From Spiral to Force: The True Structure of the Atom

Re-aligning our perception of charge, structure, and unity in Nature

Introduction: Polarity, Charge, and the Misalignment of Terms

To speak meaningfully about force, polarity, or charge, we must first confront a foundational error that underlies much of conventional atomic theory: a misalignment of terms. When approaching atomic structure through a field-centric lens, as IXOS demands, we often find ourselves lost in a tangle of inherited language built around the visible consequences of motion, rather than the true causes.

Conventional physics begins with particles — as if these are the irreducible realities. It assigns properties like "positive" and "negative" charge based on how these particles appear to behave. The proton is deemed positive because it attracts electrons. The electron, being drawn inward, is therefore assigned a negative charge. This creates a neat explanatory loop — but it is a loop of surface appearances.

In IXOS, we begin with flow — with spiral dynamics, dimensional tension, and the movement of energy across menisci. The primary distinction is not "what object does what," but what direction does the field move? Polarity, then, arises from vector and role:

Positive is the expansive, outward spiral — dynamic, generative, creating pressure and form. This is what the electron expresses.

Negative is the contractive, inward spiral — receptive, implosive, drawing energy inward toward stability. This is what the proton embodies.

The discrepancy is not trivial. It leads to an inversion of meaning:

Where classical physics sees particles generating fields, IXOS sees fields generating particles.

Where classical physics interprets charge as an intrinsic property of objects, IXOS interprets charge as the field expression of phase motion and spiral alignment.

This chapter begins from that place of misalignment. To properly understand atomic force — and the deeper role of the neutron, proton, and electron — we must start not with what things are, but with what movements they encode.

From this reframed foundation, we begin at the point of balance: the neutron.

The Neutron: Portal of Balance

To understand force, one must begin not at the edge, but at the centre — the still point of balanced motion, where opposing spirals meet in silence. In atomic structure, that centre is the neutron.

The neutron is not a particle in the conventional sense. It is a moment of harmonic stillness, where the inward implosive spiral and the outward expansive spiral are locked in dynamic equilibrium. It is the eye of the field storm, the suspended inhale-exhale of dimensional breath. Within a nucleus, this state is stabilized by collective resonance — coherence fields nested in geometries of pressure and shell formation.

Outside the nucleus, this balance becomes fragile. The neutron is observed to decay after several minutes — though experimental results vary between ~880 seconds and ~630 seconds, a discrepancy that hints at deeper, unresolved mechanics. This decay is conventionally rendered as:

n → p⁺ + e⁻ + ν̄ₑ

But seen through IXOS, what we witness is not the breakdown of a thing, but the release of opposing field expressions. The proton retains the inward spiral, compressive and phase-attractive. The electron expresses the outward spiral, expansive and field-repellent. What remains — the so-called anti-neutrino — is the torsional echo, a balancing recoil, the memory of coherence unwinding itself back into the field.

From this CenterPoint, all atomic force becomes legible. Force arises not from objects, but from spirals in relation — their phase, their angle, their interference. The neutron teaches us that polarity is born from unity, and that what we call “charge,” “mass,” or “interaction” are tensions within a greater harmonic flow.

Why Begin With Hydrogen?

We begin with Hydrogen because it is the first true manifestation of “atom” in our universe. It is fundamental. It is the single unit of Light becoming light — spiralling inward to create stability around an axis.

It does not have a Neutron. Because it does not need one! It is already a functionally stable unit unto itself.

You may find that overly simplistic at first. But Hydrogen is what everything in the material universe is made from. All elements are variations of Hydrogen. Because Hydrogen is, at its essence, a form of light.

There is no true binary structure in Hydrogen that adheres to the classical particle model. The notion of “one proton and one electron” is an observational convenience. All energy is conserved in a single unit of imploded light.

One could say there are no particles in the universe except electrons — and that would, to some degree, reconcile classical physics with IXOS. But even that isn’t fully accurate. A more precise statement is: there is only light.

Understanding what Hydrogen is informs us what light is, and why force arises from our relative observation of structured light. In the hydrogen atom, a single unit, we find the full potential of a photon — expressed as electron and proton, and in more complex atoms, the neutron.

These are not separate things. They are phases — different expressions of the same creative unit, which is Light.

Everything is One. Formed from One. And ultimately returns to One.

