memory. Where temples crumble and dynasties vanish, the names of rivers endure. In them, we often find the last surviving traces of mythic systems, preserved not in writing, but in sound.

The phonemes associated with Ishkur – ISH, KUR, GAR, GUR, KAR, KER, UR, GAL – appear widely across the hydrological landscape of Western Eurasia. From the highland arc around Ararat to the river systems of the Balkans and Central Europe, these root sounds surface repeatedly in rivers that flow from mountainous terrain or through culturally significant thresholds. They also survive in later water-linked place names such as Galway in Ireland and Galashiels in Scotland. Galway is defined by its bay, whose rocks have been worn down by the sea. Galashiels, similarly, lies at a river bed scoured and shaped by flowing water into a shiel – a shell, a cradle of structure. This is the action of a chreode: the solid worn by water to become solute, and the groove or channel into which the solute flows.

Consider also:

· The Kura River (Caucasus)

· The Karun (Iran)

· The Korana (Croatia)

· The Garavica (Bosnia)

· The Ishim (Kazakhstan/Russia)

· The Asker (Norway)

· The Gur River (Iran)

· The Kars region and river tributaries near Ararat

These names are not uniform in language, yet the phonetic pattern is persistent. They appear disproportionately in storm-prone, flood-bearing, or mountain-fed river systems - precisely the sort of environments associated with divine or mythic activity.

In the hydronymic framework, these phonemes represent more than etymological residue. They encode a geographic memory of the storm god’s domain: the place where water meets rock, where flow breaks against resistance, where the heavens open. This aligns precisely with the storm axis of the Primary Nexus.

Rivers, lakes, and springs were not just natural features. In the early mind, they were thresholds – entrances to the underworld, barriers between domains, sources of life, and channels of death. That the storm god’s name survives in them is not incidental. It suggests a cosmology in which divine agency was located not only in the sky, but in the course of water cutting through the land.

Thus, the ISH–KUR phonemes embedded in river names become an unbroken record. They are the forgotten script of the god who stood above the peaks, whose voice was thunder, and whose passage was flood. They flowed even when the myths were lost.

The rivers remember what the scribes tried to silence.

As cultures consolidated and religious systems formalised, the early storm god figure embodied by Ishkur was not merely forgotten. He was overwritten.

In the Mesopotamian scribal tradition, the name Ishkur was gradually absorbed into the Akkadian Adad, and later conflated with Semitic deities such as Baal and Hadad. While these later gods retained aspects of storm-force, the linguistic encoding of ISH–KUR was progressively obscured.

Waddell was among the first to note that modern Sumerology, shaped largely through post-biblical and Assyriological filters, reversed the direction of influence. Sumerian was made to appear as a derivation or isolate, rather than the origin. Lexical lists were often reconstructed using the Hebrew alphabet or through lenses shaped by rabbinical tradition. This skewed the record and disrupted the recognition of phonemic continuity.

As a result, the phonemes ISH, KUR, AR, ASH, and SIR, foundational to early divine and royal names, were fragmented across traditions. Ishkur became Adad. Ashur became tribalized. Asar (Osiris) became severed from his Sumerian precursors. The same pattern holds in the Greek and Roman worlds, where the storm axis is divided among Zeus, Ares, and Jupiter, each carrying only a part of the original function.

The process was not random. It reflected a shift in theological control. Where early storm gods represented raw elemental force and direct cosmic engagement, later deities were tied to moral law, covenant, and institutional authority. The storm became a narrative of punishment, not balance. The names changed accordingly.

Even within the Hebrew tradition, echoes survive. The god who sends the flood. The voice in the storm. The one who appears on the mountain. These are the residual functions of Ishkur, relabelled to fit a monotheistic framework. But the name is gone. The posture remains.

This erasure was not complete. In river names, in mountain terms, in honorifics and tribal memory, the phonemes persisted. But the god was no longer recognised. The scribes broke the name into parts, spread it across pantheons, and left only the fragments.

Reconstructing Ishkur, then, is not simply an exercise in etymology. It is a restoration of what was systematically dismembered - a reassembly of the storm axis from the scattered syllables of ancient control.

But what of Ishkur’s Consort: The Feminine Forms of the Waters?

While Sumerian texts do not pair Ishkur with a single, fixed consort the way later pantheons do, the archetypal pairing is unmistakable – and her forms are legion. She is not always named beside him, but she is always present in function. Across cultures, she emerges in water, earth, and star-aligned forms:

· Inanna / Ishtar – Often paired with Dumuzi or symbolically aligned with Tammuz, but functionally mirrored to Ishkur as the one who descends and returns. She governs waters, love, battle, and fertility – she is the field through which storms pass and renew. The storm god's masculine thunder finds release in her domain of blood, birth, and seasonal resurgence.

· Anu / Ana / Dana – The mother goddess as sky, as well as the deep. In Celtic forms like Danu or Donu, she becomes the very source of rivers (the Danube = Danuvius), feeding the landscape that the storm god reshapes. She is also Anunitu in Akkadian – sometimes a title for Ishtar, other times a distinct water goddess.

