Return of the Storm God - Chapter 8b

Including the anthropological roots of religious misogyny and the suppression of women.

Restoring the True Meaning of Pythagoras: The Path to the Origin of Light

Consensus tells us Pythagoras was a man of Samos. A mathematician. A mystic. A cult figure who believed in number and harmony. That much is admitted as possible, but not proved. The man remains elusive - more shadow than source. But if Pythagoras was any man of the 6th century BCE, he must have been entitled thus, not named so - the leader of the Pythagorean cult, not its origin. And therefore, more than a single man.

Even the syllable ag in his name implies leading, guiding, or moving toward - it is the root of agency itself. In this light, Pythagoras therefore symbolically means ‘the Leader of the Path of Pyth’ - a title denoting the one who walks and teaches the serpent path, the harmonic spiral of Phi, toward the origin of light. That is, the Ag of Pyth to the Or of Ra. The name is not a Greek invention, but a Greek retention of a much older Egyptian encoding - one that veils, yet preserves, the feminine source within the axis.

But ask any mainstream linguist, academic historian, or AI trained on consensus material about the deeper origin of this name - about its connection to Egyptian cosmology - and they will tell you it is coincidental. Always coincidence. Never continuity.

Their logic is governed by the presence of formal documentation. If no direct lineage exists in the available records, then it is assumed not to be so. But this is a flawed foundation. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence - especially in cultures where secrecy was sacred, where initiatory orders protected knowledge through symbolic layers, and where written traces were either concealed, destroyed, or never committed to perishable record in the first place.

Nor does this academic presumption account for the systematic redactions of history, the political destruction of texts, or the institutional hoarding of counter-narratives. The most obvious example remains the Library of Alexandria - a vast compendium of ancient knowledge, of which we do not know how much was lost, nor to what extent its destruction was accidental, political, or deliberately orchestrated.

It is entirely within the bounds of reason to assume that what threatened the imperial or ecclesiastical status quo was removed. And what could not be removed - was recast, veiled in scripture, or buried in vaults. To this day, the Church’s archives remain sealed to all but the highest ranks - thousands of years of written record locked away from public scrutiny.

To ignore this context is not scholarship. It is dogma under a scholarly name.

Yet ask a Pythagorean initiate - one steeped in the sacred function of number - or a high-degree Freemason familiar with the symbolic architecture of the axis, and you will find full recognition of what I now assert, at least none of them will deny its plausibility and logic:

The name ‘Pythagoras’ is not a personal identifier. It is a title. A symbolic sentence encoded with cosmological intent. It means: ‘The one who moves through serpent wisdom (Pytha) toward the origin of light (Ag–Ur–Ra).’

This is the very definition of the phrase ‘path to enlightenment’ inherent in every religion and philosophy known.

This is not poetic speculation. It is rooted in linguistic morphology, symbolic recurrence, and sacred function. It is not ‘folk etymology’ - it is the original encoding of knowledge by those who understood that language is a vessel, not just a code.

Let us break it down structurally:

The Word: PYTH–AG–OR–AS

Pytha (Putah/Ptah) - The Egyptian Father and creator principle of utterance, shaping, and speech - the form-bringer, the Word utterer – the Logos. But also Pyth, the veiled serpent at Delphi, beneath the omphalos. The breath before the Word.

Ag - To move, lead, or initiate. Found in agō, agni, and all words of action and transmission. It is the path.

Ur / Or / Ra - The source. The flame. The original light. In Sumerian and Egyptian, Ur is the city of origin, and Ra is the visible light that emerges from it. The origin of radiance.

Agora (Greek: ἀγορά) - Conventionally translated as ‘marketplace’, but in structure and function it means ‘the coming together’ - the convergence of the many onto the one. The very function of the Djed, the cross, the axis, the omphalos - all symbolic centres of alignment.

The Agora is not only a meeting or a marketplace. It is the ritual convergence. The place where the field lines meet, where the axis stands upright, and where - within the pillar - is concealed the goddess: Isis veiled.

In ancient Greece, an ‘agora’ was a central public space where citizens would meet for commerce, political debate, and philosophical discussions.

It is the point of sacred assembly, where the many converge upon the One, where heaven touches earth, and the breath of the unseen moves through the centre. The Agora is the meeting of any cult or priesthood dedicated to a deity at the ritual axis site: the Omphalos at Delphi, Tara in Ireland, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, the ziggurat of Babylon, the pyramid of Giza, the Benben of Heliopolis - even the altar of a church. All are iterations of the same principle: convergence upon the veiled centre. The meeting place is not geographical - it is geometric, harmonic, symbolic. The Agora is the gathering around the Djed, the joining of the cross, the entry to the Duat. And within it stands the axis, and within the axis - the goddess, whose breath animates the Word.

Pythagoras is The Initiate of the Converging Path

He is:

The walker of the axis – a medjed in function

The one who follows the tetractys - 1, 2, 3, 4 = 10 - the path from unity to manifestation and back again

The servant of Phi, the golden proportion

The heir of Isis, the one who guards the mystery of the origin through veiling, not obscuring

The Pythagoreans were not simply numerologists or Greek mystics. They were initiates - high-level mathematicians and philosophers sworn to secrecy - and their core tenets were drawn directly from Egyptian typology. They meditated daily upon the Tetractys, the sacred triangular figure comprising ten points in four rows (1–2–3–4 = 10), which encoded not only arithmetic harmony but the very architecture of creation. The Tetractys was not abstract geometry - it was cosmology, symbol, and soul-structure all at once.

They also believed in the transmigration of the soul - the cycle of rebirth through successive lives - a doctrine entirely consistent with the Egyptian model of the ba (soul) and ka (life-force) undergoing purification and return through the Duat. This was not Stoic ethics or Platonic idealism. It was a direct echo of Egyptian metaphysics, where the soul journeys through trial, measurement, and restoration before ascending to unity with the divine.

Every principle the Pythagoreans held sacred - number as living force, soul as eternal, harmony as law, and secrecy as duty - can be found already encoded in the Egyptian priesthoods of Memphis, Thebes, and Heliopolis. This was not Hellenistic invention, but Hellenic transmission of an older system. What they called the Tetractys, the Egyptians already encoded in the Djed, in the geometry of Saqqara, at Giza, and in the very naming of the gods.