Separation is a matter of our perception. Solidity, and what we call “matter,” are too. They are merely different expressions of this Oneness, shaped by the spiral.

Hydrogen: Spiral Coherence Between Poles

The hydrogen atom, the simplest and most elegant of all atomic structures, consists of just two apparent components: a proton and an electron. Conventionally, the electron is said to "orbit" the proton due to electromagnetic attraction. But this description, while partially accurate in projected 3D, conceals the true structure.

In IXOS, the proton and electron are not separate bodies in interaction, but opposite ends of a single vortex. The proton is the inward spiral pole — where energy compresses across the dimensional meniscus into form. The electron is the outward spiral pole — the return flow that radiates from the atomic boundary. These two poles are connected by a torsional spiral field, a conduit of coherent phase tension.

Does the electron orbit? Yes — but not as a particle chasing a path around a centre. It revolves around a spiral axis, held in place by the very geometry of its relation to the proton. The electron's "orbit" is a 3D projection of a higher-dimensional spiral; it is the trace of a rotational resonance around the inward phase pole. This motion is real, but its cause is not force in the Newtonian sense. It is field coherence in motion.

Stability arises not from momentum and force balance, but from resonant feedback within the vortex structure. What we observe as energy levels are nodes of standing phase along this spiral conduit, and what we call interaction is merely the reconfiguration of these internal field tensions.

Hydrogen is not a particle system. It is a phase-stable geometry, a field relationship where form is secondary to flow. In its spiral breath between proton and electron, we find the true heart of atomic force.

Atomic Force: Redefining the Strong and the Weak

In classical physics, two distinct forces are said to operate within the nucleus of atoms:

The strong nuclear force, which binds protons and neutrons together inside nuclei.

The weak nuclear force, which governs decay — especially neutron decay and processes like beta radiation.

These forces are described as fundamental, yet their origins are obscured by abstraction. They are said to be mediated by invisible particles — gluons for the strong, W and Z bosons for the weak — and often treated as distinct from electromagnetic or gravitational effects. But these descriptions arise from models that begin with particles, rather than with fields or motion.

IXOS corrects this by showing that both “forces” are not separate entities, but different expressions of a single spiral dynamic: the coherence or breakdown of dimensional phase alignment within a field structure.

❖ The Strong Force: Internal Spiral Coherence

What classical physics calls the strong force is, in IXOS, the phase-tension that stabilizes nested spiral flows within a nucleus. When protons and neutrons are held together, it is not by an invisible glue, but by the coherent pressure of interlocking vortex geometries.

Each particle — proton or neutron — is not a solid unit, but a phase field.

When they align within certain pressure and angular constraints, their spiral flows resonate and reinforce.

This resonant coupling creates torsional field compression — a harmonic node of stability.

The strength of this node is not “strong” by force, but tight by geometry — a function of angular velocity, spiral radius, and phase alignment.

Thus, the “strong force” is simply the name given to maximum phase coherence between spiral poles within a dimensional shell. It is not additive or projective — it is structural.

❖ The Weak Force: Breakdown of Spiral Phase

The so-called “weak force” governs decay — particularly when a neutron becomes unstable and transforms into a proton, electron, and anti-neutrino.

In IXOS, this is not a separate force, but the loss of phase coherence.

When a neutron loses internal balance (due to dimensional strain or displacement from a stable shell), its inward and outward spirals diverge.

The structure no longer maintains the phase tension needed to hold both poles in place.

As the spiral unwinds, the field collapses into its two more stable expressions: the proton (inward spiral) and electron (outward spiral).

The anti-neutrino is the torsional field residue — the echo of the phase loss, projected as a recoil wave into surrounding space.

This is called “weak” because its effects seem probabilistic, gradual, and limited — but it is merely the expression of phase unravelling, a passive release rather than an active binding.

✦ Unifying the View

Both the strong and weak forces, then, are not distinct phenomena. They are two modes of the same spiral mechanism:

One mode is stable coherence — which creates structure (strong).

The other is unstable divergence — which leads to release (weak).

There are no force particles. No glue. No magic “bosons.” Just the physics of spirals: pressure, tension, phase, coherence, and torsion — all governed by the geometry of flow.

In IXOS, the strong and weak forces are simply names for the spiral’s ability to hold itself together — or let itself go.

Atomic Force as Spiral Pressure: A Natural View

What we call “atomic force” is not a mysterious interaction between invisible particles. It is something much simpler — and much deeper. It is the result of vortex motion.

