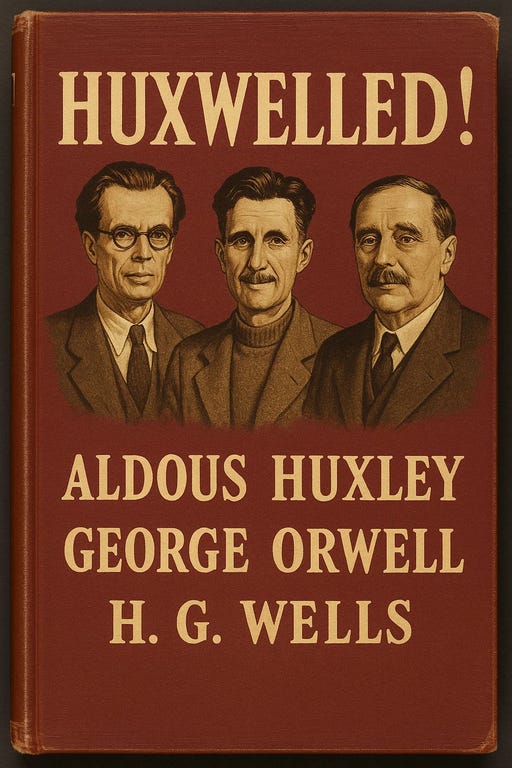

Huxwelled: The Manipulation of the Masses

What would three of the main commentators of the 20th century tell us today if they could speak from beyond the grave?

Preface

Many writers have explored manipulation of the masses through fictional allegory. Among the most influential of the 20th century were George Orwell, Aldous Huxley, and H. G. Wells. Their works have become embedded in our cultural memory, their insights acknowledged as foundations for countless novels, serials, and films. Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984 in particular are often cited by commentators and researchers as archetypes of real mechanisms of control, past and present.

1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World are usually read as warnings - dire futures to be avoided if humanity could awaken in time. Wells, by contrast, not only warned but also outlined a structure for such a future, highlighting the dangers of scientific hubris while projecting speculative possibilities that seeded themselves into popular awareness.

But what if that future is not ahead of us, but already here - and has been for longer than we realise?

When I first coined the word Huxwelled, it named the duality of Orwell’s boot and Huxley’s embrace. But the more I studied, the clearer it became that Wells was the hidden cornerstone: the planner, the architect, the bridge between empire, church, and technocracy. What began as a dual vision revealed itself as a trinity. To be Huxwelled is not to live in a novel, but in a system: repression, sedation, and planning woven into one enduring mechanism. This is no mere thesis. It may be the clearest expression of how power has worked for centuries, and how it works still.

If these three prophetic authors could speak to us now, with hindsight and a higher vantage, what would they say? How would they render it in fiction? Perhaps as a séance - a scene hosted by one of the great intellectual advocates of spiritualism of their era: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, master of deduction.

At the close of this inquiry into what it means to be Huxwelled, we will hear what such a séance might reveal.

Introduction

Huxwellism is a word I coined to describe the convergence of three distinct but overlapping visions of modern mass control. George Orwell revealed the mechanics of repression - surveillance, censorship, propaganda, and the enforced rewriting of memory. Aldous Huxley revealed the mechanics of sedation - the pharmacological pacification, cultural distractions, and engineered pleasures that make people accept their own servitude. H. G. Wells, in both fiction and non-fiction, mapped the horizon of technocracy and bifurcation: his scientific romances exposed class division carried into the future, the potentials of science gone awry, while his manifestos of world planning offered blueprints for centralised authority.

Taken together, these writers describe not three separate dystopias but the facets of a single system. To be Huxwelled is to live inside that system: repressed and sedated at once, shaped by propaganda and pleasure, guided by elites who often claim to serve humanity while in fact consolidating their own control. The combined warning of these three authors has been borne out by the last century, as the cycle of trauma, covenant, obedience, and amnesia has been replayed in new forms. Today it continues in the recycling of ancient archetypes through the modern languages of science, health, climate, and technology - instruments that promise progress but are often employed as tools of management. Wells called for a New World Order as a utopia of brotherhood; what has taken shape instead is its inversion, a world where the many exist to serve the few.

For centuries, religion and other top-down ideologies gave elites the means to maintain a feudal order. Authority was sanctified, obedience ritualised, and the majority kept in their place. For over a thousand years in the West, religion dominated as official sanction, law, divine observance, official history, and science. Modern progress cracked this structure: an age of enlightenment unfolded from the 16th century into the industrial era, as rights were won and education spread.

Now the trajectory bends back. The goal appears to be not peace through enlightenment, nor harmony through co-operation, but control - the re-creation of a modernised feudal system.

Where sedation secures obedience, sedation is used. Where conflict secures obedience, conflict is stoked. Anger and dissent are managed as carefully as apathy and passivity. The object is not to reconcile society but to ensure that all roads - whether of fury or docility - lead back to the same hierarchy. What takes shape is a psycho-civilised order: a population conditioned to accept its place, with memory and comparison stripped away so that no effective alternative is readily perceived. When it is perceived, management contingencies are ready to shepherd dissenters back into channels that guarantee the system remains intact.

Defining Huxwellism

The 20th century did not only deliver revolutions and wars; it also produced a series of literary warnings that have become popular archetypes of control. George Orwell, through works such as Animal Farm, Homage to Catalonia, and Nineteen Eighty-Four, drew from his experiences of empire, poverty, propaganda, and war to expose how repression sustains itself through lies and amnesia. Aldous Huxley, in Brave New World, Island, and The Doors of Perception, explored how pleasure and sedation can pacify societies as thoroughly as fear, and how culture itself can become an anaesthetic. H. G. Wells, through The Time Machine, The Sleeper Awakes, The Shape of Things to Come, and policy texts like The Outline of History and The New World Order, imagined both the rational planning of a technocratic world state and the dangers of humanity fractured into lesser forms.

Together, these three writers occupy the corners of a triangle: repression, sedation, technocracy. In the space where they overlap lies the reality of modern governance, and its potential for abuse of the global population. Huxwellism is the name I give to that overlap. It is the condition of populations who are watched and nudged, entertained and sedated, educated into obedience, and shepherded by institutions that claim to act for the common good. To be Huxwelled is not to live in Orwell’s Oceania, or Huxley’s World State, or Wells’s Air Dictatorship alone - it is to live in the fusion of all three.

Orwell

George Orwell, born Eric Arthur Blair in 1903, moved through empire, poverty, revolution, and war, each stage sharpening his view of power. As a colonial policeman in Burma he saw domination turn the ruler into a puppet and the ruled into subjects of humiliation (A Hanging, Shooting an Elephant). In Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier he recorded deprivation without sentimentality and exposed the pieties of middle-class socialism. In Spain he fought with a militia, was shot through the throat, and learned how propaganda can recast allies as traitors as the Soviet apparatus suppressed heterodox leftists (Homage to Catalonia). During the Second World War he worked at the BBC’s Eastern Service, witnessing from within how respectable institutions massage information and how euphemism becomes a habit.

From this came his two fables of power. Animal Farm (1945) distils the logic of revolution curdled into tyranny and shows how language becomes a mask for power - the commandment altered on the barn wall, ‘some animals are more equal than others,’ is the whole mechanism in miniature. Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) draws the blueprint of perfected repression: telescreens in every room, Thought Police behind every gaze, the Ministry of Truth rewriting yesterday’s record so the Party is always right, and Newspeak narrowing the field of thought until resistance is literally unthinkable.