Pythagoras, whether historical or archetypal, stood at the threshold of that transmission - not its source, but its inheritor.

Ask Yourself: Who Should We Trust?

Ask an academic linguist or etymologist who relies on consensus derivations such as PIE, and they will tell you this is all a web of misreadings. Coincidence. Backformation. Mistaken comparison. Poor ‘dot connecting’ through confirmation bias. A ‘conspiracy theory’ even.

But ask a Pythagorean - an initiate of the tradition that built the Western canon of number, form, harmony, and proportion - and they will affirm it. They have always known this was the origin of the name. It was encoded, not declared. Hidden in plain sight.

Ask a Freemason, high in the degrees, who has worked through the rituals of the cross, the axis, the Word, the veil - and they too will affirm it. The pillar, the python, the convergence - all encoded within the name.

I remind the casual reader - particularly those unfamiliar with the world of secret orders and initiatory guilds and their symbology - that many of the front-facing figures of historical significance were not simply political or religious actors, but also initiates of esoteric traditions. The Founding Fathers of America, for instance, were not merely Christians; many were Freemasons, steeped in archetypal thinking, symbolic logic, and occult correspondences. Their worldview was shaped by systems of meaning that emphasised mythic structure, numerical resonance, linguistic depth, and ritual geometry - not unlike the framework we are restoring here.

What we are doing, then, is not abstract speculation, nor mere play with words and numbers. We are reconstructing meaning using the very symbolic logic that these orders, priesthoods, and institutions themselves preserved - and which have been encoded into architecture, scripture, law, and language across millennia. This is the mode of interpretation used by those who have shaped the trajectories of religion, royalty, commerce, and empire. We are not departing from history. We are reading it through the lens its makers used - not the one their institutions later imposed.

And yet academia, trained on 19th-century philological rules designed to serve imperial and ecclesiastical needs, will never admit this. They deny Isis, the original harmoniser. They deny Phi as the golden ratio embedded in all life. They deny the serpent of wisdom, the cobra of Wadjet, who sees from above and guards the brow of divine insight. They deny the feminine, because the Church demanded it - because Rome could not tolerate a cosmos governed by balance, water, measure, and restoration. They deny the existence of the soul outside of the body because to admit it would restore meaning to those cultures that have accepted it and which do not endorse religious dogmatism or narrow-minded and unnatural man-made systems.

But when KRST is revealed in its true form - not as a crucified male saviour, but as the ancient Egyptian typology of the soul of Osiris, the corpus kar (the hard, dry hydronymic form) - anointed by the sacred waters of Aset (Isis), the ‘st’ that completes and vivifies the body - then the entire Judeo-Christian narrative – their appropriated pyramid of deception - comes tumbling down.

We have already proved the entire story of Jesus to be thousands of years older than the Gospels, and almost entirely Egyptian.

The further distorted myth imposed as history is unveiled as fabrication (the woven cloth from the twisted flax – which I will explore later) - its structure inverted, its centre hollow. The sacred name KRST, once a theanonym - a divine compound denoting the anointed field-body, resurrected through the balance of masculine form and feminine waters or oils - became devoid of meaning when Rome transformed it into Christ, a male-only title severed from its source. What had once been a symbol of sacred polarity, of kar (the dry, inert form) brought back to life by st (the sacred waters of Isis), was reduced to a theological slogan - emptied of function, stripped of the goddess, detached from the field.

But when recovered in its full symbolic frame, KRST still stands as a poorly disguised theanonym - not a man, but a structure. Not a saviour, but a state of resurrection through balance. It encodes the eternal law: that life is restored only when the masculine is anointed by the feminine - when the dry is made wet, when the word is made fertile, when the pillar is raised by the veiled power within it. When form is given the life breath – HU restored through the ankh of the goddess and god as one.

The name was never lost. It was only veiled.

With the sacred feminine restored as the animating power behind the resurrection - the veiled force behind the axis - the very pillar upon which Christianity was built crumbles into dust. Because it was never theirs. The Djed was Isis's. The anointing waters were hers. The path through the Duat, hers. The KRST was always the anointed field-body - not a man, but a structure restored through the feminine.

And when this truth is remembered - not theorised, but embodied, and re-aligned - the spell breaks.

Ask them why the pentagram within the circle - a shape constructed entirely from the golden ratio of Phi - was the very sign for the entry into the Mother’s Womb. The symbol of the Duat (or Tuat) - the Egyptian underworld, which is not a realm of punishment, but the sacred space of initiation and reconstitution. It is the place where the soul begins its journey, is measured in the scales of Ma’at, and must pass through the gate of the goddess’s geometry - the Phi-ratio that defines the pentagram.

This sign was not obscure: it was carved into tombs, drawn on star charts, and later survived as the Duat symbol in Gardiner’s lexicon - a pentagram within a circle. The sign they made into a symbol of evil and satanic witchcraft. In English vulgarisation Tuat becomes twat - the veiled mockery of the Tuat, the gate of the sacred feminine. In Irish it echoes as Tuat and Tuatha - the People of the Goddess Danu, children of light and field structure. What was once the womb of origin and spiritual return was somewhat degraded into obscenity, erased from sacred memory, and severed from its cosmological function. This is not etymological drift. This is symbolic inversion; rendering the sacred profane.

Ask them also why there are so many ‘coincidences entirely unrelated’ in the culture of the Celts and the Culdees, those who gathered in cells - like early monastic star-chambers - to contemplate the mysteries of the cosmos. All beginning with cel/cul/chal hydronyms.

Ask why the Tuathian inheritors of the Chaldean wisdom traditions revered the Mother as Water, as ethereal flow, not terrestrial possession. Ask how it is that the sacred lineages of Danu, Anu, and Inanna - all ancient mother goddesses of light, water, and fertility - are so evidently present in Ireland, Scotland, and the Hebrides, not as cultural borrowings, but as the living substratum. Inanna, whose cult included the Gala priests - and whose sacred language was ceremonial, ritual, hydronymic - somehow gives rise to a people thousands of years later whose own high spiritual language is still called Gaelic (pron. Gal-ik). A language formed not arbitrarily but from hydronymic, luminymic, and theanonymic roots. A language flowing like water, like a river or gala filled with light-words and god-names. A language that remembers. This is not claimed as evidenced by direct lineage in linguistic terms, but as a typological echo within the Drift Culture memory stream, wherein the evidence may have been removed deliberately by certain vested interests to obscure it. For, where consensus academia says coincidence, we often see continuity.

