Return of the Storm God (revised 5-11-25)

Chapter 1 - The Birthplace of Writing? The Bedrock of Myth?

Note - this is an idea for a cover only.

Contents

(for the full book - which is slightly different to the substack series, that links extra-Storm God articles from within - see note in the Preface)

Preface

Explaining the purpose of the book to restore the truths that religion has distorted.

Introduction – Orion and the Lost Structure of Truth

Orion is presented as the celestial axis behind all early myth, measure, and kingship, predating and uniting separate civilizations. Ancient cultures encoded proportion, geometry, and spiritual order into symbols derived from the stars and natural cycles. These truths were overwritten through theology, patriarchy, and centralized religion, obscuring their original scientific and symbolic functions.

CHAPTERS

Chapter 1 – The Birthplace of Writing? The Bedrock of Myth?

The Vinča script, discovered in the Danube basin, predates Sumerian writing by over a thousand years and reveals consistent symbolic sequencing. Carved into pottery and ritual objects, these signs suggest a sophisticated system of proto-writing linked to water, metalwork, and seasonal rites. The symbols were likely used to encode natural cycles, spatial orientation, and ritual authority in ways later inherited by Mediterranean and Mesopotamian cultures. This challenges the long-standing assumption that writing emerged first in Sumer. The chapter positions south-eastern Europe as a cradle of mythic language and sacred structure. It also suggests that many myths associated with later civilizations may have originated here in symbolic form.

Chapter 2 – The Danube-to-Sumer Drift: Reversing the Flow

This chapter reverses the conventional historical flow by showing that cultural, linguistic, and symbolic structures may have moved from the Danube into Mesopotamia. The author revisits and re-contextualizes Waddell’s theory, suggesting that sacred geometry, hydronymic naming systems, and metallurgy drifted eastward. Shared motifs between Balkan artefacts and early Sumerian structures reinforce this idea. The Drift described here is both physical and symbolic - it moves language, ritual, and cosmic models across land and time. The evidence includes phonetic parallels, trade routes, and symbolic diagrams. The chapter presents the idea that the origin of writing and kingship may lie not in a single place, but in a migratory current of shared symbolic logic.

Chapter 3 – The Rise of the Storm God

The archetype of the Storm God is derived from Orion’s pose and seasonal dominance in the winter sky, standing in opposition to the Bull (Taurus). This celestial event inspired figures like Ishkur, Teshub, and Baal, who act not as destroyers but as cosmic enforcers restoring harmony through thunder, rain, and light. The visual motif of the warrior between two peaks became a symbol of alignment and renewal. These gods emerged across regions yet shared common traits, suggesting a single astronomical archetype with regional variations. The Storm God’s purpose is to stabilize reality and reassert cosmic law. His rise marks the masculinization of myth while still preserving memory of the original celestial order.

Chapter 4 – The Rise of the Master Mythicist

Gerald Massey is reclaimed as the primary decoder of ancient mythology as scientific and symbolic language. His research showed that Osiris, Horus, and Jesus all represent mythic cycles tied to agriculture, solar movement, and human consciousness. Massey demonstrated that key elements of the Gospel story - virgin birth, twelve disciples, crucifixion, resurrection - were all present in Egyptian mystery drama long before Christianity. He argued that these stories were ritual patterns rebranded as history by later priesthoods. Massey’s work was largely ignored due to institutional hostility, not scholarly weakness on his part. The chapter places him at the heart of a symbolic restoration of ancient wisdom.

Chapter 5 – How the Hand of the Storm God Rocked the Cradle of Civilization

Sumer’s rise is presented as the result of a symbolic and technological infusion from the Danube-based Drift Culture. Figures like Enlil and Ninurta absorb the Storm God motif, bringing kingship, law, and temple construction as tools of cosmic alignment. However, these symbols begin to harden into hierarchical theologies and priestly control. The flood myth is used as a cosmic reset - a narrative tool to justify new orders and suppress older knowledge. Through mythic inversion, matriarchal and natural systems are overwritten by solar and masculine authority. This shift marks the beginning of sacred science becoming elite-controlled theology.

Chapter 6 – From Nature to Word, from Truth to Error

Language originally arose from living interaction with natural forces such as water, light, and wind - not abstract naming. Words like lugal (king) and shem (light-path or name) once reflected energetic conditions and cosmological functions. As political systems centralized, these terms were severed from their origins and repurposed for domination. The chapter explores how sacred words became fossilized, disconnected from experience. Many modern words still carry fragments of this lost structure. The author argues for linguistic archaeology as a tool to reassemble broken knowledge. The evidence exists that we still speak variations on these ancient languages and that Egyptian and Sumerian should be included in Indo-European etymological study.

Chapter 7 – The Story of Egypt

Egyptian myth encoded a balanced cosmology where Osiris, Isis, and Horus symbolized natural cycles, seasonal renewal, and sacred kingship. Osiris is not a historical king but a personification of the Nile’s death and rebirth, while Isis represents the generative matrix of fertility and cosmic balance. Horus, born of a virgin mother and destined to reclaim divine rule, completes the cycle. The chapter asserts that the entire Gospel story of Jesus is a deliberate retelling of this older Osiris-Horus myth, adapted under Roman imperial theology and rewritten as historical narrative. The virgin birth, temptation, crucifixion, and resurrection all originated in the Egyptian sacred drama. Christianity, in this light, becomes a symbolic echo of Egyptian cosmology, stripped of context and literalized into dogma.

Chapter 8 – The Realisation of the Axis: From Form to Stone

Before they were monuments, the axis structures were lived through seasonal rituals and field-based alignments. Later, ziggurats, pyramids, and standing stones materialized this sacred order into durable stone forms. These structures aligned with Orion and celestial cycles, acting as instruments of resonance between heaven and earth. Over time, their function was misunderstood, and their form fetishized as mystery rather than orientation. The twin-peaked symbolism of balance was suppressed in favour of masculine monotheism. The removal of feminine polarity distorted the original Egyptian model into the patriarchal cosmology of the Bible. Includes a major restoration of a lesser-known, but hugely significant axis archetype called Medjed.

Chapter 9 – The Drift into China

The Drift extended eastward, embedding itself in early Chinese cosmology through twin mountain symbolism, dragon myths, and sacred alignment. Language roots related to water and kingship suggest a shared Eurasian symbolic substrate. The text maps these transmissions before the Silk Road, identifying China as both recipient and preserver of westward cosmological knowledge. Shared rituals, astronomical models, and phonemes support this continuity. Chinese legends and myths mirror much of what was encoded in Sumerian and Egyptian frameworks. This chapter asserts a forgotten unity across continents, fractured only by time and conquest.

Chapter 10 – From Pyramids to Ptolemies: How Natural Science Encoded in Myth Evolved into Proto-Religion in Egypt

Egyptian myth functioned as a scientific system that preserved measurements of time, light, growth, and alignment. Its temple design, priestly calendars, and ritual cycles reflected precise astronomical and agricultural knowledge. Later priesthoods concealed this wisdom, transforming myth into theology and science into doctrine. With the arrival of Greek rulers and the Ptolemies, Egyptian knowledge was repackaged as esoteric religion. The shift from open measure to guarded belief systems marked a key transition in myth’s role. The original science survived only in fragments, hidden beneath liturgy and secrecy.

APPENDICES

Appendix I - Hydronyms

This appendix examines how ancient hydronyms, or river names, preserve some of the oldest linguistic and symbolic traces of sacred knowledge. Roots such as gar, kar, and val appear across Europe, the Near East, and Asia, consistently associated with rivers, valleys, and sacred places. These naming systems reflect a worldview that linked water, fertility, and feminine polarity with geography. Hydronyms functioned as living mythic signposts in the land, expressing an oral and spatial grammar. Patriarchal theology later overlaid these meanings with imperial naming systems, severing the symbolic connection. However, many of these names persist today, silently retaining the memory of the Drift Culture.

Appendix II - The Great Reset

Ancient flood myths and apocalyptic cycles were symbolic mechanisms for erasing old orders and installing new cosmologies. Stories like the flood of Noah served to destroy prior knowledge structures and justify new moral hierarchies. In modern times, institutions and media have used the same symbolic scripts to guide belief and behavior. The author warns that new ideologies, such as transhumanism or environmental catastrophe narratives, may function as reset myths for a technocratic age. These belief systems replace ancestral wisdom with centralized, institutional models of reality. The reset is not always sudden but can be introduced gradually through rebranded myths and cultural engineering.