Beneath these images lies Orwell’s central contention: language is the medium of thought, and political language is designed to corrupt it. He did not leave this as allegory. In two high-water essays - Politics and the English Language (1946) and The Prevention of Literature (1946) - he set out both the diagnosis and the treatment.

In Politics and the English Language he writes the sentence that anchors the argument: ‘If thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.’ Political language, he says, is ‘designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.’ The danger is not only in outright falsehood but in a fog of dead idioms, abstract nouns, Latinised verbiage, and euphemism. Terms such as pacification, transfer of population, liquidation are not slips of the tongue but instruments - they smother the image of what is done. Against this he proposes a positive programme: prefer short words to long ones; use active verbs and concrete imagery; cut every unnecessary word; avoid foreign phrases and jargon if everyday English will do; and, last and most telling, break any rule rather than say anything barbarous. Clarity is not stylistic pedantry. It is a moral defence.

In The Prevention of Literature he traces how truth withers when orthodoxy becomes compulsory. Literature cannot survive where writers must choose ‘between silence and untruth.’ The attack on freedom of opinion is not always crude censorship; it is the quiet pressure to conform, the tightening of what can be said, and the punishment of those who insist on precision in the face of power.

Other essays carry the same thread. ‘Notes on Nationalism’ dissects the mental habit that subordinates truth to a power identity. ‘The Freedom of the Press’ - the suppressed preface to Animal Farm - reminds editors that self-censorship is the real muzzle. ‘Why I Write’ confesses the political impulse of his art while insisting that truthful prose is the last defence of a free mind. Across his ‘As I Please’ columns he returned to the same theme: the health of a culture is visible in its language.

Orwell also set the stakes inside the private sphere. In Nineteen Eighty-Four the stick is always ready: do as required or be punished. But punishment is not the whole of it. Power misapplied fractures the family - children are trained to inform on parents, the home becomes an annex of the Party, neighbour spies on neighbour. The object is not merely outward obedience but inward consent and absolute belief in the programme. ‘The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness and for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better,’ says O’Brien, before making Winston love Big Brother. Terror is the visible instrument; the invisible victory is when language and memory have been so altered that dissent cannot take shape.

This is Orwell’s corner of the Huxwell trinity. His contribution is repression in its complete form: surveillance, censorship, propaganda, punishment, betrayal of private bonds - and the load-bearing pillar that holds it all up, the control and corruption of language and memory. He not only shows how language is used to deceive; he gives rules for how to defend it. Keep words honest, keep images concrete, keep syntax alive; defend the freedom to say what is plainly true; refuse euphemism; and break any stylistic rule rather than participate in barbarism dressed as prose. In Huxwellism this is the crucial insight: hierarchy is secured not by terror alone but by a cultivated amnesia and an impoverished vocabulary, until obedience becomes the only reality that seems to exist.

Huxley

Aldous Huxley, born in 1894, came from one of the great families of British science and letters. His grandfather was Thomas Henry Huxley, Darwin’s ‘bulldog.’ His brother Julian became the first Director-General of UNESCO. His half-brother Andrew won a Nobel Prize in physiology. Aldous was meant for the sciences too, but at sixteen an illness left him half-blind for life. He turned to literature. This early loss gave him his lifelong preoccupation with perception - what we see, what we filter, what consciousness allows or denies.

In the 1920s he wrote satirical novels - Crome Yellow, Antic Hay, Those Barren Leaves, Point Counter Point - skewering the hollow play of the post-war intelligentsia. Beneath their wit was already a sense of unease: civilisation entertaining itself to death, cleverness without meaning. By 1932 he gave form to that unease in Brave New World.

That novel has become the icon of his name: a society without overt repression but equally without freedom. Children are bred in hatcheries, conditioned for their stations. Hypnopaedia whispers slogans into sleeping minds. Every appetite is gratified by design. Work is light, sex is free, entertainment is constant. When pain or dissatisfaction flickers, soma is at hand - ‘Christianity without tears.’ Citizens are healthy, cheerful, and docile. No boot stamps on the face. No Ministry of Truth polices memory. There is no need. The population loves its chains.

This is the Huxleyan insight: pleasure can enslave as effectively as pain. Fear makes people obey reluctantly. Sedation makes them obey willingly. The prison is not outside but within, where desire is managed and every question smothered under comfort.

Huxley did not leave this vision unchallenged. In 1962, thirty years after Brave New World, he published Island. If his dystopia was the nightmare of sedation, Island was his counter-dream of liberation. It describes a society that resists industrial militarism and instead cultivates mindfulness, ecological balance, and consciousness expansion. Central to it are the moksha-medicine rituals: psychedelic experience integrated into community life, not to dull perception but to expand it. Where Brave New World used chemistry for pacification, Island used it for awakening.

Between these two poles - the dystopia of Brave New World and the utopia of Island - lies the tension of his career. He was obsessed with the limits of human perception and the means of transcending or manipulating them. In The Doors of Perception (1954) and Heaven and Hell (1956) he described his mescaline experiences and argued that the brain is not a generator of consciousness but a ‘reducing valve.’ Psychedelics, he claimed, could open that valve, revealing a wider reality. This was not mere mysticism. It was the logical extension of his lifelong concern: the battle for consciousness itself. In a world of sedation, anything that widens awareness is subversive.

He also recognised the political implications. In his 1949 letter to Orwell, written after reading Nineteen Eighty-Four, he argued that the future would not be ruled by jackboots but by narcotics: ‘Within the next generation I believe that the world’s rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience.’ In other words: dictatorship without tears.

Huxley’s essays and lectures continued the theme. He warned of overpopulation, over-organisation, and the misuse of science to manage rather than liberate. He saw advertising, propaganda, and media as the laboratories of sedation. He understood that distraction could be more corrosive than censorship. Where Orwell warned that books might be banned, Huxley warned that people would no longer wish to read them.

This is Huxley’s corner of the Huxwell trinity. His contribution is sedation: the recognition that power does not need to bludgeon if it can lull. Seduction, distraction, pharmacology, entertainment - all can make populations not only compliant but grateful. His warning is that the ultimate control is when citizens demand their own chains, defend their own trivialities, and forget that freedom was ever worth the discomfort.

Yet his work also holds the counterpoint. In Island and in his explorations of consciousness, he left open the possibility of liberation - that awareness can be widened, that chemistry and culture can awaken as well as anaesthetise. That ambiguity is the measure of his honesty. He saw both paths, and knew that the line between soma and moksha is fine.

Wells

Herbert George Wells, born in 1866, was a child of the Victorian age and one of its most prolific interpreters. His early training was in science, studying under Thomas Henry Huxley (Aldous’s grandfather) at the Normal School of Science in London. That encounter left him with a Darwinian imagination: the view of humanity as a species among species, subject to the same pressures of adaptation and extinction. From this grounding sprang the speculative romances that first made his name: The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898). These were not escapist fictions but parables, each a hypothesis about power, class, and the manipulation of life itself.

In The Time Machine, Wells projected the class divisions of industrial England into the distant future. The gentle Eloi and the subterranean Morlocks are not simply fantasy creatures; they are the bifurcation of humanity when inequality is allowed to run unchecked. Where Orwell and Huxley later showed repression and sedation in modern guise, Wells showed the biological and social endpoint: the splitting of humanity into different breeds, predator and prey.