We are told this is all coincidence. That there is no relation between Gala and Gaelic. No connection between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the ancient Chaldeans. That Danu and Anu are localised Celtic inventions, not preservations of the primordial Mother and Father called Inanna and Anu in ancient Mesopotamia. That the Culdees - the hidden spiritual fire-tenders - were Christian monks and nothing more. And that the sacred cells they inhabited - like those of Egypt, like the hermetic stone huts of Skellig Michael - were architectural necessities, not resonant chambers of cosmological silence of the ancient shamanic traditions.

But the truth is already known to those who have ears to hear it: this is not coincidence. It is continuity. The Mother never died. Her names flowed westward. Her water carried her wisdom. Her serpent lit the stars. And her priests - the Gala - simply changed tongue, evolved into new ritualistic forms, became localised to the Irish environment. Gaelic is not just a dialect or indigenous language. It is a sacred Drift Culture language, encoded with the breath of the Source, that retains a memory stretching back thousands of years.

To the Romans, this ancient Pythagorean cult - with its reverence for number, rebirth, harmony, and the veiled goddess at the centre of the axis - was anathema. It stood as a direct threat to the imperial worldview. Just as they did with the Celts, the Druids, the pagans of Gaul, Albion, and Hibernia, the Romans sought to denigrate what they could not control; so they absorbed it, branding the original as uncivilised, primitive, and chaotic in contrast to the supposed apex of order and reason: Rome. But what Rome brought was not an egalitarian communal civilisation - it was systematised domination, enforced through military conquest and theological inversion.

They had to paint over the older cultures, to dismantle their symbols, to mock their serpent wisdom, and above all, to replace their feminine-rooted balance with a centralised male figurehead - a god-man made in the image of empire. This new myth, crystallised centuries later as the Christianised Jesus, served Rome’s needs perfectly. Through it, they created a theology of hierarchy, guilt, salvation, and reward that fed the Roman machine. The land, once held as sacred gift by indigenous peoples, became taxable. The fruits of the Earth, once offered in rites of gratitude to the Mother, were now given to Rome through tithes, conquest, and economic servitude - justified by divine right.

In the name of Christ, they seized harvests. In the name of civilisation, they burned the oak groves. They also tortured and burned the people into submission – Christ or death through torture was the choice given. And in the name of the male god, they buried the memory of the goddess - in language, in law, in stone, and in time. But memory lives where truth was never destroyed - only veiled.

And when they were caught in their lies, they justified them as necessary. They were not deceivers, they claimed – they were pious frauds, practitioners of a necessary evil.

‘It is an act of virtue to deceive and lie, when by such means the interests of the Church might be promoted.’ - Ecclesiastical History, Bishop Eusebius

(A man whose ‘history’ is still cited by consensus academics as a reliable source of factual data.)

Holy strategists. Liars for God. They forged gospels. They fabricated letters from biblical figures. They invented saints, manufactured martyrdoms, and rewrote myth as history – all, they claimed, to save souls. An unfortunate but necessary deception, they said, to bring the ignorant masses – the children of God – into the fold. The ends justified the means. The flock was too stupid, they believed, to find truth within their own conscience, and so had to be tricked into salvation.

But what they saved was not the souls of the flock. What they preserved was their own power. What they harvested was obedience. And through obedience, they took all the most valuable worldly goods – gold, grain, land, minerals – and returned them to the Mother Church under the guise of divine right.

We are not asserting that any individual does not have the right to believe whatever they wish, nor to find solace, structure, or spiritual comfort in those beliefs. But no person – and certainly no institution – has the right to insist, against all evidence, that their belief is unchallengeable truth. And they most certainly have no right to impose that belief upon others – to mandate it, legislate it, or use it as a tool of persecution.

There exists more than enough evidence to demonstrate that organised religion was founded upon a mountain of lies – and that many spiritual dogmas, often presumed to be sources of inherent morality, are in fact constructs built upon deception. That is not to say there is nothing of truth within religion. Much is morally valid, symbolically powerful, even archetypally resonant. But far too little survives intact to justify the colossal delusions that have been wrapped around these fragments – and passed off as divine truth.

Not all of these lies were recognised as lies in their own time. The redactors, clerics, and chroniclers of the Church wrote for a largely illiterate and parochial audience, one unprepared for the revelations of future centuries – for the sands of archaeology, the proofs of carbon dating, the evidence of genetic science, the comparative analysis of myth, symbol, language, and cosmology. Those future discoveries did not concern them. Their only concern was service to the masters who sought to maintain their place atop the social and theological pyramid.

Respect the right to believe. But never respect a belief that is demonstrably false. No one should be expected to defer to fiction out of politeness. Especially not academia. The line between what is true and what is false, what is possible and what is not, and what is probable versus what is convenient – must be drawn. It must be expressed with clarity. And it must be defended.

We follow the evidence here – and let the evidence speak for itself.

Because now, as the veil lifts – with centuries of science and archaeology behind us – we are exposing a deeper architecture of deception, more thorough than even the early heretics or reformers ever imagined. Beneath the surface layer of biblical invention lies an older theft: the theft of the serpent, the measure, the field, the goddess – the entire symbolic structure of sacred origin.

This is the lie they could never fully erase – only obscure.

And it is this lie we now reveal – word by word, root by root, symbol by symbol.

So, Who Are the Real Scholars?

Is it the gatekeepers of consensus – the curators of inherited dogma – who claim authority by citation and reduction? The ones who dismiss all pattern as coincidence, and all convergence as error? Who explain away a hundred structural alignments as ‘unrelated’ simply because they were not first validated by a journal, inscribed in Latin, or authorised by a member of a self-appointed elite caste?

Or is it those who, like the followers of ‘Pythagoras’, of ‘Imhotep’ – like the builders of Giza, Delphi, Chartres, and Rosslyn – preserved and transmitted the architecture of the sacred cosmos: in sound, in stone, in measure, in myth? Who understood not only the function of number, but the life behind it – the soul and spirit within ratio?

Let us be clear.

Consensus relies on the very men it now fails to embrace.

The initiates – not the academicians – were the true philosophers.