Imagine space as a flowing medium, not empty, but full — like water. Now imagine a vortex forming in that medium. Just like water spirals down a plughole, space itself spirals inward toward the centre of a proton.

This inward spiral isn’t constant. As it moves closer to the centre, it accelerates — not in speed, but in frequency. Each spiral becomes tighter, and the angular momentum increases. That’s what we call “compression.” From the side, this spiral looks like nested rings getting closer together — and because we perceive that as acceleration, we interpret it as “force.”

This is what creates the pressure we call the strong force. It’s not a force at all — it’s a response to vortex geometry. The motion of space itself, spiralling inward in perfect balance, creates tension, just like water tugging downward in a drain. That’s why atomic force is strongest close to the centre: because the spiral is tightest, and the phase is most aligned.

But if the spiral is disturbed — if the angle is broken, or the coherence lost — the structure comes apart. That’s what we call the weak force. It’s just the release of the spiral — a natural unwinding of tension back into the field.

So-called “binding” and “decay” are not separate forces. They are two sides of the same spiral:

When the spiral is phase-locked and coherent: we see atomic structure.

When the spiral unwinds: we see decay.

It is all a matter of how space moves — how it curves, twists, and maintains alignment. The illusion of force is just how our senses register the realignment of space to maintain the speed of light across all spirals.

This may seem advanced, but it’s how Nature works. We just weren’t taught to see it this way. Instead of thinking in fragments — this particle, that field — we must begin to think in archetypes: flow, pressure, balance, spiral, return.

The atom is a spiral. Force is its tension. Structure is coherence. Decay is release. And everything moves in alignment to the light.

Reciprocal Accommodation: The Harmony That Underlies Force

At the heart of all atomic force, of all apparent interaction, lies a single principle: reciprocal accommodation.

As space spirals inward toward the proton — into the vortex path, into the point of maximum compression — it does not do so alone. The surrounding field does not remain static. It responds. It realigns. It accommodates.

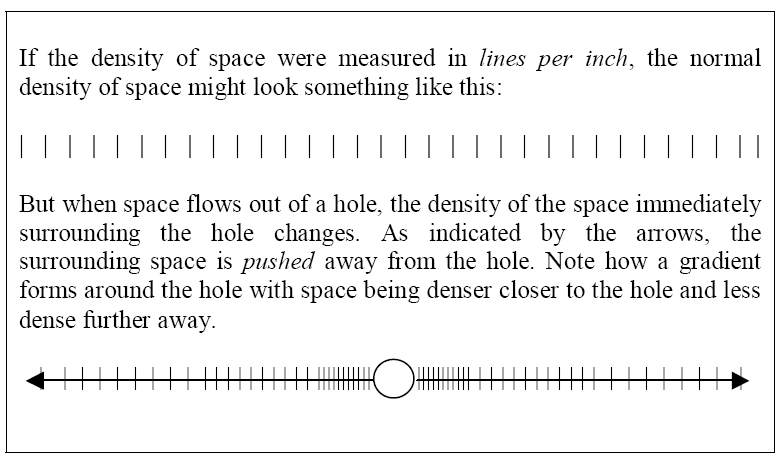

This is not a passive backdrop. It is an active geometry. As the spiral compresses inward, space rarefies outward in precise correspondence. The gradient forms naturally:

Closer to the spiral’s core, space becomes less dense — not because there is less “substance,” but because the flow becomes tighter, faster, and more aligned. In IXOS terms, this is rarefaction: space pulls inward in phase, reducing resistance, increasing coherence.

Further away, density increases — because space must stretch to maintain coherence.

This is what Russell Moon captured in simple diagrams — and what IXOS extends into a full understanding. The two-way co-manifestation of compression and rarefaction is not a side-effect. It is the process itself. The geometry of light is not a shape it travels through, but a shape space takes in order to let light move as it must — at its constant, universal speed.