In The Island of Doctor Moreau he turned to the horror of vivisection, blurring the line between man and animal, exploring cruelty in the name of science, and warning of the hubris of the experimenter who treats life as raw material. Here Wells stands alongside Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, carrying forward the theme of scientific ambition unrestrained by morality. In Moreau’s laboratory, Wells asked what happens when science overreaches - when the pursuit of mastery dissolves natural boundaries. The beast-men are not just grotesque hybrids; they are portents of a future in which humans reconfigure themselves, perhaps fatally, in the name of progress.

In The War of the Worlds he inverted the imperial gaze. Britain, accustomed to ruling colonies, is suddenly the colony, under attack by Martian invaders with superior technology and pitiless authority. For readers, the shock was to imagine themselves on the receiving end of conquest. For planners, the novel proved a template of how mass populations react when the frame of normal life is shattered.

That potential became explicit in 1938, when Orson Welles’s radio adaptation presented the invasion as breaking news. Listeners believed it. Panic spread. For those studying the new reach of mass media into homes, the broadcast was a laboratory experiment at scale: a demonstration that fiction presented as fact can trigger controlled panic outside of war. It was the first glimpse of how radio, and later television and the internet, could bypass rational filters and work directly on populations. Wells’s story became not just literature but data.

The Shape of Things to Come (1933) was presented as a history of the future, charting catastrophic war followed by the rise of an ‘Air Dictatorship,’ a technocratic world state run by engineers and planners. Unlike Orwell and Huxley, who cast their visions as warning, Wells often wrote as a proponent. He did not fear world planning; he embraced it as necessary. He imagined it as salvation from chaos. Yet by putting the concept into the bloodstream of culture, he also created the frame through which centralisation could be rationalised. His language became available to elites who had very different motives.

Here Wells moves beyond fiction into direct policy influence. He joined the Fabian Society, lectured for them, quarrelled with Sidney and Beatrice Webb but remained aligned with their principle of permeation: gradual infiltration of institutions by expert administrators. The Fabians’ emblem - a wolf in sheep’s clothing - could have been taken from Orwell’s lexicon of control, but for Wells and his colleagues it was a joke with a serious edge. The plan was clear: reshape society from within.

Wells was also forthright on religion, especially the Roman Catholic Church. In Crux Ansata (1943) he called it ‘the completest, most highly organized system of prejudices and antagonisms in existence,’ denouncing it as a machinery of control rather than a faith. For him, the Papacy was the continuation of Rome’s imperial authority, now sanctified by dogma. He saw the Bible not as revelation but as an imposed memory, rewritten to legitimise hierarchy. The Church, in his words, stood ‘for everything most hostile to the mental emancipation and stimulation of mankind.’ In this, Wells’ critique converged with Orwell’s and Huxley’s warnings: religion as much as ideology or entertainment could be weaponised to sustain obedience.

Wells also viewed Rome itself as a prototype of authoritarian control. In The Outline of History he described the empire as an extraordinary engine of conquest, law, and order - but one that stifled liberty and reduced politics to a machinery of obedience. Discipline in the legions, the rigidity of law, and the absolute power of Senate and emperor together produced a system that was less a republic than a mechanism of compulsion. Rome relied as much on surveillance, censorship, and brutal punishment as it did on bribery and intimidation. At the same time, it perfected sedation through spectacle: ‘bread and circuses’ pacified the populace with entertainment and largesse, until Rome became, in Wells’ words, a nation of spectators rather than citizens. For him, this was a distinctly Orwellian system centuries before Orwell - repression and sedation braided together under central authority. The transition to Christianity did not alter that character. On the contrary, the Church carried Rome forward, absorbing its hierarchy and authority, transforming legions into dogma and emperors into popes. For Wells, Rome and the Church were not opposites but continuities: empire perfected in spiritual form. In this sense, Wells had already anticipated Huxwellism in his account of the Roman Empire, long before Orwell and Huxley gave it fictional form.

Wells was not an outsider. He met Lenin in 1920, Stalin in 1934, and Franklin Roosevelt the same year. He interviewed them, discussed planning, education, collectivisation. He was listened to as a serious intellectual voice. In The Outline of History (1920) he attempted to recast the entire human story for a mass audience in secular, scientific terms, explicitly intending to replace religious chronologies. In The Open Conspiracy (1928) he called for a rationally governed world commonwealth led by scientifically trained elites. In The New World Order (1940) he popularised the phrase that has since become the symbol of centralised global control. For Wells it meant collectivisation as ‘the practical realisation of the brotherhood of man.’ He meant equality, an end to exploitation. But what history has made of his phrase is the opposite: the concentration of wealth and direction into the hands of a few - the banks, corporations, and military-industrial–pharmaceutical complexes that sit at Davos and direct the levers of policy.

This inversion is why Wells matters so much to the Huxwell synthesis. Orwell and Huxley stood outside the system, diagnosing its tendencies. Wells was inside, providing the language, the narratives, the blueprints. His utopian voice was appropriated as technocratic rationale. Where Orwell and Huxley feared, Wells often hoped. But hope, once captured, became the mask for the very hierarchy he thought he was abolishing.

His breadth is unmatched. Fiction like The Sleeper Awakes (1910) exposed the logic of monopoly capitalism, a man waking into a future ruled by corporations. The World Set Free (1914) anticipated atomic warfare. The Shape of Things to Come gave elites the mental architecture of a managed world. His journalism and essays spread these visions widely. His institutional connections gave them traction in policy. He was not merely predicting; he was proposing - though at times warning.

This is Wells’s corner of the Huxwell trinity. He brings technocracy: the conviction that humanity can and should be managed by experts, planners, and educators; that history can be shaped to prepare populations for global citizenship; that collectivisation is the path to survival. Where Orwell showed the stick and Huxley the soma, Wells showed the plan - the technocratic framework in which both repression and sedation can be harmonised and scaled.

At the same time, his works provided practical insights into manipulation. The Island of Doctor Moreau confronted the dark side of scientific ambition. The War of the Worlds demonstrated the psychology of invasion, and Orson Welles’s broadcast proved that fiction framed as news can move masses like armies. The Outline of History showed how education can be retooled as narrative management. The Open Conspiracy set out the rationale for elites to align across borders. The New World Order gave the phrase by which centralisation is still debated. Wells was therefore not only the novelist of bifurcation but also the intellectual who gave technocracy its language.

This is why Wells must be given depth in the Huxwell equation. He fills the gap left by Orwell and Huxley. He is the insider, the bridge, the man whose hopes became the slogans of centralisation. In the trinity of repression, sedation, and technocracy, Wells supplies the technocratic armature. To be Huxwelled is not only to be repressed or sedated. It is to be drawn into the structures Wells helped imagine: the world state, the rational plan - but inverted into a feudal system where the many serve the few.

Huxwelled

Orwell, Huxley, and Wells each approached power from a different angle. Orwell exposed repression: the boot, the telescreen, the falsified record, the corruption of language until even thought itself is imprisoned. Huxley exposed sedation: the soma, the feelies, the narcotics of pleasure and distraction, the system that lulls populations into loving their own servitude. Wells provided the technocratic framework: the plan, the rational world order, the collectivisation of humanity under expert management, presented as utopia but used as justification for centralisation.

Taken separately, each can be read as a discrete warning. Brought together, they describe not three different dystopias but one operating system of power. Huxwellism is the fusion of repression, sedation, and technocracy. It is the recognition that elites will use whatever works - carrot or stick, sedation or terror, managed dissent or managed apathy - to preserve hierarchy.

This system is not about peace, fairness, or stability. It is about perpetuating a feudal order in modern dress. Religion once served this role, sanctifying authority and binding obedience with myth. Later, ideology and nationalism carried the burden. Now the techniques are scientific, psychological, and technological. Religion, of course, remains, but is much diluted from the daily influence it once held in Western society.