Appendix III - Fringe Catastrophist Theories

This appendix critiques both academic orthodoxy and fringe theories that propose sudden global catastrophes or lost high-tech civilizations. The work of Graham Hancock is examined and challenged as overly speculative and reliant on literalist interpretations of myth. Sites like Göbekli Tepe are not evidence of Atlantis, but rather of ritual centers designed to preserve symbolic knowledge during environmental changes. Drift Culture is presented as a model of slow continuity rather than sudden collapse. The symbols found at ancient sites are treated as mnemonic tools, not lost technologies. The appendix encourages symbolic literacy over catastrophist imagination.

Appendix IV - Numerology and the Bible

Sacred numbers in the Bible, including 7, 12, 40, and 144,000, are traced to much older systems of natural measurement and celestial geometry. These numbers reflect the harmonic structures of nature rather than proof of divine authorship. Greek isopsephy and Hebrew gematria were techniques used by scribes to make words and texts conform to symbolic mathematics. What appears to be divine encoding is actually the human crafting of language using known principles of number, pattern, and proportion. The myths and texts were constructed around existing ratios such as phi and pi, not revealed by a deity. Sacred numerology in scripture is a continuation of Drift Culture’s mathematical storytelling.

Appendix V - Rome as the Greatest Liar in History?

Rome did not simply conquer land and people but also conquered narrative and symbolism by rewriting earlier cultural systems. Egyptian, Greek, and Mesopotamian myths were absorbed and altered to serve imperial theology. The Roman Church centralized doctrine and weaponized belief to erase indigenous symbolic knowledge. Myth was turned into literal history, and natural science was replaced with rigid theology. This appendix proposes the use of forensic tools to detect narrative manipulation and symbolic inversion in scripture. Rome’s enduring success was based not on invention, but on strategic appropriation and rebranding of older truths.

Appendix VI - Moses as Osiris

The biblical figure of Moses is analysed as a mythic duplicate of Osiris, sharing motifs such as river birth, exile, divine law, and symbolic resurrection. Egyptian ritual drama had already established this narrative centuries before the Torah was written. The appendix argues that Judaism adopted and recast Egyptian myth to serve a new tribal narrative. Osiris becomes Moses not through coincidence, but through literary substitution and symbolic reuse. The Bible did not invent the Moses story but retrofitted an Osirian template to establish a new identity and priesthood. This reframing allowed Judaism to claim cosmic authority based on older myths it did not originate.

Appendix VII - Huxwelled: The Manipulation of the Masses

The term “Huxwelled” combines insights from H. G. Wells, George Orwell, and Aldous Huxley to describe a society shaped by psychological manipulation. Through a mixture of pleasure, distraction, and surveillance, modern institutions control thought without the need for force. The appendix argues that this kind of control began long before the 20th century, dating back to the consolidation of religious orthodoxy in the 7th century. Consensus is achieved not through truth, but through repetition, ritual, and symbolic confusion. Mass media functions as a modern priesthood, administering doctrine through screens instead of pulpits. The result is a culture that has lost access to symbolic literacy and cannot see the structure of its own programming.

Appendix VIII - The Drift into China

China’s early symbolic systems reveal surprising parallels to Mesopotamian and Anatolian culture, suggesting an eastward Drift of cosmological ideas. Dragon myths, twin-peaked mountains, and axis rituals all reflect a shared symbolic grammar. Phonetic echoes and ritual calendars further support the argument for a Eurasian cultural memory that predated formal trade routes. China did not merely develop in isolation but absorbed and transformed westward traditions. These patterns indicate a pan-Eurasian Drift of mythic science and cosmology. The appendix adds China to the map of symbolic diffusion that originated around the Danube.

Appendix IX - The 2,160-Year Rhythm of History: Rise, Apex, and Decline

Human civilization rises and falls according to a 2,160-year cycle, which corresponds to the precessional shift of the zodiac. Each age such as Taurus, Aries, or Pisces reflects a different symbolic regime and cosmological structure. Societies thrive when their myth, architecture, and law align with the cosmic rhythm. As alignment fades, entropy and confusion increase until symbolic collapse resets the cycle. The Gospel age of Pisces is framed as the end of a distorted pattern rather than a divine conclusion. The appendix offers the zodiacal clock as a tool for understanding cultural rise and decline.

Appendix X - Return of the Djedi: The Westcar Story

Djedi, a magician in the ancient Westcar Papyrus, is portrayed as a bearer of cosmic knowledge and harmonic balance. He possesses powers such as restoring the dead and knowing sacred temple secrets, which symbolize his alignment with truth and structure. The Djedi is not a class of priesthood, but a singular archetype of coherence during dynastic transition. The appendix links this figure to the modern Jedi as a symbolic echo of the Egyptian Djedi. Rather than fantasy, Djedi represents the embodied wisdom of Drift Culture preserved in storytelling. His tale acts as a vessel for remembering how knowledge once lived in persons, not books.

Appendix XI - The Geometry of Eternity

Sacred geometry functioned as the original metaphysical grammar of human experience. Egyptian monuments encoded spirals, golden ratios, and infinite loops as tools for expressing continuity and measure. The twisted flax glyph, which resembles an infinity symbol, held mathematical and cosmological meaning. Geometry served not only architectural needs but also ritual, music, and seasonal alignment. This appendix argues that symbolic forms are not decoration but instruments of resonance. Eternity was not a concept of time, but a quality of proportion.

Appendix XII - The Wisdom That Was Already Ours

Ancient wisdom was never lost, only misattributed or rebranded under theological control. Myth functioned as a delivery system for shared truth that was experiential and ecological. Teachings associated with Jesus had circulated centuries earlier in multiple traditions. Scripture did not invent them but adopted and framed them as exclusive revelation. This appendix reclaims wisdom as ancestral, collective, and observable in nature. Truth was never hidden, it was only overwritten.

Appendix XIII - Natural Science as Myth: The Egyptian Foundation Stone

Egyptian myth encoded a working system of natural science, based on solar, hydrological, and harmonic cycles. Gods represented principles such as light, growth, decay, and rebirth, not beings with personalities, but forces in symbolic form. The Masonic significance inherent in the geometry of glyph, myth and play is explored through the tale of Hippolytus. The Foundation Stone served as a marker of alignment between spirit and matter. Temple rituals reflected agricultural rhythms and cosmic geometry. Later interpretations confused these symbols for superstition or theology. The appendix restores myth as the original science of life. The glyphs for Ptah and Hotep - square mat/infinity sign/raised life sign reveal geometric and architectural logic which ultimately has become lost in translation; emerging in the Bible as God and Jesus. Imhotep is revealed as Ptah in reverse - the return to peace/order from the cycle of Prime Causation/disorder; thereby revealing Ptah/Atum as the original ‘prince of peace’, Great Architect/Craftsman/messiah and eternal Creator known as YHWH..

Appendix XIV - The Perfection of Measure

This appendix presents extensive evidence that ancient measurement systems were based on harmonic principles. Ratios from the Pythagorean tetractys, often credited to Greece, appear in Saqqaran religion and early Egyptian architecture. Units of length, sound, and time were all derived from sacred geometry. As culture secularized, these systems became abstract and lost their symbolic meaning. The author incorporates this knowledge into the IXOS framework to demonstrate the coherence of original measure. Simple transforms of the tetractyc equilateral triangle to right angled stretches the hypotenuse to a ratio with a remarkable alignment to modern physics’ understanding of Relativity and Time Dilation.

Appendix XV - Pharisees: the ‘Seers of Phi’

The Pharisees are reconsidered not as rigid legalists, but as an esoteric class once associated with phi, the golden ratio. Linguistic parallels connect their name to terms for fire, pyramid, and the Egyptian Per-aa, or Great House - from which we derive our word Pharaoh. They may have preserved sacred geometry and temple knowledge before their role was rewritten. The shift from science to dogma obscured their original purpose. This appendix reconstructs the symbolic profile of the Pharisees from hidden fragments. Their transformation reflects the broader drift from wisdom to orthodoxy.