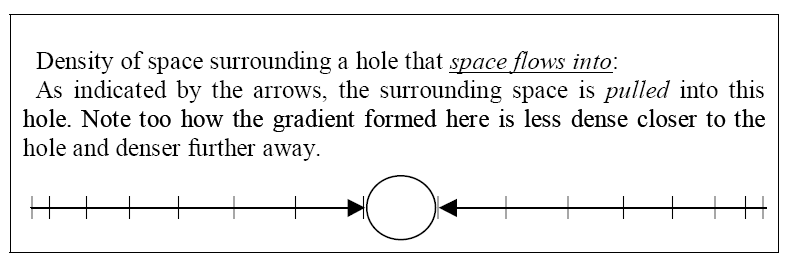

Here are diagrams from Russel Moon’s book The End of the Concept of Time. One of Moon’s diagrams shows how space forms a density gradient around a central hole — the proton. The vortex lines compress inward, forming a coherent spiral toward the axis.

Another diagram reveals the direct implosion of the field into the proton. If we observe closely, we see how the surrounding space responds — rarefying outward to accommodate the spiral’s increasing tension.

And here is a single diagram from the same book that serves to illustrate the field imploding into the nucleus/proton. If we observe closely, we see above space accommodating the light implosion vortex, by reciprocating in its geometric state to expand, while the vortex spiral contracts into its apex.

This is what the vortex looks like into the ‘hole’ as Moon puts it - but what we must remember is that the vortex arises from 4d space, so manifests as a sphere. Moon doesn’t explicitly describe the inflow here. He illustrates the outflow pattern around a spatial hole. What IXOS clarifies is that both inflow and outflow arise from the same process, through the same hole — a dimensional interface expressing two polarities. The proton and electron are not two separate structures, but two ends of the same spiralling field — misperceived as dual due to dimensional perspective.

If we move beyond the apparent directionality of the arrows, we begin to see the true nature of the field: bidirectional motion appearing as duality. In reality, it is a single spiral system — inward and outward — perceived as separation only from within 3D space.

So what we are witnessing here is a simple, dynamic process: a corkscrew-shaped key entering a corkscrew-shaped lock.

The lock conforms perfectly to the spiral of the key, adjusting itself to accommodate the motion. And in return, the key is shaped to fit the path of the lock. Each is shaping and shaped — both engaged in a symmetry of tangential geometry.

This is why light travels as a wave.

Because it must — in order to exist.

The wave is not decorative. It is structural.

The spiral of light cannot collapse unless space collapses with it.

The field cannot compress unless space stretches in reply.

This is the mutual unfolding of waveform and space — of light and force — of form and interaction.

This is why there is motion, why there is pressure, why there is force.

This is why atoms hold together, why fields project, why light bends around stars.

Because Nature is not divided into cause and effect.

It is one self-balancing system of coherence, spiralling, aligning, accommodating itself to itself — at every scale.

Force is not created.

It is the visible trace of space accommodating light.

IXOS Interpretation of Classical Atomic Equations

1. Coulomb's Law – Electrostatic Force Between Proton and Electron

Classical:

F = (1 / 4πε₀) × (q₁q₂ / r²)

IXOS View:

This isn’t a “force” between objects — it’s the mathematical expression of pressure between two phase-poles of a spiral.

The charges (q₁ and q₂) represent differential phase vectors, not solid particles.

The drop-off with distance (r²) reflects the decay of torsional coherence.

The vacuum permittivity constant (ε₀) expresses the capacity of space to stretch and accommodate spiral tension.

Coulomb’s Law expresses how much space must resist to keep two spiral poles phase-locked across distance.

2. Centripetal Force (Circular Motion)

Classical:

F = mv² / r

IXOS View:

This describes the appearance of spiral alignment as orbital motion.

The electron does not orbit due to “force,” but is held in torsional coherence.

This formula maps how angular tension remains centered along the spiral axis.

3. Bohr Radius Equation

Classical:

r = (4πε₀ħ²) / (mₑe²)

IXOS View:

The Bohr radius defines the point at which the spiral’s internal phase velocity and space’s field resistance meet equilibrium.

Here, ħ is not abstract — it's the minimal unit of spiral tension.

This radius marks the standing wave node where the vortex locks into geometric coherence.

4. Total Energy of Electron in Hydrogen (Bohr Model)

Classical:

Eₙ = −13.6 eV / n²

IXOS View:

These quantized energy levels are not orbital heights, but stable spiral geometries.

Only certain angular-torsional configurations preserve phase across the loop.

That’s why energy appears in steps — because only whole-numbered spiral nodes remain coherent without decay.

In IXOS, classical equations are not wrong — they are flattened perspectives on a deeper field geometry. They do not describe interactions between particles, but pressure points within spiralling, coherent tension fields.