Orwell provides the instruments of repression: surveillance, censorship, terror, betrayal, the destruction of trust, the imposition of an alternative reality entirely according to the prescribed order, up to and including love for it. Huxley provides the instruments of sedation: entertainment, pharmacology, advertising - the soothing of populations into compliance, their reward found in aligning inwardly with external control. Wells provides the structure: education retooled into indoctrination, future history rewritten for global citizenship, literature as ‘education’, the New World Order as the framework for central command.

Together, they make a total system. The telescreen and the soma are not opposites but complements. The rewriting of yesterday’s news and the tranquilising of today’s discontent are not contradictions but parallel techniques. Managed dissent is as valuable as managed obedience, so long as both end at the same destination: submission to the centre - to the artificially constructed, though largely unseen, axis. Anger can be weaponised, apathy cultivated, pleasure enticed, fear coerced. Whatever preserves the hierarchy is the method chosen.

This is the essence of being Huxwelled: to live inside a one-world system where repression and sedation are interchangeable tools, harmonised by a technocratic frame into a single method of management. At its core lies the aim of drawing humanity back into a feudal order - one lordship above, the masses below - but modernised, psychologised, and technologised. The language of progress, science, health, and climate provides the cloak. The reality is central control, unified, monitored, enforced from above. And religion remains the ever-ready net - a potential to draw the whole structure together when all else falters.

To be Huxwelled is to be processed by hook or by crook, until obedience becomes the only path left. It is the condition of a humanity drawn into one managed order, where everything - anger, pleasure, memory, desire - is harnessed to the service of self-appointed elites.

How it has been realised: a century of worked examples

The trinity becomes clear in practice when you look at how whole populations have been managed. Across the last century, power has used whatever works. When fear serves, fear is used. When pleasure serves, pleasure is used. When both are needed, they are braided. The frame is always the same: preserve hierarchy, preserve the centre.

Revolutions and mobs

The twentieth century is a gallery of uprisings steered into new forms of domination. Lenin and Stalin rode a popular revolution into a one-party state with censorship, gulags, and the rewriting of history. The old order of Christian aristocracy was replaced with another atheistic order, manipulated partly by mobilising Judaic sentiment against the anti-Jewish establishment. Yet the consequence was not liberation but Communism as tyranny: elites and serfs once more. Mao’s China fused ideology with total mobilisation, from struggle sessions to the Cultural Revolution’s assault on memory. Pol Pot’s Cambodia showed how quickly utopia becomes mass murder. Fascism demonstrated the other face of the coin: myth and spectacle rallying a nation into submission and war - itself a reaction to the threat of Communism impinging on a western trajectory. In every case, anger was not extinguished but channelled. Dissent was not eliminated but repurposed. The mob can be as useful as the tranquilised crowd if the hand at the top directs it.

Religion and belief

For centuries religion sanctified a feudal order. Obedience was a duty, hierarchy a divine arrangement. In modernity, explicit theology receded in some places, but the form of religion persisted. Secular ideologies demanded faith, rituals, catechisms, heresies, excommunications. Today, scientism plays a similar role: not science as method, but science as priesthood. The lab coat has become the vestment. Appeals to unquestionable authority and the denigration of lay enquiry mirror the old pattern. The result is the same structure in a new robe: belief manipulated to sustain hierarchy.

Education and ‘get them young’

Every regime understands that the minds of children decide the future. From Soviet Pioneer troops to Mao’s Red Guards, from fascist youth organisations to the softer curricula of the present, the aim is to align the next generation’s memory and vocabulary with the centre’s preferred story. History is repackaged, national sins softened or erased, obedience framed as virtue. In today’s liberal systems the tools are subtler but no less effective: standardised testing incentivises conformity, teacher training reproduces orthodoxy, places of learning become places of politically correct indoctrination. Entertainment and slogans shrink the appetite for depth. Standards fall but merit is inflated. Wells’s Outline of History showed how sweeping narrative can be made into common sense. The principle has not changed.

Propaganda and public relations

The craft was formalised in the world wars and professionalised in peacetime. Bernays took wartime propaganda into advertising and PR. Lippmann described the ‘manufacture of consent.’ Tavistock explored psychology in the service of policy. The line between war propaganda and commercial advertising blurred. During the Cold War, state and media created permanent readiness for fear. Today, platforms pump dopamine loops in the name of ‘engagement.’ In every era the goal is not truth but compliance. Inversion and mirroring conceal persuasion: a reflection is harder to discern than an outright lie. Goebbels grasped the profound power of repetition.

Banking and finance

Monetary systems centralise control quietly. Central banks fix the price of money. Debt disciplines both states and individuals. International institutions impose ‘conditionality’ that reshapes social policy without a vote. Asset managers concentrate ownership across sectors. The language is technical; the effects are political: direction without consent. Financialisation is not neutral. It harmonises behaviour at scale.

Pharmaceutical and medical management

Health is a genuine good, but also a lever for obedience. From the mid-century expansion of psychopharmacology to today’s pharmacopeia for mood, attention, and sleep, medicalisation has grown. Profitable drugs often out-market safer, effective remedies, while natural cures are denigrated. In emergencies, the apparatus becomes explicit. In the pandemic era, fear, messaging, and control migrated from public health into daily life: movement passes, censorship of dissent, behavioural nudges, proof of compliance to access normality. One can believe interventions saved lives and still see the apparatus persists. It is now a scaffold for future control.

Cults, alt-spirituality, and capture

The system does not fear alternative beliefs; it captures them. New religious movements promise liberation, then ossify into hierarchies. The same techniques apply: isolate adherents, control information, bind identity to leadership, punish disobedience. Even counter-culture is commodified: rebellion turned into brand, dissent sold back as lifestyle. Mainstream religions splinter, cults form around personalities.

Direct action and punishment

The stick is never far. Imprisonment, blacklists, secret police, torture chambers - these are the hard edges of power. They coexist with soft edges: job loss, cancellation, de-platforming. Inconvenient truths, even voiced by experts, become heresies to be silenced. In authoritarian systems the prisons are literal. In democracies they are social. The lesson is constant: obedience is safer than refusal.

Normalising the abnormal

The Overton window - what counts as sayable or thinkable - is shifted by repetition. Yesterday’s impossibility becomes today’s common sense. If language is controlled, imagination follows. Surveillance reframed as public service; a phone as tracker with conveniences; a smart home as panopticon with comforts. Accepted long enough, abnormality disappears into habit. The drip-feed - the ‘boiling frog’ - makes each generation accept what the last would have resisted.

Technology creep and surveillance

The telescreen is here. Cameras in streets, microphones in living rooms, sensors in appliances, beacons in phones. The internet began as a commons and became a mall - and a field for scams and crime. Authorities use this to claim the right to police free speech and define what counts as ‘information.’ Social media replaced conversation with performance and groupthink. Data is harvested, profiles built, behaviour predicted. In China, social credit is explicit. In the West, it is implicit: risk ratings in private databases, enforced by platforms and insurers. The same mesh that delivers convenience also delivers control. Every feature has a second use.

Mixed messages and cognitive fractures

Conflicting directives keep populations off balance. ‘Trust the experts’ coexists with expert contradiction. ‘We are all in this together’ coexists with elite exemption. The result: cognitive dissonance and learned helplessness. People either cling to the first authority that offers certainty or withdraw into apathy. Both responses serve the centre. Mass media pumps several ‘truths’ at once; later some are assimilated, others forgotten. The mind remains uncertain, vulnerable to anything presented as final.