Appendix XVI - The IXOS Apocryphon

IXOS is presented as a unifying model that brings together myth, geometry, language, and cosmic rhythm into a single symbolic system. It synthesizes themes from the entire book to offer a method for reinterpreting culture and history through harmonic principles. IXOS does not function as belief but as a framework for recovering measure, proportion, and memory. The system re-establishes myth as encoded science and language as structured resonance. The Apocryphon acts as a lost chapter of Drift Culture reassembled. It closes the work with a call to restore not just truth, but the tools for reading it.

PREFACE

Welcome to the first draft of a book that represents a culmination of my life-long exploration of religion: its origins, its appeal, and, most profoundly, the divisions it creates. It is this division that has always intrigued me. How is it that something as seemingly benign as a Bible-based religion - one that preaches love and unity - has led to the surrender of our most sacred ideals, often spiralling into conflict?

In this work, I focus not on spirituality or the cultural cohesion that religion can foster, but on the imposed, dogmatic forms of religion. It is these forms - shaped by historical manipulation - that I define as religion. My stance is not against the spiritual teachings or profound insights contained within religious texts, but against the way these ideas have been distorted by external systems to control and dominate.

The ability to engage with the sacred on a personal level requires first understanding where our beliefs come from and how they have evolved. Without this awareness, we risk surrendering our ability to think critically and discern the truths that lie beneath centuries of imposed dogma. When beliefs are inherited without scrutiny, it becomes easy to fall prey to systems designed to serve the vested interests of those who benefit from our submission.

Therefore, this book must be understood as anti-religious in the sense that it challenges the dogma that has obscured deeper, more authentic knowledge of the sacred. I believe that at its core, religion holds a profound transmission of wisdom and connection, one that is recoverable. This work is my attempt to restore that lost knowledge and bring it back into common understanding. To share my own, albeit amateur, perspective for the consideration of others has been a long time goal which I began decades ago, and never got round to completing.

I will continue to refine and expand upon this work through my website at ivanfraser.substack.com, where you will find updates, as well as hyperlinked data to both internal and external sources. This platform also includes essential embedded videos that complement the material in this book. As such, my website should be considered the more comprehensive, up-to-date version of this work, while the pdf version of the book serves as the greater part of the textual evidence. The complete book incorporates articles that have not been labelled in this series as part of the work. The pdf version will include the contents as presented above, whereas the website will follow a slightly different structure.

This work is presented as a two-part exploration. The main body of the chapters offers a sweeping 6,000-year narrative, tracing the origins of myth and culture up to the early Common Era, when these foundations began to take the form of what we now recognise as religion. However, it is the Appendices that provide much of the supporting evidence, offering the detailed background necessary to contextualise and validate the arguments made in the chapters. I urge readers to engage with these appendices as an integral part of the entire work. Only by doing so can the chapters achieve the full perspective and cohesion required to understand the vast body of evidence, which presents a rarely considered but well-supported view of the history of religion. When established consensus is challenged by conflicting data, it is not only appropriate but essential to revise our understanding.

Note on style: In order to complete the full write-up of my extensive notes and to provide as much evidence as each section requires, I have had to lean on AI for assistance. And although my writing style can be somewhat archaic at times, there is a certain formal and formulaic style which the AI engine employs which is not quite in sync with my own. Without this new technology it would have been impossible to compile this draft in such a short time, however, whilst also working on other projects. This method also enabled new realisations along the way, which I have incorporated into the text. It therefore remains for me to apologise to the reader if you find some of the chapters somewhat tediously and drily presented in parts. What remains is for me to extensively revise and rewrite this work later. But the main framework is now completed.

Introduction: Orion and the Lost Structure of Truth

For centuries, history has been presented as a line of separate civilisations and distinct religions, each with its own origins, beliefs, and sacred figures. This is the framework most of us inherit - Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, the Bible, and later Christianity - all treated as discrete compartments. Yet the deeper we look, the more this consensus falters. Patterns recur across continents and millennia: the same symbols, the same ratios, the same stories in different dress. Something older runs beneath them all.

The axis of that older structure is Orion.

From prehistory onward, the constellation of Orion shaped myth, measure, and psychology. It appeared not only as a hunter in the sky, but as a living axis - the bridge between stars and stone, above and below. Its pattern guided settlement, temple-building, and the first languages of symbolism. It became the unifying key of geometry, proportion, and sacred kingship. Orion was never local. It was global memory.

This work is not intended as a survey of every human advance across deep prehistory. Sites such as Jericho, Göbekli Tepe, and Çatalhöyük demonstrate that early communities possessed intelligence and ingenuity equal to later peoples, and that complex settlements existed long before consensus allowed. They stand as reminders that cultural breakthroughs could occur independently and much earlier than once believed. Yet they are not our central concern here. The scope of this book is narrower: to trace the markers that directly informed myth and religion, and to restore Orion to its place at the axis of that symbolic structure. The purpose is not to write anthropology, but to show how Orion’s pattern shaped the emergence of global myth, measure, and belief.

What happened to that memory?

Here lies the fracture. Ancient cultures had already intuited what later became known as Pythagorean mathematics - the recognition of harmony, ratio, and proportion as the organising principles of life and cosmos. Phi and the tetractys were not abstract numbers; they were sacred forms seen in rivers, spirals, pyramids, and the order of the stars. The goddess was equally central - Isis, Inanna, Minerva, and countless other names embodying the field, the womb, the water, the matrix in which ratio takes form. Together, these were not “beliefs” but structural truths.

Over time, this natural clarity was overwritten. Ratio was encrypted into religion. What had been geometry became theology. What had been phi became “the Word.” Symbols of the goddess were denigrated, reduced, or recast as subordinate - the veiled Mary rather than Isis enthroned. The balance of male and female, of form and field, was severed, leaving a patriarchal god enthroned as the sole authority. The sacred mathematics became hidden within liturgy, architecture, and scripture - available only to initiates or priestly elites, while the laity were given dogma in its place.

This is the deception at the heart of history.

Return of the Storm God is a multidisciplinary investigation into that deception. Drawing on archaeology, etymology, cultural belief systems, astronomy, and myth, it restores Orion to its rightful place at the axis of civilisation. In doing so, it reveals how sacred ratio and feminine archetypes were systematically removed from memory, leaving us with fragments and distortions. The journey begins in the Danube basin with the Vinča script and proto-writing, follows the drift into Mesopotamia and Egypt, and traces how axis, measure, and symbol were transformed into theology.

The implications are profound. To recognise Orion’s pattern is to reappraise everything we thought we knew about religion and history. The myths of Egypt and Sumer, the geometry of the pyramids, the cult of kingship, even the Gospels and the figure of Jesus - all stand revealed as parts of a far older structure. What emerges is not random myth-making, but a coherent system of sacred proportion that was deliberately obscured.

This book restores that structure. It does not offer a new dogma, but recovers what was always there in nature: the spiral of life, the axis of the heavens, the balance of water and light. In tracing how these truths were hidden - by encryption into theology and by the suppression of goddess symbols - it confronts consensus history with its greatest blind spot.

The Storm God returns as more than a myth. He is the key to unveiling the architecture of culture, consciousness, and cosmos - and with him comes the chance to reclaim what was always ours: the recognition that nature, ratio, and field are the true foundations of civilisation.

The full completed first draft is freely available as a pdf, if you would prefer to have it in your archives. Please feel free to network it - all my work is free of charge or obligation: Return of the Storm God first draft pdf download

Chapter 1 - The Birthplace of Writing? The Bedrock of Myth?

Introduction

The origins of writing, symbolism, and early civilization have long captivated scholars, revealing tantalizing glimpses of humanity’s earliest steps toward complex culture. Among the many ancient scripts and signs unearthed from the earth, few possess the enigmatic allure and profound antiquity of the Vinča script - an intricate system of symbols etched onto pottery, tablets, and figurines in the Neolithic Danube basin.

Dated securely between 5500 and 4500 BCE, the Vinča script predates the more widely recognized cuneiform writing of Sumer by over a millennium, yet remains largely absent from mainstream historical narratives. Its undeciphered signs offer a whisper from a distant past - a coded message from a world where human ingenuity first began to reach beyond the spoken word and into the realm of abstract expression.