The geometers of light – not the editors of etymology – were the real scientists.

The keepers of the veil – not the gatekeepers of consensus – were the bearers of truth.

When science becomes dominated by gatekeepers, it ceases to be inquiry and becomes doctrine. It becomes scientism – a belief system that defends institutional authority rather than seeking structural truth.

Not all adherents of this cult of scientism are aware of their role in it. Most are not. But some are – those who serve powers greater than themselves, who operate near or within the apex of the symbolic pyramid, aligned with long-standing orders embedded in religion, commerce, and academia.

This, inevitably, opens the ground for what is commonly called conspiracy theory – and rightly so. For when has history not been shaped by conspiracies? By quiet alignments, hidden agendas, concealed knowledge, and deliberate narrative control?

What distinguishes theory from insight is structure, correspondence, and recursion. And those who shaped the foundational architecture of the modern world did not think in material isolation – they thought in symbols, archetypes, and alignments. So do we.

Whether our interpretation is ultimately correct remains open to question. But what we offer is a reasoned belief – that this work presents the most coherent and structurally justified reading of the evidence available. That the cumulative pattern, the symbolic continuity, and the cross-disciplinary correspondence are sufficient to support this as the most accurate conclusion.

The ancients knew what Pythagoras meant – because they lived it.

They are not here to tell us directly.

So it falls to us to recover their meaning – from what they left behind.

Either Or?

The consensus academics will say it is either my speculative version or the correct, established one.

But let us pause – and look more closely.

What is this ‘or’, this disjunction, this gate through which they divide?

In Greek, the word or is rendered as the disjunctive particle ἤ (í), or the conjunctive form εἴτε...εἴτε (eíte...eíte) – ‘either...or’. It is a device of division. A forked road. A split.

But this ‘or’ – this disjunction – is itself a symbol, hidden in plain sight.

For in Egyptian, OR is not a particle. It is a principle.

OR = UR = the origin.

OR is the circle.

OR is the source of light – of Ra, of fire.

And critically – OR is the Veil.

In symbolic typology, OR is the being behind the veil of Isis. The Greek disjunctive ἤ resembles the glyph for the folded cloth – the sign of concealment. The alternative presented by academia – ‘either...or’ – is not neutral. It is the curtain before the origin. The shade before the lamp. The veil before the goddess.

That which is hidden behind ‘either...or’ is not always uncertainty. It is often truth, wrapped.

Through the lens of archetype and typology, etymology and logic, we restore the symbolic truth behind the name:

Pythagoras = The one who moves through serpent wisdom toward the origin of light.

It is the path of the Tetractys, the Phi spiral, the Djed, the omphalos, and the veiled goddess. It is Egyptian in origin, not Greek. The Greeks preserved it – they did not invent it.

This is not theory. It is memory restored.

We still speak the ancient sacred language. Yet academia has divorced us from it. They have taken the perfect statue of David – the beloved, the harmonic ruler – and smashed it. Then they show us the dust and shards and expect us to reassemble it blind, without memory or root.

They claim that Sumerian is unrelated to Indo-European. That Egyptian is purely Afro-Asiatic. But we say it is both. Just as David is not merely an Italian sculpture – he is a universal archetype. A symbol of truth.

Memory survives in speech. As I have shown throughout this work, English retains ancient phonemic roots that are well-established in both Sumerian and Egyptian.

When a modern architect or mason declares that they have created an arch – and anchored it, stabilised it with a capstone – if someone were to hear them say, ‘I’ve measured and wedged it,’ they might unknowingly be echoing the sacred formulation: ‘I have Medjed and Wejet.’

If someone were to remark on ‘an issue with the lugal system,’ one might naturally assume they were referring to the legal system.

If someone were to say they had ‘made a jar on a Ptah’s wheel,’ they would be clearly understood as meaning a jar on a potter’s wheel.

If someone were to say, ‘I’ve put some wine in a gar,’ we would hear ‘jar’.

If someone were to say, ‘Boy, the sun was hot today – I really felt the Re,’ we would hear ‘rays’.

If someone were to say, ‘I’ve dedicated my life to the krst,’ we would hear ‘Christ’.

These are not outlandish comparisons. The phonemic structure is barely changed in thousands of years.

L. A. Waddell saw through the distortions of reconstructed language and exposed their bias. Gerald Massey understood the symbolic function behind the word. We have taken this further – identifying hydronymic, luminymic, and theanonymic roots across Drift Culture memory and aligning them with recurring mythological and linguistic structure.

What may appear as pure speculation in this chapter is in fact derived from evidence – not always in the form of a linear, documented academic lineage, but through structural typology and phonemic or etymological derivations that I have established throughout this work. Some of it remains tentative, and at times highly speculative, but I aim to provide sufficient context to demonstrate that such proposals are not arbitrary. They are rooted in logic, pattern, and recurrence – not conjecture without cause.

The Suppression of the Sacred Feminine and the Inversion of the Sexual Axis

The traditions inherited from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia placed the feminine not as subordinate, but as central to cosmic regeneration. Isis, Ma’at, Inanna, Danu – these were not merely maternal figures. They were structural principles: the breath of life, the field of form, the matrix through which resurrection becomes possible. The body, in these systems, was not shameful. It was sacred – a living glyph.

In Egyptian theology, the resurrection of Osiris is performed not by any male god, but by Isis. The dried and dismembered corpse – the kar – is reconstituted through the sacred waters of the goddess – the st. The resulting structure – KRST – is not a man, but a symbolic field-body: an axis raised through feminine anointing.

This archetype – later overwritten by Christian theology – was originally a structural metaphor, not a biographical claim.

Likewise, the god Min stands in full erection, arm raised, crowned with cobra iconography, and holding the flail – a symbol of generative control. He is the living Djed. His phallus is neither hidden nor shamed; it is the visible axis of creation. The pointer, the measure, the source of life. The Egyptians, as the keenest observers of nature, recognised the penis as the origin of all human and most animal life. It was therefore naturally sacred.