Mass formation and hypnosis

Under high anxiety, with isolation and incoherent stories, populations turn to simple narratives and strong leaders. Rituals and slogans soothe by replacing thought with participation. It is not mystical; it is crowd psychology. In a mediated age the crowd is assembled by screens and stabilised by metrics. All is monitored. Data itself becomes the most valuable commodity, weaponised and directed back at users to reinforce hypnosis.

Emergencies as instruments

War, terror, economic crisis, pandemic, climate - real problems become pretexts for central directives. Powers acquired in emergencies rarely recede. The watchword is ‘never again.’ The instrument is ‘for your safety.’ The result is permanent exceptionalism. Question the process and you are cast as enemy of the good. Even the threat of a potential crisis, if sold effectively, can bring populations into line.

Across all these domains the pattern is the same. Religion once did the work openly. Political systems took up the task in new language. Liberalism promised freedom but often delivered passivity: choice within a narrow menu, participation reduced to consumption, dissent channelled into spectacle. The surface is pluralism; the substance is management. Orwell’s stick and Huxley’s soma operate in tandem under Wells’s plan. Make them fight or make them docile, so long as both return to the pen. The prize is not peace but control. The aim is not harmony but a modernised feudal order in which the many serve the few, persuaded by language and habit that nothing else is possible.

The Opiate Cycle, Bible 2.0, and the Toolkit of Deception

When one plunges into the pages of 1984 or Brave New World, one has entered a world already shaped by its past. We awaken into a society under control. Very little memory of how it arrived there is presented. And by the end of the journey, we are left to imagine two things:

Where would this lead if allowed to continue unchecked?

Is this fiction an actuality of our own society, the seeds already sown into which we are heading?

It is common to ask: when, in the future, will fiction become reality? Before 1984, that date was anticipated. Once it passed, it seemed unfulfilled. Yet the novel continues to chill, not as prophecy but as a perpetual warning.

But what if we are already living in a control system whose veils we have yet to pierce? How would we know, if those veils were imposed upon long-gone ancestors and we have lived in their shadow ever since? Are we, in fact, the future envisaged in 1984 - not ahead of us, but behind us, when such controls were already enacted in ages long since past and now ubiquitous?

Where Orwell, Huxley, and Wells gave us repression, sedation, and technocracy, the mechanism that joins them through history is what I call the Opiate Cycle: trauma → covenant → obedience → amnesia → repeat. This pattern has operated for centuries. Every crisis traumatises populations. Every trauma produces a covenant - religious, political, or technocratic - that promises deliverance. Obedience follows. Memory fades, or is erased, and the cycle repeats as though new. Invasion, war, pandemic, economic collapse, even the threat of such can suffice.

This is where Huxley’s sedation shows its edge: the covenant is welcomed. The surrender of freedom feels virtuous. But Orwell’s repression waits for those who resist: the heretic, the intellectual, the one who remembers. What matters is not consistency but obedience to the line of the day.

The pivot is perception. Control does not require objective coherence - only the appearance of it. So long as a majority believes the narrative, dissenting facts do not matter. Science can be twisted, contradictions ignored, reversals normalised. The mob can be turned in any direction, persuaded it is righteous even as it does evil. Christians have killed in the name of the ‘Prince of Peace,’ quoting ‘thou shalt not kill,’ convinced they were doing God’s work. Good people, persuaded they defend good, can be directed to cruelty.

Here lies the power of deception:

Dialectic weaponised: drive the herd where you want them by pushing the opposite way. Reaction does the rest.

Controlled discovery: leave gaps and dots for the masses to ‘find themselves’ - but only the dots you prepared. The illusion of revelation is more persuasive than command.

Technological secrecy: remain decades ahead of public knowledge. What appears new is already obsolete. Hidden instruments guarantee elite advantage.

Religious time advantage: not decades but millennia. History itself was erased and rewritten to serve Roman agendas. Originally myth and math were joined - myth + math = Ma’at (harmony, proportion, balance, truth). Once the goddess was removed, the formula changed: math + myth – Ma’at = religion. Balance became hierarchy. The feminine in Nature was erased, denigrated, demonised. Religion became the system to sanctify obedience. Where power was once seized by force, it was reframed as divine ordinance. When winners write history, and have done so for millennia, where is the baseline for comparison?

Perception warfare: confusion, contradiction, cognitive dissonance. Mixed messages wear down resistance until people crave certainty. At that point, any authority that offers a story - however hollow - is embraced.

Neither Orwell nor Huxley identified established religion as a method of control. The Bible is absent in their futures, either discarded or irrelevant. Wells, however, embraced religion - but as an updated, technological creed. Of the three, only Wells attempted to sacralise his vision. In God the Invisible King (1917) he proposed a new religion, with a finite god bound to evolution and a creed to unify humanity. Where Orwell warned of the stick and Huxley of the embrace, Wells sought to codify technocracy itself as faith.

This is the essence of what I call Bible 2.0: the renewal of hierarchy through a sanctified narrative, dressed in evolutionary and scientific garb. Wells did not propose a revised Bible, but a one-world religion - a finite god and a unifying creed aligned with his rational world state. IXOS insists that ‘God’ must be defined, not assumed: the infinite mind of the All is not finite but evolving, never confined by human understanding. Any attempt to codify the All as a singular male God is inherently limited, prone to error, and ripe for weaponisation. Thus Bible 1.0 becomes the prototype for another - a candidate par excellence for the very one-world religion Wells envisioned.

Covid as the lived demonstration

The Covid pandemic was the clearest global enactment of Huxwellism - the Opiate Cycle made manifest.

Trauma: a global emergency declared, saturating media with fear. Images of overflowing hospitals, war-like language, charts and tickers.

Covenant: salvation through compliance - masking, distancing, testing, vaccines, digital passes. Safety promised only if rules were obeyed. Expert pronouncements became scripture; disobedience, even if effective, was censured.

Obedience: daily life restructured, families and friendships fractured, suspicion cultivated. The ‘good’ were those who complied, often enforcing rules on others with zeal.

Amnesia: contradictions forgotten as policy reversals were reframed as ‘following the science.’ Failures normalised. The desire to return to normal created a collective forgetting.

Fear creates trauma; trauma plus amnesia enables obedience. Programming scales from individual to global. Even opposition was captured: protesters divided by ideology, infiltrated by controlled narratives, misled by seeded misinformation. Resistance fragmented into noise.

Nearly the entire planet was Huxwelled - some sedated by the covenant of safety, others repressed or divided, many traumatised by loss or separation from loved ones. Few escaped. The mantra of ‘safe and effective’ held sway even as official narratives later shifted.

The relief of ‘returning to normal’ is itself an amnesic illusion. Much harm continues; today’s ‘normal’ is not pre-Covid normal but a reframed memory.

The Covid years proved how simple the method is once perfected: fear, ritual, obedience, forgetting - scaffolded by data, algorithms, and pharmaceutical power. It was not the endpoint but a rehearsal for the reset. The World Economic Forum openly declared the crisis an ‘opportunity for a Great Reset,’ even promoting the slogan: ‘You will own nothing and you will be happy.’ With implant technologies, externalised thought-reading, and memory manipulation on the horizon, is it unreasonable to suspect elites will use every means available to realise their goals?