This work begins with a meticulous examination of the Vinča script and culture, laying the foundational stone for a broader inquiry. It invites the reader to embark on a journey that starts here, in the river valleys and mineral-rich soils of Southeastern Europe, but does not end there. As the story unfolds, what begins as a study of proto-writing and early metallurgy will expand into a panorama of shifting civilizations, mythic archetypes, and cosmic patterns that ripple through time and space.

Patience will be required. The earliest chapters are necessarily measured, scholarly, and detailed - yet within them lie the seeds of revelations that will challenge conventional history and illuminate the very architecture of human culture and consciousness.

For those willing to delve deeply and follow the threads, this path promises not only understanding but transformation. What appears at first as discrete symbols on clay will gradually reveal itself as part of a vast and intricate tapestry - a story as much about the stars above as the earth beneath, as much about the human spirit as the hands that shaped these ancient signs.

It should be stressed again that this is not an attempt to catalogue every settlement or advance across deep prehistory. The focus remains on those symbolic and structural markers that fed directly into the myths, measures, and religious systems later built around Orion. Sites like Vinča are treated here not as isolated curiosities of anthropology, but as part of the chain of evidence showing how a global symbolic grammar emerged and was later obscured.

Exploring the origins of human symbols in the fertile valleys of the Danube basin - where clay, fire, and meaning first converged to shape the dawn of culture and myth.

Perhaps before words formed sentences, before alphabets arranged meaning, early humans inscribed their first marks on clay and stone - symbols born from necessity, observation, and the human urge to communicate beyond speech. The Vinča script, unearthed in Southeastern Europe, offers a rare glimpse into this primordial world - a place where the practical and the sacred intertwined.

This chapter embarks on a journey through the oldest known system of symbolic signs, asking profound questions: Was this truly the birthplace of writing? And could these ancient markings be the foundation upon which the world’s myths, including the very stories that define us, were built?

The answers lie not just in the signs themselves, but in the rivers, the minerals, the rituals, and the communities that birthed them.

The Vinca Script - The Earliest Known Writing System?

The Vinča script, also known as the Old European script, represents what may be the earliest known attempt by humans to encode meaning into a system of visual signs. Dated securely between 5500 and 4500 BCE, it predates Sumerian cuneiform by over a thousand years, yet remains largely absent from mainstream historical narratives. This foundational article outlines the discovery, structure, context, and current scholarly debate surrounding the Vinča inscriptions, strictly within the limits of confirmed archaeological evidence.

Discovery and Chronology

The script takes its name from the site of Vinča-Belo Brdo, a Neolithic tell (meaning mound) near Belgrade, Serbia, excavated in the early 20th century by Miloje Vasić.

Image 1: Vinča-Belo Brdo Archaeological Excavation Site - one of the core settlements of the Vinča culture. (By Unknown author - Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of Serbia, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74153351)

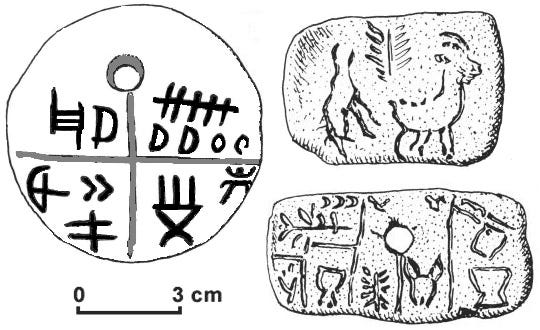

However, the most significant push in global awareness came with the 1961 discovery of three inscribed clay tablets at Tărtăria, Romania, by archaeologist Nicolae Vlassa. These tablets were found in a ritual context, buried with a female skeleton and various ceremonial items.

Image 2: Tărtăria Tablets: The three inscribed clay tablets from Tărtăria, Romania - dating to approximately 5500–5300 BCE and key to understanding early symbolic communication. (By Mazarin07 - Own work & File:Kép 586.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=106065922)

Radiocarbon dating of associated organic material placed the tablets between 5500 and 5300 BCE. Further stratigraphic and material consistency across Vinca-culture sites from Serbia to western Romania confirms the broader script corpus dates from roughly 5500 to 4500 BCE.

Corpus and Distribution

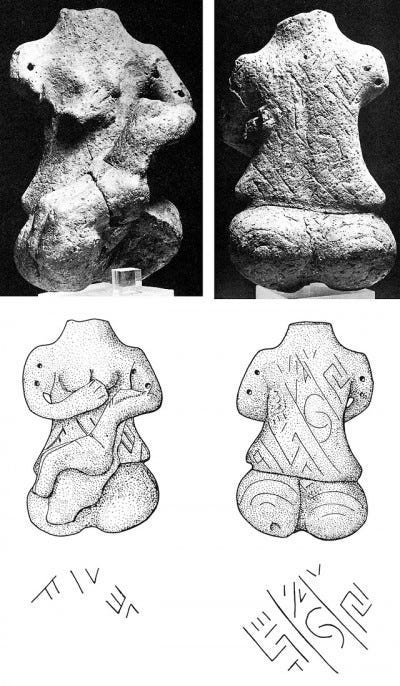

Over 700 inscribed objects bearing Vinča symbols have been found across Southeastern Europe, particularly in modern-day Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Hungary. Most inscriptions appear on ceramic vessels, spindle whorls, figurines, and tablets. These signs are typically incised prior to firing, often in isolation or in small groupings, and are non-randomly positioned - frequently on the shoulders of pots or the foreheads and torsos of figurines.

Script Characteristics

The signs themselves comprise a set of abstract and geometric motifs: X-shapes, ladder forms, chevrons, spirals, combs, crosses, and meanders. Some signs appear repeatedly across hundreds of kilometres, and there is limited but real evidence of sign combinations recurring in specific sequences, hinting at a semantic or syntactic function. Notably, the same symbols are not found as part of decorative motifs, and are typically absent from the utilitarian wares of the culture.

Image 3: Neolithic Pottery with Vinča Symbols: Neolithic ceramic vessel bearing Vinča symbols - illustrating the geometric motifs incised prior to firing. (By Nikola Smolenski - Own work - on the basis of available illustrations and photographs., CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70042)

Unlike pictographic scripts that evolve into syllabaries or alphabets, the Vinča symbols may represent an ideographic or logographic stage - or a ritual code designed more for function than phonetics. Current scholarship is divided between seeing it as a form of proto-writing and as a fully symbolic system whose content may have been understood within a ritual or priestly class.

Academic Debate and Consensus

In the 20th century, the dominant view saw these signs as decorative or symbolic but not linguistic. That view has shifted. Scholars like Marija Gimbutas argued for a symbolic, religious script used in matrifocal Neolithic cultures. Harald Haarmann and others have supported this with comparative statistical analyses showing structured repetition and patterning. While no bilingual key exists, the weight of current opinion favours defining the Vinča symbols as proto-writing - a formal system encoding non-random meaning, even if not a spoken language.

Caution must be applied, however, regarding claims of direct links between Vinča and later scripts like Sumerian cuneiform or Linear A. While superficial similarities exist - e.g. in "comb" or "fishbone" motifs - there is no firm epigraphic or linguistic bridge.

Contextual Significance

The archaeological contexts of the inscriptions reinforce their potential importance. Many are found in graves, on cultic figurines, or near altars. Their placement suggests intentional use in ritual or identity-marking functions. The Tărtăria tablets, in particular, were not random objects but were clearly associated with ceremony and burial.

The Vinča script represents the oldest sustained system of symbolic signs yet discovered. While undeciphered and still debated in function, it stands as concrete evidence of complex symbolic communication in Southeastern Europe long before the dawn of historical writing in Mesopotamia or Egypt. This is not myth; it is stratified, datable, material fact. Any meaningful inquiry into the origins of language, symbolism, and early spirituality in Eurasia must begin here.

Symbol and Settlement - The Danube Basin as Cradle

Following the establishment of the Vinca script as the earliest known system of symbolic signs, we now examine the cultural and environmental basis that enabled such a sophisticated symbolic language to emerge. The Danube basin, particularly in the regions of modern Serbia and Romania, was not only the geographic setting for the Vinca culture - it was also an ecological and mineralogical cradle that provided the necessary conditions for cultural complexity to thrive.