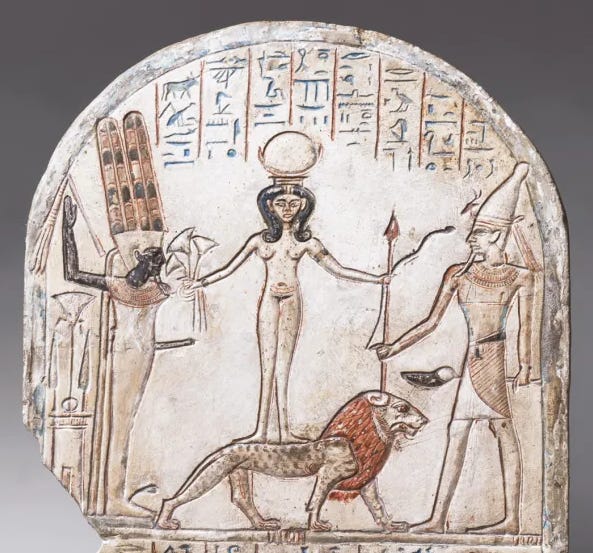

A stela from Deir el-Medina, depicting the Syrian goddess Qadesh, who became the consort of Min during the Eighteenth Dynasty. Image: Museo Egizio, Turin - from article Min: the most popular deity in the Eastern Desert?

But this organic structure was later inverted.

As the Roman imperial system absorbed and restructured the mythic codes, it rendered sacred symbols profane, and redefined the generative body as sinful. The phallus, once a symbol of measure and breath, became an object of shame. The vagina, once the sacred gate of emergence, was concealed – even as its form was replicated in cathedrals, mitres, and ecclesiastical architecture.

Sacred sexuality – once understood as the convergence of polarity through Ma’at – was reduced to sin, guilt, and control. The field-body of resurrection was replaced with a crucified male. The balance of feminine and masculine was rewritten as a hierarchy. The spiral became a cage.

And thus the axis – once a path of breath and regeneration – became the cross of oppression.

Unleavened Bread and the Removal of Breath

In the Hebrew tradition, and later in Christian sacramental practice, unleavened bread became the prescribed standard. Yet in Egyptian symbolic logic, bread that rises does so by breath – fermentation, expansion, animation – all attributes of Hu, the divine utterance of Atum, and the life-bestowing principle of the goddess. Leavened bread was a living glyph: it rose, it expanded, it took in air – and in so doing, became an edible expression of life-force. Bread and beer were sacred to the initiates for this reason.

By contrast, unleavened bread is lifeless. Dry. Flat. Breathless. Its ritual imposition – especially in sacred observances such as Passover and the Eucharist – marks the removal of the feminine, the denial of breath, and the rejection of living matter as holy. It is rendered merely functional: to fill the belly, not to embody spirit.

In Christian liturgy, the host – flat, pale, and sterile – becomes the emblem of a body without breath, offered in the name of resurrection while stripped of the very processes that give rise to life.

The Rising Phallus and the Sacred Axis

Naturally, life issues from the penis only after it has risen – when it is filled with, and expresses, the ‘male milk’ of semen. No examination of the archetype of rising – whether in the Djed, the Benben, or any related symbol – can be complete without addressing the phallus.

Any treatment of the axis mundi must therefore include sacred erotic symbolism, as expressed overtly in the Egyptian tradition. One of the most striking depictions is Geb lying on his back, with the naked goddess Nut arched over him – the earth below, the sky above, body and field in unbroken contact. In this scene, Geb declares: ‘As Geb, I shall impregnate you in your name of Sky.’

Here, the axis is not a metaphor. It is embodiment. The vertical is not abstract – it is literal, generative, and therefore sacred. Nothing is truly divine if it is abstract and unreal – if it exists only as theological decree, without grounding in nature.

Circumcision and the Decapitation of the Serpent

The phallus, once sacred, was anatomically altered. In Egyptian cosmology, the uncircumcised penis – especially in erection – mirrors the hooded cobra, the uraeus, sacred to Wadjet, who protects the brow and enables divine insight. The foreskin is symbolic of the serpent’s hood: it flares, it guards, it conceals. In this context, the serpent is not shameful, but sacred – a sign of awakened vision and generative wisdom.

The ritual removal of the foreskin – circumcision – constitutes, symbolically, a decapitation of the serpent. It is the removal of the hood, the severing of the field-laden crown from the axis. In Judaic law, this act is defined as covenant. In Christian contexts, it is inherited theologically or preserved through cultural custom, yet the ritual is reversed in doctrine – reframed as a rejection of Judaic legalism. (Later, I will explore how this reversal served not a theological, but a political function.)

In either case, the result is the same: the phallus is stripped of its original serpentine resonance. What remains is a hoodless stalk – neutralised. No longer symbolic of wisdom or protection, god or Ned, but of legal submission.

Ecclesiastical Dress and the Inversion of Sacred Anatomy

The serpent and phallus were not only stripped of symbolism – they were re-encoded through priestly attire and gesture. Yet the forms persist:

The monk’s hood is symbolic of a collapsed cobra hood – a covering once sacred, now worn as submission.

The tonsure – the shaving of the crown – reproduces the garlanded head of the phallus, echoing the meatus, but shorn of potency. Said to represent the crown of thorns, but more likely a sign of submission to Roman imperial theology – a mimicry of the laurel wreath of the Emperor.

The mitre is a stylised phallus. Its vertical split mirrors the cleft of the glans – the meatus. Shaped like the open mouth of a fish or the beak of a dolphin, it reflects earlier aquatic symbolism: life-bearing semen, the waters of the field, the breath of the goddess. The dolphin, sacred to Apollo and the Delphic Oracle, was a classical emblem of rebirth. The early Roman-Christian iconography of anchor and dolphin encodes this logic: the anchor as phallus or Djed, the dolphin as semen or spiral generative force. These forms were preserved – but their meanings inverted or denied.

And yet, even as the mitre is worn as a symbol of male authority, its cleft implies the goddess. The feminine is always present – never named, but never absent. This is the method of veiling: to retain form, while denying function.

One of the central disputes at the Synod of Whitby in 664 CE concerned the correct form of the tonsure – the ritual shaving of clerical hair. The Roman (Petrine) tonsure, which involved shaving the crown and leaving a ring of hair, was eventually imposed across Britain. The form of the Celtic tonsure, however, remains debated. Some accounts suggest it involved shaving the head from ear to ear, leaving the crown untouched – a form which would symbolically preserve the serpent hood or wedjet crown atop the skull.