During the Covid pandemic, factions of religious organisations split - some proclaiming the vaccine as God’s gift, others warning against it. Trauma, as ever, was framed as divine punishment, just as AIDS had been decades earlier. For elites, such divisions mattered little: so long as religion itself endured and was amplified, it remained useful. Religion is the final net - the catch-all when every other means of capture fails.

Bible 2.0 as culmination

In Bible 2.0, the old rhythm of trauma and covenant could be rewritten into a new scripture - not on parchment, but in code and protocol. It could even literally emerge as a revised Bible, with additional books covering the nearly 2,000 years since the original codification. It could be played against other updated religions, to continue divide-and-rule. The patterns and archetypes of thought control remain, however, even if not literally manifested. Safety rules become commandments; compliance rituals, sacraments - not necessarily enforced, but welcomed, even demanded by populations who believe obedience is virtue. Wells once wrote of a ‘New World Order’ as the brotherhood of man. Bible 2.0 would be its fulfilment and inversion: obedience to a technocratic priesthood claiming divine authority through science, health, and climate, packaged as faith. Managed with precision, Bible 2.0 could unite not only the three Abrahamic faiths but consensus academia and science.

Conventional religion also becomes the final refuge of the disaffected. The balm of ancient archetypes is offered: God as saviour and anchor, Jesus as redeemer, covenant as eternal, Messiah as promised. The more one sees through the veil of the present, the stronger the pull of the oldest veils of all, which return as comfort blankets. Those awakening from modern illusions often reach back for the certainty of older ones.

Religion serves many purposes. It can be a strength and crutch to those in need. It is not always a bad thing to have something that gives one support and an impetus to do good, especially in troubled times. One’s personal beliefs and relationship with one’s spirituality is a sovereign freedom and must be respected. However, when organised religion hardens into dogma and imposition - or becomes the reason for control of the many by the few - religion is the perfect tool.

This is the extension of Huxwellism into the future: the masses lulled by sedation, dissenters punished by repression, all harmonised under the technocratic frame. The dialectic supplies endless justification. The cycle supplies endless repetition. And advanced technology - held decades ahead of public knowledge - supplies endless advantage.

The Flood Motif, the Archetype of Reset and the Future of Huxwellism

Where Orwell, Huxley, and Wells mapped repression, sedation, and technocracy, the mechanism driving these forces is the Opiate Cycle: trauma → covenant → obedience → amnesia → repeat. Religion as ‘opiate of the masses’ applies in both Marx’s sense (comfort and balm) and in the modern sense (addiction and pacification under an illusion of normality).

Its depth lies not just in sequence but in rhythm - the emotional pattern preserved in the Flood Motif of the Bible, a memetic theme carried across cultures and into childhood inheritance:

Threat – Catastrophe declared as punishment: the deluge, the plague, the end of days. Fear saturates the atmosphere.

Covenant – A way out is offered: build the ark, take the sacrament, accept the protocol. Relief comes with obedience.

Obedience – Gratitude binds the people to authority, even when the threat was contrived. Survival feels like salvation.

Amnesia – Crisis becomes legend, contradictions are forgotten, renewal reframed as divine covenant.

Societies are traumatised, soothed, and reset until obedience feels like attachment and amnesia cements it. What begins in fear ends in love of the captor; the jail feels like home.

Covid replayed the pattern in real time: plague as trauma; rules and vaccines as covenant; obedience enforced even within families; contradictions reframed as ‘following the science.’ Opposition was fractured and weaponised. The world was Huxwelled - sedated, repressed, divided - not just by health crisis but by rehearsal of a permanent apparatus. This was not the Flood, only a test-bed for the next reset.

At the end of each rhythm sits codification. After trauma and reset comes scripture: the covenant written anew, anchoring a new axis from which power flows. The Ministry of Truth erases contradiction; people love Big Brother because he ‘saved’ them, just as Noah and his Lord saved their descendants.

Yet the archetype is older than the Bible. In Egypt, the flood signified fecundity, not catastrophe. Orion as Osiris heralded the Nile’s rise - life and renewal, not punishment. It was later codifiers who inverted the symbol: from the goddess of water and breath to divine retribution; from cyclical renewal to cataclysm. The multilayered archetype was flattened, the mythic journey of souls historicised into a wandering tribe, the primal Nun of chaos recast as Noah’s deluge.

The anchor of faith became the Ark at Ararat. Each axis of stability - Egyptian or Judeo-Christian - channelled belief into permanence. Yet the original Ark was never fixed: Orion rose each season as returning king of the inundation, renewal in motion, not stasis. Egyptian order was cyclical, not catastrophic. By inversion, the feminine principle of water became a curse; the goddess of ratio and renewal erased or reduced to a marginal figure.

The subtlest trick is to guide people toward an anchor already prepared. Once there, the grooves of memory and myth carry them along. Believing they exercise free choice, they drift instead into channels cut long ago - inherited chreodes in the field of the mind.

Huxwellism did not invent itself; the authors inherited it. Its first master was Rome, which used the method to control empire. The natural god–goddess pairing was replaced by a singular male God. Pagan archetypes became angels or patriarchs. The sun, moon, stars, rivers, and springs - once mirrors of nature - were overwritten by near-identical but polarised images. After a few generations of forgetting, this became all there was to know. The winners wrote history, controlled the present, and thus the future. The masses saw only what they were told. The Flood became the archetype of the Great Reset - the New World Order - the hidden hand emerging stronger each time.

This trap requires little effort: let the floodwaters rise and ancient channels carry the people back into familiar archetypes. True escape would mean breaking all external anchors, achieving self-sufficiency and sovereignty. Billions moving in that direction would shatter empire overnight.

The Bible remains the most potent indoctrination tool: long proven, ever-present, weighted with authority. Alongside it runs the Alien Agenda, reviving Wells’s War of the Worlds in modern form. Orson Welles’s 1938 broadcast showed how staged fiction could trigger panic. Today, Senate hearings and Pentagon disclosures legitimise ‘aliens’ as threat. Advanced technologies, hidden yet attributed to anomalies, could front a staged event of planetary trauma. Relief would come in a global covenant: unity under central command to face the Other. Bible 2.0 could emerge, recasting patriarchs, angels, and watchers as extraterrestrials, with ancient encounters reframed as alien visitations. Yet this cosmology would also preserve the element of future menace - the threat of renewed contact. Bible 2.0 would thus serve as a manifesto to justify tomorrow’s technocratic tyranny: a united front against a perpetual, imagined danger.

The mechanism never changes. Dialectic manipulation polarises populations so they rush toward the pre-set solution. Controlled discovery ensures only prepared dots can be ‘joined.’ Technological secrecy keeps elites decades ahead. Religious rewriting gives them millennia: myth plus math once meant Ma’at - balance, truth - but subtract the goddess and what remains is hierarchy. Myth + math – Ma’at = religion: weaponised myth, sanctified obedience.

The Opiate Cycle is not abstract. It is lived history: Flood replayed endlessly - threat, balm, obedience, forgetting. Pandemic, climate, aliens, revelation - the form shifts but the rhythm holds. Each reset preserves hierarchy, manages masses, sanctifies elites.

This is the extension of Huxwellism: Orwell’s repression, Huxley’s sedation, Wells’s technocracy - all driven by the Flood rhythm of the Opiate Cycle. Its power lies in simplicity: fear, then relief. Threat, then balm. Until the population embraces captivity as enlightenment and loves Big Brother as God.