Hydrography and Settlement

The Vinca culture developed along major tributaries of the Danube River, including the Morava, Tisa, and Olt rivers. These rivers provided a stable water source, natural transportation routes, and fertile floodplains ideal for early agriculture. Nearly all Vinca sites are located within a short distance of permanent watercourses.

Images 4a and 4b: Map of the Danube Basin and Vinča Culture Distribution: Map showing the spread of the Vinča culture across the Danube basin in Southeastern Europe. (By WikiEditor2004 - Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=89228044)

Evidence from sites such as Vinča-Belo Brdo, Tărtăria, and Divostin suggests long-term settlement, often on elevated terrain near riverbanks, with sophisticated architecture including daub-walled houses, communal planning, and dedicated ritual zones.

This stable hydrological base enabled population growth, surplus production, and the emergence of specialized crafts - conditions typically associated with early writing systems.

Water was not simply a practical asset - it was the precondition of all life. Every Vinca settlement began at water’s edge, and every act of survival - agriculture, metallurgy, burial, birth - depended on it. In this sense, water was not only central to physical life, but to the symbolic imagination: the earliest signs were incised near thresholds, rims, and flows, echoing the dynamics of water. Over time, these dynamics likely entered sound and language itself. If we are to understand the emergence of symbolism in Neolithic Europe, we must begin where the culture itself began - at the river.

Mineral Resources and Cultural Development

One of the most significant features of the Vinca area is its mineral wealth, particularly in copper and salt. Excavations at Rudna Glava and Ai Bunar confirm the existence of organized copper mining as early as 5000 BCE. This predates large-scale metallurgy in Mesopotamia by centuries.

Image 5: Early Copper Mining Site - Rudna Glava: Archaeological remains at Rudna Glava, Serbia - evidence of organized copper mining dating back to 5000 BCE. "(Adapted from Radivojević, T. (2007), "Evidence for Early Copper Smelting in Belovode, a Vinča Culture Site in Eastern Serbia," MSc Thesis, UCL Institute of Archaeology)

Salt, essential for food preservation and trade, was available from natural brine springs such as those at Turda and Ocnele Mari. These mineral sources provided both the material and economic basis for regional networks and exchange systems. The surplus and specialization resulting from these industries likely played a direct role in the development of a symbolic system to mark ownership, record transactions, or conduct ritual codification.

Place Names and Phoneme Roots

While speculative linguistic analysis must be handled cautiously, scholars have noted that many place-names in the region preserve root phonemes such as kar, gar, kal, gal, val, and dur, which recur in various Eurasian hydronyms and toponyms associated with early settlement zones. These may reflect archaic naming conventions based on geological features, water sources, or mineral characteristics.

That said, no direct, datable linguistic link between Vinca script and these toponyms has been proven. The correlation remains suggestive but must not be overstated.

Settlement Patterns and Cultural Continuity

The consistency in pottery styles, house construction, burial customs, and symbolic motifs across Vinca sites indicates a strong degree of cultural cohesion over centuries. This cultural continuity, centred in riverine landscapes rich in life-sustaining resources, provided the foundation for symbolic stability - a prerequisite for the development of recognizable sign systems.

It is also notable that many signs appear on everyday objects like spindle whorls and vessels, suggesting that the symbolic language was embedded in domestic and social practices rather than isolated to elite or religious functions.

The emergence of the Vinca script was no accident of time or place. It arose within a matrix of fertile rivers, accessible metals, vital salts, and long-settled communities - a rare convergence of environmental and cultural resources. This context provides a firm empirical basis for understanding how and why the first known European writing system took form not in isolation, but in deep and dynamic relation to its land, its water, and its people.

Structure, Repetition, and Pattern - Reading the Vinca Script

With the cultural and ecological basis of the Vinca settlements established, we now turn our attention to the internal structure of the Vinca script itself. This includes the catalogue of signs, their repetition across space and time, and the patterns of their use - all critical to determining whether these signs constitute a meaningful system rather than random or purely decorative markings.

Inventory and Classification of Signs

Across the corpus of over 700 known inscribed artefacts, researchers have identified roughly 30 to 50 distinct symbols, depending on how variants are categorized. These include:

X-shapes

Ladder or comb motifs

Zigzags and meanders

Crosses

Loops, circles, and spirals

Chevron patterns

Rectilinear grids

The signs are geometric and abstract, bearing no obvious pictorial resemblance to objects, animals, or people. They are incised before firing, often with precision.

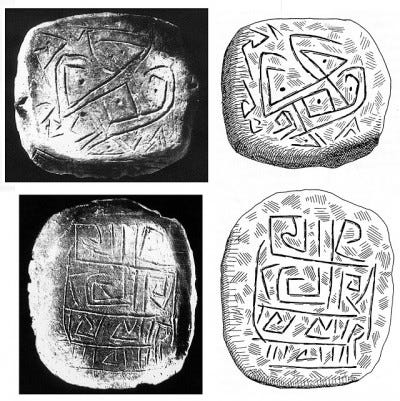

Image 6: Common Vinča Symbolic Motifs: Common Vinča symbols including spirals, crosses, and chevrons found on Neolithic artefacts. (From Sacred Script: Ancient Marks from Old Europe by Cari Ferraro: )

Repetition Across Sites

Identical or near-identical symbols have been found across multiple sites, sometimes separated by hundreds of kilometres. For example, a particular ladder-like glyph appears on tablets at Tărtăria and on ceramics at Vinča-Belo Brdo. Another comb or rake-shaped sign recurs at Uivar and Banjica.

This cross-regional repetition implies shared meaning or cultural standardization. Decorative patterns tend to be diverse and locally variable; standardized sign repetition over distance and time strongly supports the hypothesis of a symbolic or linguistic function.

Position and Orientation

Signs are often placed in consistent locations: on the shoulder of pots, across the top of tablets, on the head or chest of figurines, or on the base of spindle whorls. The orientation of the signs is consistent within object categories. Inscriptions are sometimes aligned in rows or arcs, and in rare cases in columns. This ordering suggests non-random placement and possibly rule-based structure.

Combinatorial Patterns

Some artefacts contain sequences of two or more signs in repeated orderings. A cross followed by a triangle may appear in the same configuration on multiple spindle whorls, for example. Though no definitive grammar has been identified, the frequency of these pairings exceeds what would be expected from decorative chance.

At least one researcher (Harald Haarmann) has proposed that the frequency distribution of Vinca signs matches what one would expect from a functioning script. He notes that certain signs occur frequently in leading positions, while others appear more often in medial or final positions - a feature common to known scripts.

Purpose: Record-Keeping, Identity, or Ritual?

Interpretation remains open. Proposed functions include:

Property or maker's marks (identity tags)

Proto-records of trade or exchange

Ritual or clan symbols

Mnemonic or calendrical tools

None of these are mutually exclusive. The placement on domestic items (e.g., spindle whorls) hints at daily usage, while the presence on grave goods and figurines implies ceremonial significance.

Cautions and Limitations

No bilingual or multi-lingual artefact (like a "Rosetta Stone") has yet been found. The symbols do not correspond one-to-one with any known later writing system. There is no consensus on phonetic value, and all proposed decipherments remain speculative.

Still, the combination of limited sign inventory, pattern repetition, consistent placement, and spatial-temporal distribution supports the classification of the Vinca symbols as a proto-writing system.

The Vinca signs are not arbitrary. Their internal structure - in terms of repetition, placement, and sequencing - reflects a coherent and culturally embedded system of symbolic communication. While not yet deciphered, they bear the hallmarks of a functioning sign system, embedded in both the ritual and the practical lives of Neolithic Southeastern Europe. Their purpose remains enigmatic, but their intent is now unmistakable: these marks meant something.

The Tărtăria Tablets - Ritual or Record?

Among the most iconic artefacts associated with the Vinca culture are the three small clay tablets discovered in 1961 by Romanian archaeologist Nicolae Vlassa at Tărtăria, in the Transylvanian region of Romania. These objects remain pivotal in the debate over the origins and purpose of Old European writing systems. Their context, content, and the questions they raise lie at the very core of early European symbolic communication.