· Tiamat – In the Babylonian inversion, she is cast as the chaotic sea – the very field Ishkur's later proxy, Marduk, slays. But originally, she is the origin – the divine waters out of which form emerges. She is not chaos – she is the matrix.

· Ereshkigal – In the underworld sense, she is the deep well, the silent counterbalance to Inanna’s visible passage. She receives all things, including the dead. Her domain, too, is shaped by the descending force of the storm.

· Nammu – One of the earliest Sumerian goddesses, the primordial sea. She gives birth to heaven and earth – the original field before the storm.

· Apsu / Abzu – Though often gendered male in later texts, the abzu was originally a feminine-coded depth – the underground sweetwater sea, sacred to Enki/Ea but receptive to the storm’s descent and lightning strike.

· Ninhursag – A mountain and fertility goddess whose name means "Lady of the Sacred Mountain." She represents the union of high place and generative power. In Sumerian mythology, she is the nurturer, the womb of life, the one who shapes kings and grants the right to rule. In this role, she is not simply a consort, but a cosmic architect. She balances the storm with renewal, the strike with the seed. Her mythic terrain mirrors Ishkur’s: from highland thresholds and river origins to fertile fields sustained by her enduring presence.

It is from such hydronymic phonemes that the word mother brings the completion to the natural form as:

· Mater (Latin: mother)

· Matter (the substance of form)

· Matrix (the womb, the origin, the pattern)

· Meter (the measure, the rhythm)

· Maat (Egyptian: truth, balance, cosmic law)

· Mut (Egyptian: mother goddess)

· Mutter (Germanic root for mother)

· Ma (universal feminine root, Sumerian, Dravidian, Indo-European)

· Meru/Mary (Egyptian goddess form to feminine name)

· Mer, marsh, maritime, merchant, marriage, marry, and more modern words, all derived from the same ancient roots.

The word “matter” is not inert. It is the field. It is the womb. It is not what form stands upon – it is what form arises from.

When the Grail contains wine, it is mater/mother inside form. When Osiris is wrapped in Aset’s linen, it is matter containing the body of the law. When the IO axis forms through chreode erosion, it is matter shaping memory – the riverbed cut by return.

When the mummy, wrapped in swaddling bands, is made karst by organ removal and drying, it is then anointed by the feminine oil or resin - the moisture that returns to the petrified - as life to the dead. And in Egyptian, this is the addition to the hydronym krs of the feminine determinant t - forming krst, a word that eventually comes to signify the rebirth of the man as god, journeying back to the origin, to the sacred mountain in the afterlife, to become one with the Father.

Once again, it is the waters and the stone - the soft and the hard - reunited as harmony and balance, rather than friction and separation. The gar and the kar hydronyms reunite in krst. And this would come to form the root of that word so familiar: Christ.

He is anointed - the anointed one - whose clear, watery resin is a close analogue to the soul through spirit, or the breath of Atum: the Hu of IHUH (later YHWH), and the root of the name of Jesus as Yehoshua, derived from the older Egyptian Iusa, meaning “the eternally coming son.” The one who comes in peace: iu-em-hept, later known as Imhotep.

The one born in swaddling clothes becomes, in essence, the Egyptian initiate - the soul beginning the journey through the Duat, toward the mount, to be judged upon the axis of Maat.

There, he completes the arc - and spirals into natural form.

The eternal story of the hero - from innocence, through ordeal, to experience.

And in the modern Indo-European word “mother,” we preserve it all – not just biologically, but cosmologically. She is the very embodiment of the archetype that is 'the waters'.

· She is the solubility.

· He is the once-hard, now-contained.

· Together, they are the cycle of eternal becoming.

At the heart of the oldest linguistic strata lies a structural polarity: hard and soft, carved and flowing, masculine and feminine. This is not myth imposed on language – it is memory embedded in the phonemes themselves.

The hydronyms KAR, GAR, KUR, and KAL encode the hard, elevated, or cleft terrain – the masculine ridge, the threshold, the god-form that stands. These names mark rivers that cut through rock, or places where mountains breach the sky. They are the domain of the storm god – the figure who emerges at the break, who brings order through pressure and division.

The feminine counterpart is preserved in GAL, GUR, GALA, and related phonemes – the flowing, the deep, the fertile basin. These are not passive markers, but active forces – the river itself, the mouth of the spring, the valley that receives. In myth, she is the goddess – but in function, she is the formative field: the one who wears down, who softens, who holds.

The pattern recurs across geographies:

The karst terrain names both the rock and the erosion it suffers.

The gal and gala rivers bear names that speak of what they carry. In the Indian context, gala is also milk - the gal water (soft) containing the cal calcium (hard) solute: that which was once the form of rock, now internalised into the life-sustaining whole.

The kal is the ridge. The gal is the song of what flows around it.

And so the god emerges not in isolation, but in relation. He is carved by her. She carries him within.

The Grail is shaped by the water that once wore it smooth - its form once glinting in the sacred body of the mother’s riverbed.