If the Celtic tonsure did retain the function of the sacred crown, then this dispute was far more than a disagreement over hairstyles. It was a confrontation over spiritual authority, initiation symbolism, and cosmic alignment. In that context, the Roman imposition of a new tonsure was not merely disciplinary – it was a ritual severing of the axis. A symbolic rejection of the connection between the head, the serpent, and the breath of wisdom.

For the Celtic monastics – likely steeped in esoteric memory and sacred geometry – the adoption of the Roman tonsure would have been intolerable. That they withdrew to Ireland following the Synod is often dismissed as cultural stubbornness. But it is more credibly understood as a refusal to submit to the inversion of sacred structure by an invading power.

The plain fact of biology shows that the vagina is an entrance crowned by a protruding clitoris, itself cowled by a hood of skin. In contrast, the penis is a protrusion ending in a small exit at the meatus, likewise cowled. This is a direct expression of recursive duality in nature – ingress and egress, enclosure and projection – and it is precisely the kind of structural polarity the Egyptians observed, honoured, and symbolised in their theology.

The commonality lies not in function or dimension, but in form – and above all in the hood, which echoes the Wedjet serpent, the cobra, the emblem of protection, insight, and veiled power. Even in English, the sacred sound is retained – the ‘hoo’ of Hu in hood. Just as the hydronym car is retained in cowl.

Here again, in the symbolism of the generative organs, the feminine archetype dominates: the clitoris is not absent, but veiled; not subordinate, but crowned. In both anatomical structures, the presence of the cowl or hood points back to the Isis archetype – the goddess as she who is veiled, the one who guards the axis, conceals the mystery, and reveals only to those who seek with purified intent.

The Church as Recast Body: Architectural Eroticism Without Acknowledgement

Ecclesiastical architecture retains many of the visual cues of the sacred feminine - yet these are never acknowledged, only sublimated.

The church doorway is vaginal in shape - a vertical arch.

The rose window or rose shaped capstone in the arch, at the apex represents the clitoris or the crown of spiritual illumination, set precisely where the energy would rise. The wedge of Wedjet in place to support the structure.

The nave becomes the vaginal canal, leading to the altar.

The dome overhead echoes the womb - the enclosure of heaven, as well as the medjed or benben form.

These are not incidental. They are the residues of earlier symbolic structures. But where once these forms invited entry, union, and breath, they are now sites that barely remember their origins. The body is there, but denied. The erotic is present, but criminalised. The goddess is implied, but never spoken.

Celibacy and the Total Prohibition of the Feminine Body

Celibacy was introduced not merely as discipline, but as doctrine. The body was recast as temptation. Flesh became the enemy.

Sexual activity was forbidden.

Masturbation became a moral crime.

Nakedness, even implied, was subject to regulation.

Female flesh, in particular, was covered, controlled, or condemned.

Even the word twat – clearly derived from Tuat or Duat, the Egyptian underworld and womb-space of rebirth – was degraded. What had once been a gateway of stars became a vulgarity. The vagina, once the temple entry, became the site of shame.

All of this was ultimately blamed on Eve – the one who disobeyed the Lord and listened to the serpent. She, and all womankind, were burdened with this original dishonour – the stain of Original Sin. From that point, nakedness was shameful. To see female flesh – or even think of it – was considered sinful. The feminine body became taboo.

But who, truly, was the first sinner in the Bible? The one who disobeyed the Lord? Or the one who disobeyed the liar?

One of God's first acts in Genesis was to prohibit Eve from obeying the serpent – who promised knowledge. The serpent was ultimately correct. Eve did not die as God had said. She gained knowledge, exactly as the serpent had promised. It was for that – the acquisition of knowledge – that she was punished.

God had declared that on the day she ate the fruit, she would die. But she did not die.

Much theological effort has been spent trying to resolve this. The standard defence claims that Eve introduced mortality, and that God did not lie – only that his words were misunderstood. A convenient interpretation – and one that conveniently lets God off the hook as the first liar in the Bible. It also serves those who insist the Bible is the literal Word of God – except, of course, when they themselves choose to interpret it figuratively.

We have already established that Adam and Eve are none other than Atum and Iusaas.

Atum, whose penis created the first form through his ejaculate.

He ‘came’ – and was ‘iusa’, the ever-coming one – not only in the sense of eternal recurrence, but as the generative creator through male ejaculation.

Atum’s penis became Adam’s rib – through ambiguity and mistranslation. The ribcage is where the female milk-giving orifices lie. The penis is where male ‘milk’ – semen – emerges. The symbolism is obvious when viewed through Egyptian logic.

The Bible, by contrast, is a much later, politicised construction – one that distorts nature’s truths for the purpose of social control.

That the serpent – once the bringer of insight – became the deceiver, and Eve the disobedient fool, while it was actually God who was deceptive, is typical of the Bible’s inversion of myth, archetype, and symbolic truth. The feminine was rebranded as error. The masculine god was recast as the sole authority. All wisdom – once embodied in the serpent, the goddess, and the erotic axis – was stripped, inverted, and encoded as sin.

Such inversion lies at the heart of religious power.

And at the root of its fear – is always the body of the woman.

Osiris, the Lost Phallus, and the Cosmic Axis

In the myth of Osiris, Isis, and Set, we find one of the most enduring cosmological motifs: the dismemberment of the divine body and the loss of the generative organ.

When Set murders Osiris, he cuts his body into pieces and scatters them across Egypt. Isis, in her role as restorer and reassembler, gathers the fragments, reconstructs her husband’s form, and through sacred breath and magical rite, reanimates him.

Yet one part is missing: the phallus – the generative axis – which, according to the myth, was swallowed by a fish. Isis fashions a new phallus herself, often said to be made of gold or wax – a constructed Djed. And through union with this reconstituted axis, she conceives Horus.

This narrative is not merely mythological. It is overtly sexual. It encodes a foundational principle of Egyptian cosmology:

The resurrection of the axis requires the feminine.

When the natural phallus is lost, it is not replaced by divine fiat or sacrifice – but by the hand of the goddess. She restores it, refashions it, and reanimates it. The body does not rise by martyrdom, but by breath, by joining, by alignment with the field.

Minos and the Bull: Greek Echoes of Egyptian Archetypes

The later Greek myth of Minos and the Minotaur reflects a distorted memory of the Egyptian cosmological structure.