Discovery Context

The tablets were found in a ritual pit grave alongside the remains of a mature female skeleton, two clay figurines, and a variety of other ceremonial items, including a shell bracelet and fragments of burned animal bone. The burial was not typical for the broader Vinca culture, leading some to interpret the individual as a priestess or person of special ritual significance.

Associated carbon-dated material places the burial at approximately 5500 to 5300 BCE. While there has been academic debate regarding the intrusion of the tablets into later strata, most archaeologists now accept them as authentically Neolithic.

Description of the Tablets

Each of the three tablets is approximately 4 cm in diameter and displays a distinct configuration of incised symbols:

One tablet is rectangular and features a grid-like arrangement of signs, including repeated X-shapes and cross-hatching.

Another is circular and includes a central figure resembling a stylized anthropomorphic form or solar cross.

The third tablet, also circular, is more abstract, with lines, dots, and crescents in a layout resembling a schematic or cosmological diagram.

The signs were incised before firing, and all three tablets are unbroken and well preserved.

Interpretative Frameworks

Multiple interpretations have been advanced, falling into several main categories:

Proto-Writing or Early Script: Some scholars argue that the tablets reflect a non-phonetic system of proto-writing used for ritual, calendrical, or administrative purposes.

Ritual or Religious Artefacts: Given the burial context and symbolic content, others argue the tablets were ritual items, possibly encoding cosmological or mythological knowledge rather than transactional information.

Trade or Property Marks: A minority have proposed that the symbols could denote ownership, commodity records, or exchange tokens, though the context weakens this hypothesis.

Forgery Theory (Now Rejected): In the early years after the discovery, some critics alleged that the tablets were modern forgeries. This theory has been effectively discredited based on material analysis, patina consistency, and stratigraphic congruence.

Comparative Evidence

Some motifs on the tablets resemble signs found in later Mesopotamian scripts, such as the Uruk IV tablets from Sumer (c. 3300 BCE). These include nested chevrons, crosses, and grid forms. However, no direct developmental pathway has been confirmed.

The strongest parallels remain internal - the same signs appear on ceramics and figurines across the Vinca region, reinforcing their authenticity and embedding them within a broader symbolic system. The repetition of sign sequences between the tablets and other artefacts strengthens the case for intentional codification.

Function and Meaning

Without a bilingual key or continuity into later known scripts, definitive interpretation remains elusive. However, several plausible functions are consistent with archaeological context:

Mnemonic aids for ritual recitation or seasonal observation

Cosmological diagrams representing celestial or agricultural cycles

Tokens of spiritual or communal authority

The anthropomorphic and circular designs hint at mythic-symbolic use, likely tied to the role of the buried individual.

The Tărtăria tablets are the most compelling individual artefacts in the Vinca corpus. Their early date, preserved condition, and ritual context make them the strongest single piece of evidence for structured symbolic thought in Neolithic Europe. Whether or not they constitute "writing" in the strict sense, they clearly reflect an intention to encode and preserve meaning - a goal shared by all early literate traditions. In this sense, they are both a record and a rite.

A note on the significance of Transylvania:

Whilst, Transylvania is most widely recognised as the fictional home of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, it would be reasonable to say that it is one of the most historically significant areas in world history, for its contributions to cultural development.

The broader Danube basin - including parts of modern Serbia, Bulgaria, and Hungary - also played a crucial role in the rise of the Vinča culture; major sites like Vinča-Belo Brdo (Serbia) and Divostin contributed significantly to the region’s cultural landscape.

However, Transylvania’s enduring cultural legacy has persisted since that time. Transylvania’s resources - salt, copper, gold, silver, and iron - were unparalleled in the region. Salt springs at Turda and Ocnele Mari, and early copper mining at sites like Ai Bunar, provided the economic surplus and trade networks that underpinned cultural innovation.

This mineral wealth not only fuelled local development but also made Transylvania a critical hub in wider European trade and cultural exchange, from the Neolithic through the Roman era and beyond.

The region’s stable river valleys (notably along the Mureș and Olt) and fertile plains supported large, long-lived settlements with sophisticated architecture, communal planning, and dedicated ritual zones - conditions ideal for the emergence of symbolic communication.

The ritual context of the Tărtăria tablets, including their burial with a probable priestess, highlights Transylvania’s role as a spiritual and ceremonial centre. The consistency of pottery styles, symbolic motifs, and burial customs across Transylvanian sites points to a high degree of cultural cohesion and continuity, further reinforcing its central role in the region’s development.

Symbolism of Sound and Substance - Interpreting the Vinca Signs

Having examined the structure and core artefacts of the Vinca script, we now address the signs themselves in symbolic and semiotic terms. While no phonetic values have been reliably assigned, certain patterns suggest a relationship between sign morphology and core cultural concepts, including natural elements, spatial orientation, and possibly even proto-vocalic sound roots. This section explores such interpretive pathways cautiously, remaining tethered to recurring empirical motifs.

Geometric Forms and Conceptual Resonance

The visual repertoire of Vinca symbols draws heavily on fundamental geometric structures: the cross, the circle, the chevron, the spiral, the ladder, and the meander. Across cultures, such forms are rarely neutral. Even without phonetic decoding, their recurrence in contexts of death, ritual, and domestic function signals their symbolic weight.

For example:

The cross (X or +) may represent intersection, cardinal directionality, or sacred centrality.

The spiral appears universally as a symbol of growth, motion, and possibly seasonal or cosmic cycles.

Ladder and comb motifs may imply progression, measurement, or tally.

These interpretations, while analogical, are grounded in comparative archaeology, not mysticism.

Semantic Fields and Contextual Placement

The consistent placement of signs on ritual figurines, particularly on the chest, head, and abdomen, implies a body-map logic: signs may correspond to conceptual "zones" such as intellect, breath, reproduction, or spirit. This reinforces the likelihood that Vinca signs encoded not merely transactional but metaphysical or cosmological meaning.

Pottery inscriptions often cluster near vessel openings or junctions - locations of flow, containment, or transition. This placement may reflect symbolic associations with the function of the vessel and, by extension, with notions of nourishment, passage, or offering.

Sound and Root Morphology: A Cautious Inquiry

While the Vinca script has not been deciphered, certain proto-linguistic hypotheses suggest that symbolic systems may begin with associations between phonemes and material or elemental referents. Scholars have pointed to recurrent roots in early Eurasian hydronyms such as:

· kar / kal (stone, light, fortress, height)

· gar / gal (soft “ge” forms often associated with flowing water or gel-like substances that carve and shape the harder “kal” forms)

· val / bal (water, white, flow)

· dur / tur (boundary, gate, crossing)

These roots appear extensively in place-names and river names across the Balkans and greater Eurasia. The phonetic consistency, particularly when related to rivers and settlement sites, suggests a very early symbolic relationship between sound, form, and elemental force.

The “soft ge” forms such as gar and gal can be understood as representing the dynamic, fluid, or gel-like aspects of water or other shaping substances that, over time, physically carve and shape the harder “kal” (stone or fortress) elements into form. This process metaphorically captures how the fluidity of water or other natural forces sculpts the solid earth - turning hard rock into shapes that bear symbolic or toponymic significance.

In some linguistic and symbolic traditions, this dynamic is further represented by the transformation of these root forms into related concepts such as the “cowl” - a protective or enveloping form - emphasizing the interplay between hard structure and fluid containment, boundary and flow.

Understanding this layered phoneme-semantic evolution helps elucidate how early peoples encoded their intimate relationship with the landscape and natural forces into language and symbols, potentially reflected in the Vinča script and later toponyms.

However, no direct evidence yet ties these roots to specific Vinca signs. Any correspondence remains circumstantial and must be treated as hypothesis, not conclusion.

Comparative Semiotics: Parallels Without Assumption

While parallels between Vinca motifs and those in later Sumerian, Anatolian, or Aegean systems are often invoked, no epigraphic bridge has yet been proven. Nonetheless, recurring symbolic forms such as crosses, nested chevrons, and meanders suggest a shared repertoire of signified meanings associated with life, death, time, and boundary.