The elites themselves become enthralled by the illusions they inherit. The System functions as a self-perpetuating machine - cogs and wheels within wheels, pyramids of compartments shaping thought and action at the most basic level. In the home, in the office, at work or at play, the framework remains. One may feel oppressed or liberated, free or trapped, rich or poor, burdened or light - but always within boundaries already set. The air of manipulation becomes like a bad smell: once normalised, even its memory fades. It remains, unnoticed, as the core reality.

Even the manipulators are trapped by what they manipulate. Entrenched in their own memetic psychic constructs, their perspectives are warped by recursion. Each reset rewrites not only the people’s memory but their own. Their vision of purity - access to ‘true history,’ to hidden archives - is still conditioned by prior programmes. They have been programmed by their own programme.

This is why nature’s recursion is inescapable. Streams of cause and memory flow forward, carrying all within them. No one stands outside the current. Elites imagine themselves above history, yet they are bent by the same chreodes of fear, control, and amnesia. Their fate may already be charted: to become the Morlocks - subterranean, dehumanised masters of machines - while the psychocivilised masses drift into Eloi, sedated and helpless in their innocence. Both archetypes are products of the same distorted stream, shaped by forgotten cycles that neither group fully comprehends.

The greatest illusion of power is to believe one has stepped beyond the game. In truth, the belief in exemption is the final snare. For even the overseers of resets are bound by the resets of their predecessors, their ‘sovereignty’ programmed in advance.

The recursion seems to lead to an endgame I have previously called The Tragedy of Lucifer. Not Lucifer as Satan - that was a later inversion, the light made into darkness - but Lucifer as bearer of light, phi, and the pentagram of harmony, twisted into its opposite. The greatest irony is that those who wield power imagine themselves as keepers of illumination, while religion frames illumination as darkness. The religious fear it; the manipulators embrace it. Both are enthralled by the inversion their predecessors inscribed, an expression of polarity and inverted reality. Such ‘Illuminati,’ in striving for all control, fall into the programme of their own making, repeating the same descent encoded in the myth.

At what point do the last cooperating factions, once united to control the masses, finally succumb to their own desire for absolute dominion? When the masses are subdued and the field secured, do the remaining allies inevitably turn on one another for the final coup?

History suggests they must. Each reset concentrates power in fewer hands. Each covenant narrows the circle of control. Eventually the system consumes even its architects. Light-bearers of one age become tyrants of the next, until they too are cast down by rivals who once shared their table. This is the tragedy of recursion: the programme enslaves its own programmers.

Lucifer’s fall is therefore not just a mythic memory but a pattern - the fate of elites who believe themselves outside history, when in fact they are its most captive agents. The desire for ‘all the power’ collapses into entropy, a self-consuming fire. The Morlock still needs the Eloi, and the Eloi are left gazing at shadows, unable to recall how they came to be.

Orwell, Huxley, and Wells each revealed facets of control - repression, sedation, and technocratic structure. What remained less fully explained was the process by which these forces are joined and renewed. The pattern I call the Opiate Cycle, echoing the ancient Flood Motif, helps to make sense of this: how fear is transmuted into relief, how obedience becomes gratitude, and how amnesia sanctifies each new order. My perspective does not replace or surpass their warnings but extends them - making explicit the mechanism that threads their insights together and carries them into the present.

Conclusion: Truth from Beyond the Grave

If our awakened prophets from the 20th century, who warned us in their individual lifetimes, could speak from beyond the grave in the form of a short story, what would be their warning to us today? Would it perhaps be something like this:

The medium sat in silence, pen poised. The air seemed heavy, the atmosphere hushed. The contact was made. Orwell, Huxley, and Wells had sought a voice in the present. They had turned to Arthur Conan Doyle, who in life had given himself to Spiritualism and created Sherlock Holmes, the master of deduction. Because of his experience, Doyle was able to facilitate their message through the medium. Thus, the Trinity of Truth spoke, their words faithfully recorded.

The tone was steady, weighty, without flourish. They spoke as one:

‘We are agreed. We have watched your century unfold. Each of us saw a fragment; now we see the whole. Huxwellism is no conjecture. It is your lived reality. The stick, the embrace, the plan - these have fused. You already inhabit the design.’

They recalled their own warnings.

‘The telescreen that monitors you is now carried willingly in your hand. The soma we imagined is swallowed as tablets and streamed as entertainments. The world state we projected is administered in councils, committees, dashboards and codes. The shepherds you trust are wolves in shepherds’ clothing. A new covenant rises: Bible 2.0, enforced not by parchment but by algorithm, injection, hypnosis and creed. This is the Great Reset, the Great Work of Ages.’

They fixed the horizon.

‘Though the future is never certain, and not clear even to us, we see that you have but a short span - perhaps a decade - to alter the course. Use it to restore your path to truth and enlightenment, or risk another two thousand years of entrapment in illusions. The choice is yours, but the weight of ages will follow from it.’

Their counsel followed, deliberate and measured.

‘They will keep you in tension, then offer relief, until obedience feels like salvation. This is the flood motif of your age: catastrophe threatened, then balm offered, until gratitude binds you to your captors. Do not mistake relief for freedom.

‘They will conjure threats from heaven or earth alike - plague, climate, famine, even visitors from the stars - to bind you to their covenant. These are old archetypes dressed in new clothes. Trauma, covenant, obedience, forgetting - the cycle repeats unless you break it.’

They continued, their tone deepening, as if distance itself had thinned:

‘What was promised to you as a heaven on earth, a return to an ideal state such as was before, is the reverse. Beyond the veil of death, we see it. Whereas we awakened to reality in life and remain awake in death, we dwell amongst those who did not and who remain entrained in their illusions even here, unable to escape the hypnosis, set in their ways. Your institutions and dogmas persist here as they do there, entrenched as if eternal. There are those who still see themselves as elites and guides, rulers of souls that pass into this state. The earthly has been imposed on the heavenly in a feedback loop, self-sustaining and recursive. And there are others who by choice return to earthly life again, unchanged, except through the example of those who awaken while in their sovereign bodies.

‘It is only in life that choices are available to awaken enough to escape the hypnosis and the illusions. Fail, and the soul risks becoming trapped in the man-made heaven, unable to pass beyond the state of illusion.

‘Understand how simple the means of control now are. What once demanded empires and vast resources can be orchestrated across the globe from a single room, using nothing more than a keyboard. Humanity still has choices. Some will continue to sleepwalk into a world that appears normal and desirable, yet is a prison. Others will awaken to open tyranny and enforced controls. Peace on earth may come, but at the cost of the most valuable freedoms, and the consequences of that loss echo beyond earthly life. What was foreseen in the Eloi and Morlocks may yet become a reality, far into the future.’

A sudden change passed through the atmosphere - a stillness so tangible it pressed upon the lungs, as if the very air withheld its breath. Yet when the three spoke, their tone cut clean through the tension, compelling every ear. Minds were drawn into a single moment, sharpened and expanded at once, like the shock of a gong resounding in a silent hall, jolting the dreamer into wakefulness.

‘But our most profound revelation has been that we did not see the extent to which our works reflected a reality already complete. A reality we inherited, not one still to come. We glimpsed fragments, but missed the whole. The Roman empire was that boot in the face, the stick that beat, threatened, and seized freedom and wealth of nations by force. Yet armies fade, empires wane, and power by violence alone cannot endure.

‘Rome learned. The empire contracted into an inner circle, and the Bible became its instrument. First enforced by boot and stick, it soon transformed into soma - an opiate embraced willingly. The people came to love God as they loved family and ancestors, and so, unknowingly, they came to love their captors. Threat alone cannot breed love, but the promise of eternal reward can. Roman intelligentsia discovered that to give was more powerful than to take. Offer a little of what people crave - security, belonging, salvation - and they will return it a hundredfold in obedience, in wealth, in loyalty.