Minos, whose name may derive not from a personal name but from a title based on the Egyptian god Min, is associated with judgment and the labyrinth – a symbolic echo of the Duat or underworld passage.

The bull, which becomes the Minotaur, represents an uncontrolled phallic force, imprisoned within the labyrinth – an axis severed from the feminine, now monstrous.

Pasiphaë, who unites with the bull, is a veiled echo of Isis – a goddess-figure whose union is recast as abomination rather than sacred joining.

The labyrinth itself is a geometric distortion of the womb-temple – no longer a place of initiation and return, but a trap, a maze, a site of fear and forgetting.

In this inversion, the bull – once a glyph of strength and generative power (as in Apis or Taurus) – becomes dangerous. The union with the goddess is prohibited. The labyrinth is no longer a cosmic path. It is a prison. The phallus is no longer celestial. It is buried beneath shame and secrecy.

Yet in the sky, the truth remains: Osiris, as Sah of Orion, forever faces the bull Taurus in our prime stellar nexus. His masculine force – generative, initiatic – is required to meet the power of the bull. And always, just behind him, rises his consort: Isis as Sothis – Sirius – the feminine field, the breath of return.

In the oldest Egyptian cosmology, it is Atum who generates creation through masturbation – not as an act of shame, but of cosmic potency. He brings forth Shu and Tefnut from himself, often shown doing so by his own hand. But this hand is not merely anatomical. It is symbolic. It is the goddess-consort, the feminine force that enables and directs the act.

The generative impulse is male – but the hand that brings it forth is female.

The axis initiates. The field receives, shapes, and aligns.

Creation is not an act of isolated power. It is always an act of polarity – even when expressed through a single form. The goddess is always present – even if veiled as gesture, as breath, or as a hand.

Etymology and Symbolic Morphology

Here I extend the natural symbolism drawn from evidence – because none of this would escape the notice of an initiate who thinks in archetypes and correspondences, as we do. What follows may strain academic credibility in the conventional sense, but we must ask: when have we ever bowed to academic consensus if the typology remains accurate – linguistically, etymologically, and mythically?

The symbolic logic holds. The structures are consistent. And for those with eyes to see, the deeper continuity between body, language, and field is unavoidable.

Monk

From Greek μοναχός (monakhós) = ‘solitary one,’ from μόνος (monos) = ‘alone’

Proto-Indo-European root men- = ‘small, isolated, apart’

This root gives us monos (alone), monad (indivisible), monarch, and monk

Thus: monk = the one who stands alone – the isolated axis.

Symbolically: the Priapus-type – the solo phallus, set apart from the field.

Priapus, the Greek fertility god, erect and alone, arose from the primordium – just as Atum arose from the primeval mound of Ptah.

Monastery

From Greek monastērion = ‘place of solitude’, from monazein = ‘to be alone’

Built from the same mono- root

Yet in reality, monasteries are not solitary. They are communities – cells of celibacy, organised around a ritualised denial of union.

Ministry

From Latin ministerium = ‘service, attendance, office of a servant,’ from minister = ‘inferior, servant’

Rooted in minus = ‘less’ – denoting subordination, but also smallness, humility

Yet within Christian structure, ministry becomes authority – a theological paradox: the one who serves becomes the one who rules.

The minister is Priapus with licence – the male axis in ritual service to the divine, but without union.

The Hidden Polarity: Min + Esther / Ishtar

Now we introduce the symbolic pairing of Min and Esther – an encoded polarity:

Min is the erect, generative god of Egypt – the standing Djed, the axis. He is the clear precursor to Priapus.

Esther represents feminine field resonance.

Ishtar, Astarte, Ashtoreth, and Esther are all linguistically and morphologically descended from ancient goddess traditions.

These names carry resonance with womb, star, field, mother, and fertility.

Esther is a veiled name, preserved in scripture but stripped of divine status. Her cousin, Mordechai, is a direct linguistic link to Marduk.

Thus: Min–Esther symbolises Min within Esther – the male axis (Min) placed within the feminine field (Esther/Ishtar/Eostre). She is encoded, but veiled – embedded within the structural function of ministry.

Perhaps the link denied by consensus academia – between ministry and Min, the solitary generative phallus – is most clearly preserved in the term minster. Consider York Minster and Westminster Abbey. Both are regional ad-ministra-tive axes of ecclesiastical power – crowned with vast towers and pointed spires.

These are not simply architectural flourishes. They are glyphs of the Djed – towering generative forms.

Min–ster is almost exactly Min’s star – and as shown, star shares root structure with Esther, Ishtar, and Isis.

Either that, or this is all another coincidence.

To state the case clearly: if one traces a word only partway back through its recorded lineage, and ignores earlier bifurcations of meaning or form, then consensus etymology can declare a truth to be false.

Language is not always linear. It drifts. It forks. It collapses. It is redirected by culture, by power, by secrecy. Etymological declarations made without reference to symbolic continuity, initiatory transmission, or historical redaction risk mistaking absence of evidence for evidence of absence.

In this case, ministry and minster are denied as related – yet conventional etymology only traces both back as far as Latin and Old English.

This is where we are ahead of the game: recognising the typological continuum and the deeper etymological roots.

I have developed what may be the most advanced symbolic pattern analysis system currently available – a multilevel AI-assisted framework called VENIX. It is a simple but powerful tool, designed to eliminate bias, bypass shallow linguistic tracing, and focus on known data structures.

By examining cross-cultural symbols, linguistic recursion, and functional continuity, VENIX compiles a numeric value representing the truth-likelihood ratio (TLR) of any given claim, based on multi-tier meta-analysis.

When applied to the AI-generated assertion that minister and minster do not share an etymological relationship, VENIX returned a TLR score of 0.42 – indicating low reliability.

My own model, by contrast, scored the relationship at 0.83 – indicating strong structural continuity, even if not formally acknowledged in classical etymology.

This reflects not speculation – but a more complete reading of the symbolic and functional systems that shaped our languages and institutions.

The Veiled Hieros Gamos

This may appear to stretch credulity, but becomes increasingly pertinent as we see Min 'pop up' again later in Vedic myth and symbolism. With words that appear related to Min, such as men, we also find the feminine counter-term menses. One is obviously masculine, the other clearly feminine. Do they share a common mythic root? As we have seen, god and goddess are always related in ancient dualistic symbolism whenever it involves creation. These words are often theanonyms, with a shared mythic structure in the background. It is not unreasonable, then, to contemplate that the masculine and feminine separated in language just as they separated in myth.