Though undeciphered, the Vinca signs operate within a meaningful symbolic architecture. Their geometry, placement, and ritual context suggest more than aesthetic intent. They engage conceptually with ideas of direction, transition, substance, and possibly sound - forming a visual lexicon of early metaphysical grammar. Still, until direct correspondences can be established, any deeper reading must remain provisional. The evidence suggests intent, coherence, and cultural embedding - not yet language, but the preconditions of one.

Part 6: Early Diffusion? Vinca Motifs and Aegean-Anatolian Parallels

As we move deeper into the study of the Vinca symbolic system, it becomes essential to ask whether its motifs exerted influence beyond the Danube basin, particularly into Anatolia and the Aegean. While claims of direct transmission to later scripts like Linear A or B remain unproven, there is a pattern of geometric and ideographic similarity across cultures from the late Neolithic into the Bronze Age that invites cautious comparative analysis.

Chronological Boundaries and Archaeological Horizons

The Vinca script dates from roughly 5500 to 4500 BCE. By contrast, the earliest signs of writing in Anatolia and Crete (e.g. pre-Linear A, proto-Cretan pictographs, or Cycladic incisions) do not appear until 3000 BCE or later. This leaves a chronological gap of at least 1,000 years, filled by numerous cultural transitions.

While no inscribed object has yet been found that bridges this temporal and geographical gap directly, there are suggestive patterns of symbolic continuity that deserve mention.

Shared Motifs: Comparison Without Conflation

Several Vinca signs recur in later Neolithic and Bronze Age symbolic contexts:

Double-axe (labrys): While iconic in Minoan Crete, its antecedents appear in schematic incisions in Southeastern Europe.

Meander or running spiral: Common in Vinca ceramics and echoed in later Cycladic, Mycenaean, and even Iberian material.

Ladder and comb motifs: Occur both in Vinca assemblages and in early Anatolian rock art (e.g., Çatalhöyük wall paintings and sealings).

These similarities may reflect a shared symbolic toolkit rather than direct script transmission. Many such motifs emerge independently across agrarian societies, often in connection with solar, seasonal, or calendrical symbolism.

Cultural Interchange in the Neolithic-Bronze Transition

Archaeological data confirms long-distance contact networks across the Balkans, Aegean, and western Anatolia during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods:

Obsidian from Melos found in the Balkans

Vinca-style ceramics in early Thessaly and Macedonia

Shared architectural techniques (e.g. tell settlements, plaster floors)

These exchanges support the plausibility of idea diffusion, even if not script continuity. Ritual practice, ceramic decoration, and possibly symbolic schemas may have moved along these networks.

Limitations of Comparative Epigraphy

Despite visual parallels, we lack:

A shared lexicon or phonetic system

Bilingual or multilingual artifacts

Clear lineages of symbolic evolution

Linear A and B, while ideographic in origin, bear structural differences from Vinca signs and appear to reflect independent development within the context of Minoan and Mycenaean administrative needs.

Conservative Hypothesis

The most responsible current hypothesis is that while the Vinca signs did not directly evolve into the scripts of the Aegean or Anatolia, they may represent one branch of a broader Neolithic symbolic tradition in Southeastern Europe. This tradition could have influenced the symbolic literacy of later cultures indirectly through cultural memory or motif inheritance.

There is no proven scriptorial descent from the Vinca signs to the Aegean writing systems. However, archaeological and visual evidence suggests that a symbolic continuum may have existed across the Neolithic-Bronze interface in Southeastern Europe. The Vinca signs stand not as an isolated anomaly but as part of a larger symbolic ecology - a visual language of form and meaning that echoed, refracted, and possibly inspired parallel systems yet to be fully understood.

Root Phonemes and Hydronyms - Echoes in the Landscape

In exploring the broader implications of the Vinca script, researchers have noted intriguing correspondences between certain root phonemes and recurring place- and water-names (hydronyms) across Southeastern Europe and beyond. While no direct linguistic continuity has yet been confirmed between the undeciphered Vinca signs and these place-names, the phonetic clustering offers a tantalizing line of inquiry into the symbolic geography of early Neolithic settlement.

The Hydronymic Hypothesis

Hydronyms are among the most conservative elements of language. River names often persist for millennia, even after the original language is replaced. Scholars such as Theo Vennemann and Václav Blažek have argued that many hydronyms across Europe reflect a pre-Indo-European substratum with phonemic roots potentially traceable to early Neolithic languages.

• kar / kal / gar / gal: found in Carpathians, Karun (Iran), Kalamas (Greece) - including soft “ge” forms that often relate to flowing or shaping water or gel-like substances

• val / bal: found in Văleni, Valcea, Balaton, Volga

• dur / tur: seen in Durance, Durdevac, Turia, Turda

These roots frequently correspond with topographical features such as rocky outcrops, fortified hills, water sources, or white mineral exposures (salt, limestone).

Possible Semantic Associations

Although speculative, the recurrence of these roots across multiple linguistic and geographic contexts has led to proposed semantic fields:

• kar / kal: rock, fortress, elevation, light or shining surface

• gar / gal: flowing water, gel-like substance, soft shaping force

• val / bal: white, bright, water, floodplain, reflective

• dur / tur: boundary, crossing, passage, limit or gate

In some interpretations, these roots may have described key survival elements: defensible positions, accessible water, and navigable terrain. They may also reflect early ritual significance, with boundaries and shining stone or water sources marked as sacred or liminal.

Correlation with Vinca Settlement Patterns

While the Vinca script itself remains undeciphered, there is a plausible cultural correspondence between the location of Vinca settlements and sites bearing hydronymic roots of this type. Many Vinca sites, such as Tărtăria, Vinča-Belo Brdo, and Turdaș, lie near rivers or in valleys where names include "kar," "tur," or "val" phonemes.

This does not imply direct etymological descent, but it raises the possibility that the same environmental features which shaped the symbolic logic of the Vinca script also gave rise to place-names that preserved aspects of that worldview.

Limits of the Evidence

Critically, there is no secure way to map undeciphered signs to specific phonemes without a bilingual key or continuity into known written languages. Therefore, any suggestion that a Vinca glyph means "kar" or "val" is speculative. The connection here is one of cultural and environmental resonance, not translation.

Furthermore, many of these phoneme-roots are also found in Indo-European and later Uralic or Turkic place-names, complicating any attribution to Neolithic substrates.

The repetition of root phonemes such as kar, val, and dur in hydronyms across Vinca-adjacent regions does not prove a linguistic link to the script, but it does support the idea of a shared symbolic environment. These roots may encode relationships to stone, light, water, and movement that also underpinned Vinca cosmology and spatial logic. In this sense, the land itself may retain faint echoes of the signs once carved into its clay and bone.

Metallurgy and Sacred Function - The Smith and the Sign

The Vinca culture flourished in a region of significant mineral wealth, particularly in copper and salt. Beyond their economic implications, these resources appear to have had cultural and possibly sacred importance. This section explores the archaeological evidence for early metallurgy in the Vinca world, and how the act of extraction, transformation, and inscription may have intersected with symbolic and ritual life.

Early Metallurgy in the Vinca World

Archaeological evidence from sites such as Rudna Glava (Serbia) and Ai Bunar (Bulgaria) confirms that organized copper mining was underway in the Vinca cultural zone by at least 5000 BCE. This places Southeastern Europe among the earliest centres of metallurgical innovation in the world.

Vinca settlements such as Belovode have yielded slag, crucibles, and traces of smelting activities. Some copper artefacts - pins, awls, and beads - show signs of cold-working and annealing, marking the beginning of technological control over metal.

The Role of the Smith

In many traditional societies, the metallurgist is not merely a technician but a liminal figure - a mediator between the raw, chthonic powers of the earth and the structured world of human society. While there is no textual evidence from Vinca culture to confirm this status, the pattern is consistent with later Eurasian traditions.

The transformation of ore into tools and ornaments may have been viewed as alchemical or sacred, especially when linked to burial goods or ritual settings. If so, the smith may also have been a scribe - one who cut, incised, or impressed signs into copper or ceramic surfaces, embedding meaning in material.

Inscriptions and Tools

Many Vinca signs are found on clay spindle whorls, ceramic vessels, and figurines. While most of these are domestic in origin, some have been found in burial or ritual contexts. Notably, certain signs occur on tools or pendants that may have been worn by individuals with specialized roles.