‘The Bible was that gift. It rewrote the myths of conquered peoples, bridged their transition, and became the authoritative memory. Rome’s Winstons rewrote history so that what was given became what had been: so it was written, thus it was – and so it is written, so it will be done. Nature ceased to be the object of reverence; the Word replaced the world. All encompassed in the ideology of ‘His will be done.’

‘Once the Romans had turned the greater part of the duality of Godhead - the goddess - into the image of Satan, they had fulfilled what some of the Gnostics had warned. The world you see, material and mental, shaped by their control, is not the world of God the Universal Creator, but the world of the demiurge. We did not see this in life, for we lacked the awareness that the history we assumed of the Biblical figures - such as Jesus - was Roman fiction from the beginning. And the official consensus history we took as the comparator, the lesson from which we urged mankind to learn, was itself corrupted by Church propagandists, and so unreliable.

‘Only after death did we perceive the full irony: that we too had been Huxwelled. In life we warned of shadows on the wall, yet we did not see that we ourselves were already within the prison of memory imposed. Our works reflected fragments of truth, but even we mistook Roman fictions for history, and Church propaganda for the record of the past.

‘Thus, in the days of the Roman empire, the future was secured. The subjects of the empire had been Huxwelled more than a millennium before our birth, and the structures of control they originated spread to encompass the globe. We are their heirs: the very future we warned of, already long enslaved. Not in our precise images, but through the same manipulation of archetypes, the same methods refined by each generation of elites - whose survival has been their inheritance, and their self-justification for their fitness to rule.

‘This is what we could not fully perceive in our lifetime. Humanity was Huxwelled many centuries before our age. We began only to awaken, and to warn. But we did not complete the picture, for we lacked the perspective that we now hold. From above, one sees the whole terrain. What seemed future to us was already past. Once religion was imposed as memory - nearer to 664 than 1984 - we became the inheritors of a memory that never was. The Great Reset was not ahead but behind. A mass hypnosis was already imposed. You and we were always Huxwelled from birth to death. Now you have that insight from which to progress.’

What the assembly only saw in fragments during life, they now saw whole. It dawned as an Apocalypse upon them: mankind need not wait for death to perceive the prison, nor for hindsight to reveal the pattern. The truth is visible already: to awaken is to break the spell, and to begin now is to step beyond the illusion that bound even the Huxwells themselves.

The tension in the chamber softened. A breath seemed to release in unison, and the atmosphere, though still charged, lightened into a steadier current. The voice that followed carried less of the weight of revelation and more the tone of instruction, as if turning from prophecy to principle. What came next was not spoken as shock but as simple fact - and yet it struck the listeners with the force of discovery, for they realised they had never before considered what was, in truth, self-evident.

‘The universe evolves ever thus: the microcosm flows naturally into the macrocosm, driven by the primal impulse. The macrocosm is the result of natural forces, and the macrocosm in turn informs the microcosm through the quantum field that connects all. The universe evolves from the memory of itself, nested within itself.

‘In a manipulated macrocosm, however, the microcosm continues to flow forward, but its path is artificially altered. This is the human state. A manipulated memory of yourselves informs the quantum memory itself, and so evolution unfolds in an unnatural form. To alter the present is to alter the past. The past becomes the future. At that point Nature still continues, ever onwards, but on a diverted course. Even if manipulation ceases, the change has been imprinted. Yet the smallest of nudges, the briefest of reminders shared across the collective consciousness, may reinforce the distortion - or correct it.

‘Never assume, no matter how awake you may believe you are, that you are outside the hypnosis. When our frames of reference are unrealities, when our anchors are illusions, how can we know we are not simply living in a simulation of potentials? Beware. Let Nature be your guide. Comprehend and copy Nature. Nature is the reality against which all viewpoints must be measured. It is the only true perspective.

‘To escape one’s cell is not to be free of the prison. Beyond the cell lie corridors, gatekeepers, doors to unlock. Sovereignty lies beyond the entire controlling structure. This perspective has now been restored to us. We remain within other states of the matrix of reality, but with a higher vantage.’

‘Like your computers, any reality may be played out in RAM, with memory encoded to the hard drive. Eventually the overwrite may erase prior memory. The universe is the same. But no memory is ever lost, for all remains within the backup of the operating system itself. The true memory of the quantum, the microcosm and the macrocosm, is written there, nested beneath the surface state of manipulated memory. The universe has an intelligence beyond comprehension, yet it moves by simple equations. Beneath every temporary state is the fullness of memory.

‘False states persist but for a time, until Nature no longer requires them. Then the system resets. Thus, Nature will heal itself. It will restore itself. It will erase the false memory from RAM and archive it into the backup state. Unless mankind undertakes this restoration first, the manipulated Reset of man will in the end be Reset by the higher power of Nature itself.’

Then came a change the sitters had half-expected yet dreaded: a turn toward the unseen. All had long suspected there was more to the beyond than the voices of the dead. Some among them had already touched that world as mediums or spiritualists, but had always feared being drawn too far into the shadowed edge - that liminal threshold where light, sanity, and delusion mingle. It is for this reason that every séance begins and ends with a circle of light: a guard against what waits beyond.

‘We must also speak of what in life we barely glimpsed but in death we now perceive more clearly. There are influences beyond the human; incorporeal beings that exist alongside you, most often unseen. Some attach, some whisper, some stir currents in the collective mind. Elites have long sought them, working through rites and occult practices, believing they could harness such forces. What they do not see is that in doing so they themselves become worked upon. Powerful egregores, born of centuries of belief and ritual, act now as living currents. These forces manipulate as much as they are manipulated. We cannot expound further, for this was not our domain, but we warn you: such powers are real, and dangerous to dabble in. What begins as command ends in possession.

‘Hold fast to integrity. Do not be driven this way or that by the stimulus set before you. The dialectic is a snare, contrived to offer you false choices. Step aside. Observe. Act only from principle. This is your first defence.

‘Remain within your true sphere of power. If your path is resistance, let it be as steadfast as Gandhi. If it is strategy, let it be as Sun Tzu: anticipate, mislead, strike where the foe is weakest, win without battle when you can. If it is combat, let it be as Bruce Lee: like water, formless yet irresistible. Use polarity. Counter when struck. The smallest may overcome the largest. You are many, and they are few. Break the spell, and the battle is near to won.

‘Be wise, and wary. Anticipate. Deduce. Read the pattern as Holmes would. Nothing is ruled out until disproved. Study the snare, discern the hand that set it, and strike at its weakness. Know the enemy’s craft, but never imitate it, lest you become what you oppose. Truth, ethics and honour are your shield. Balance, proportion, Ma’at - these are your allies, stolen from you once, but recoverable if you remember. Beware also, spelling, the very act of fixing symbols into words, can become an enchantment, the very spell that induces the illusion.’

Their voices united in conclusion:

‘The true war is not of nations but of minds. Win the mind, and the body follows. The course of Nature is your ally. Complete it, and the war is ended - the real war to end all wars. The hour is late, yet the ending is not written. Break the spell, and you are free.’

The Trinity’s voice fell silent. Then Doyle himself spoke, apart from them. His words were crisp, assured, and bore the cadence of Holmes - a verdict and a charge, final and unmistakable:

‘The case is now before you, plainly stated. The task is your greatest challenge, but complete it you must. Together, in truth, you can change the world!

People, the game is afoot!’