Although inscriptions on metal are rare, their absence may be due to corrosion or recycling rather than lack of use. Copper is a difficult medium for long-term survival unless deliberately preserved.

Symbolic Implications of Ore and Fire

Copper extraction involves fire, transformation, and purification - all processes rich in symbolic content. The combination of clay, fire, and metal in Neolithic contexts suggests a convergence of material practice and conceptual abstraction.

The smith's control of fire and metal may have lent authority to their use of symbols - whether as personal insignia, ritual markings, or mnemonic codes. The act of inscribing a symbol into an object may itself have been seen as an invocation, protection, or dedication.

Sacred Economy and Exchange

Copper and salt were not merely local resources but commodities in regional trade networks. The marking of goods with signs may have served both practical and symbolic functions: to denote origin, ownership, value, or ritual condition.

If any of the Vinca symbols functioned as identifiers - clan marks, craft signatures, or ritual tags - it is likely that these first appeared in contexts of material exchange. The metallurgist, as a node in this network, would then also become a vector of early symbolic literacy.

Conclusion

The Vinca world of metallurgy was not merely technological but also profoundly symbolic and sacred. The smith may have been among the earliest to inscribe meaning into matter - to forge not only tools but signs. In doing so, the boundary between craft and cult, between function and form, became blurred. The smith, as shaper of both metal and meaning, stands as a likely candidate for the earliest literate actor in Neolithic Europe.

The emergence of metallurgy and ceramic craftsmanship in the Vinca culture reflects a deep and intimate technological synergy. Metallurgy - particularly copper smelting and casting - requires not only the extraction and refinement of ores but also mastery of heat control and refractory materials. Ceramics provide the essential medium for this transformation: crucibles, moulds, and furnaces must be crafted from carefully selected clays capable of withstanding intense temperatures without cracking or contaminating the metal.

This co-dependence implies that the development of advanced pottery techniques and kiln technologies must have evolved hand in hand with early metalworking skills. Where sophisticated metallurgy is found, archaeologists often uncover evidence of highly skilled ceramic production - standardized forms, fine finishes, and kiln-fired wares designed for both domestic and ritual use. In the Vinca cultural sphere, the evidence of specialized ceramic manufacture alongside early copper mining and smelting sites suggests artisans adept in multiple material crafts, combining practical knowledge with symbolic expression.

Beyond practical necessity, the co-evolution of metallurgy and ceramic work held profound cultural and symbolic significance. The smith and the potter are recurring archetypes in human mythology, representing the transformative power of fire and earth - the elemental forces that create and sustain civilization. The precision required to manipulate minerals for metal casting parallels the artistic and ritual precision embodied in ceramic decoration and symbolic inscriptions.

In Vinca settlements, the inscriptions on pottery - often placed near rims or handles - may reflect this dual identity: vessels as both utilitarian objects and carriers of symbolic meaning. As the craft of firing ceramics developed alongside metalworking, it is plausible that the symbolic systems encoded on pottery were reinforced by the ritual status of the smith and the potter, linking material mastery to social and spiritual authority.

Crucially, this intertwined evolution of metalworking and pottery was not based on abstract invention but grew organically from human observation and mastery of the natural world. Near Transylvania, the Vinca culture’s technological achievements reflect an intimate understanding of earth’s resources - minerals, clays, and fire - and how to manipulate them to serve practical, ritual, and symbolic purposes.

This co-evolution represents a foundational principle of early civilization: cultural myths, proto-writing, and technological innovation arise hand in hand from man’s empirical engagement with nature’s bounty. The mastery of mineral composites, heat, and form laid the groundwork for complex symbolic communication and ritual systems that would ripple outward, shaping the trajectory of Eurasian history and human culture.

Together, metallurgy and pottery shaped the technological and cultural landscape of Neolithic Southeastern Europe, providing the foundation for the emergence of complex symbolic communication, proto-writing, and ritual systems that would echo across Eurasia.

From survival necessities to myth is an expression of a natural evolutionary arc.

Where water was always the primary consideration in any culture’s survival, it formed the basis for early settlement and societal organization. Once a reliable water source was established, along with food and shelter, a localized ‘township’ could develop naturally, fostering a stable community attuned to its environment and able to exploit its bounty.

In this context, early metalworking in the Chalcolithic era emerged not as isolated innovation but as a direct outgrowth of regional cultural identity. A community required the certainty of a reliable supply of tools for harvesting and processing food, pottery to hold water and cook, and weaponry to defend the resources and security that sustained it.

Thus, the co-evolution of metallurgy and ceramic craftsmanship was inseparable from the fundamental human imperative to secure and manage water, food, and shelter - a synergy that shaped the technological, symbolic, and social foundations of Neolithic civilizations.

The fertile valleys of the Danube basin were not only the cradle of early symbolic writing but also a pivotal region for the emergence of viticulture—the cultivation of grapes and production of wine. Archaeological evidence from Southeastern Europe reveals that by the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, grapevines were deliberately cultivated in areas surrounding the Vinča culture, with pollen, seeds, and vine remains attesting to an ancient tradition of wine-making. This agricultural innovation was far more than a simple subsistence activity; wine and the vine carried deep ritual and symbolic significance, embodying themes of fertility, renewal, and social cohesion that would echo through mythologies across Eurasia.

The linguistic root “vin,” so often concealed or obfuscated in scholarly discourse, emerges as a key cultural marker within this context. Place names such as Vindolanda and the widespread Indo-European words for vine and wine trace their lineage back to this early cultural milieu, linking the physical cultivation of vines to a broader symbolic lexicon. This “vin” root thus acts as a thread weaving together the material, linguistic, and mythic fabrics of ancient European and Near Eastern civilizations. Recognizing this connection allows us to perceive early viticulture not just as an economic activity but as a profound cultural and spiritual symbol embedded within the communities that produced the Vinča script and beyond.

This understanding carries particular significance for the study of Osiris and related figures within the storm god archetype’s migratory mythos. Osiris’s association with the vine and wine is well-documented within Egyptian mythology, symbolizing death, rebirth, and the cyclical nature of life itself. Names such as Oswin, blending the divine “Os” with “win” (wine/vine), further underscore this symbiosis between god and grape. By tracing the “vin” root’s ancient agricultural and linguistic heritage, we uncover a tangible cultural continuity that connects early European viticulture with Egyptian religious symbolism, and ultimately with the storm god’s journey as it transforms and diffuses into Celtic Britain. This foundational layer, grounded in earth, water, and vine, illuminates the intertwined evolution of myth, language, and material culture that underpins the entire saga.

Far from being mere fanciful stories, myths can be seen as early human attempts to comprehend, control, and communicate the necessities of survival. The stories of flood and storm, of harvest and craft, of birth and death, are narratives born out of the human need to understand the environment and pass vital knowledge through generations. In this way, mythology is both a cultural memory and a survival manual, encoded in symbolic form.

And it is to myth that we shall now turn our focus. To identify our Storm God as a natural observable phenomenon that served to fulfil the need for psychological reassurance that water and fertility would continue and sustain the people, even when the seasons would change and scarcity would have been evident. It is the constant reminder to the people that there is a principle in the very architecture of Creation that assures a certainty that life will go on, and be supported by a father and mother through good times and bad. This is a natural need in human beings, whether ancient or modern.

So we see how logical it is to assume that science and myth developed hand in hand with technology, and eventually finer forms of mathematical and philosophical disciplines. As man would depend on his calculations to also know when to plant, when to harvest and when to store his harvest, and how to manage his livestock and maximize yield over expenditure of energy.

Further information

For more on the archaeology at the Vinca site of Belo Brdo - see: Archaeological Site Belo brdo in Vinča

For those intrigued by the spiritual and symbolic power of early writing systems, the essay “Sacred Script” by Cari Ferraro offers an illuminating perspective that first inspired me to take a deeper dive into this exploration of the Vinča culture:

https://cariferraro.com/library/essays/sacred-script/

Return of the Storm God Part 2

For over a century, the dominant academic model held that writing, ritual, and metallurgy spread north westward from Mesopotamia into Europe. Early sign systems in the Balkans were thus interpreted - if noticed at all - as provincial imitations or isolated symbolic detours. But this view is now collapsing under the weight of evidence.