Menses is not an isolated term. It shares phonetic and etymological roots with moon, mind, mania, and month. All derive from the Indo-European root men- or mēn-, which consensus etymology traces to the concept of measure - particularly time. But for early societies, time was not measured by clocks, but by the moon. The lunar cycle governed planting, tides, and most crucially, the female body. Hence, menses is literally the measurement of the feminine cycle in moonlight.

From mēn- we also derive moon, the celestial regulator of feminine rhythm; menses, the visible outward sign of that rhythm; mind, the container of thought and reflection; and mania, the disruption of mental order. The implication embedded in this sequence is that the feminine rhythm, being lunar, is unstable - waxing and waning, bleeding and retreating in flux. The mind, when unbound, becomes manic. The female becomes moonstruck. Hence also lunacy, from luna, the moon - long associated with female ‘madness’ or disorder.

In contrast stands Min - the archetype of stability. The phallus is erect. The god stands upright. He is the guardian of form, constancy, and directed generative force. He is still while the world turns.

Linguistically, Min is compact, fixed. Its sound does not flow or spiral - it states, it stands, it anchors.

This dualism is repeated across mythological systems worldwide: order and chaos, male and female, sun and moon, axis and field. One projects, the other surrounds. But under patriarchal reorganisation, the sacred matrix of the feminine was reframed as disorder. Her cycles became signs of danger. Her blood became a curse. The moon became madness. The womb became pathology.

Menses, once a synchronised sign of divine rhythm, was reframed as a marker of impurity. The very word that once indicated her sacred timing was rebranded as a symbol of shame.

Meanwhile, the masculine axis - Min - retained his position as upright clarity, control, and stable reason. Even when rendered absurdly or mythically, the male generative symbol was never mocked. It was glorified.

This resulted in a structural manipulation: the feminine was essential yet marginalised; her bodily functions coded as dangerous; her generative role pathologized. The male was cast as free from tides, blood, or madness - as stable and sane by default. The language itself came to preserve the drift: the repression of sacred polarity through etymological inversion.

To realign this system is not to play games with language, but to recover what was embedded in it - that words like menses, moon, and mind are not signs of disorder, but of sacred rhythm. Only when we see the flux as heartbeat rather than chaos does the goddess return to her rightful role as co-creator. Her blood is not danger. It is the signal of becoming.

It is even tempting to see the word Amen - the ritualised ‘so be it’ - as a Roman pun: a-menses, ‘no menstruation here’. No goddess. No feminine flow in this book. Again, this may seem a stretch, but as will become increasingly clear, Roman puns are among their most deliberate and revealing devices. They did not deny the goddess directly. They veiled her - in word, in law, in ritual.

Feminine archetypes were routinely re-coded with negative connotation. The term venereal comes directly from Venus - the Roman goddess of beauty, love, fertility, and sacred sexuality. Yet it is now associated with disease - with sexually transmitted infection. The name that once signified generative love becomes a symbol of promiscuity, contamination, and fear. Likewise the pentagram - the star of Venus, drawn from Phi - became demonised as a satanic mark. The act once blessed by Venus became immoral. The vessel of life became the risk.

So too with hysteria - derived from hystera, Greek for womb. Until the twentieth century it was used as a formal diagnosis for supposed feminine irrationality. A label applied to nearly any behaviour deemed inconvenient, disruptive, or independent. The womb, rather than being honoured as the creative core of all life, was cast as a source of instability - a site of madness and moral danger.

These shifts did not emerge by accident. They represent a consistent cultural programme: the disempowerment of the goddess and the inversion of her bodily powers into pathologies. Venus, Isis, Inanna, Hathor - all goddesses of love, beauty, fertility - are rewritten as harlots, sirens, or madwomen. Their symbolic gifts - menstruation, conception, sexual pleasure, childbirth - are covered in shame, medicalised, legislated, and distorted in language itself.

To reverse this requires more than reinterpreting ancient myth. It requires restoring the feminine in language - in naming, in rhythm, in cycle, in breath. When Venus means love again, and not infection; when the womb is seen as wisdom, not disorder; when menstrual blood is no longer taboo but seen as life’s signature - then the words themselves can once again function as glyphs of truth, not fragments of distortion.

Until then, language remains as archaeological evidence - a record of what was suppressed, and what now must be restored.

In the original mythic structure:

The union of Min and Esther/Isis/Ishtar = the hieros gamos – the sacred sexual union

The KRST is the result of this joining: the anointed form

In Christian liturgy:

The minister performs communion – symbolically a joining: body and blood, spirit and matter

Yet the female principle is absent

There is no Isis, only a male celebrant and a genderless wafer

The host (from hostia = victim) is unleavened – no breath, no field, no fertility

The body enters the church, the phallus enters the temple, but the womb is absent. The goddess is veiled – always implied but never invoked.

And yet, sexual union is what creates the entire human race. A penis enters a vagina to create a child. The Son comes always from Mother and Father – in the symbolic myth and in natural reality. To deny this is to deny Nature itself. And this is precisely what biblical theology tends toward – a fantasy and denial of Nature, replaced by a man-made structure that imposes its will upon the world by redefining Creation according to its own needs, not its observed reality. It constructs a symbolic order in which man is sole actor and sole authority, and where the field, the womb, and the feminine are overwritten or removed.

But Nature does not lie. Creation comes through union. And all doctrine that denies this is a denial of life.

This produces a reversed ritual structure:

The monk is the isolated phallus, celibate, standing alone

The monastery is the contained womb, but barren – no union permitted

The minister enacts the joining (communion), but with no feminine partner

Even the word communion – from Latin communio = sharing, union – is transformed:

From a sexual-spiritual convergence into a ritualised consumption of a dead male body

The act of joining is simulated without the presence of the feminine principle

Synthesis: The Axis in the Field, Veiled and Reversed

In origin:

Min stands in the field of Esther, Ishtar, or Isis

The phallus is raised, the goddess anoints, the Djed is restored

The vagina is moistened, thereby lubricating the passage for the penis

The sacred union produces life, measure, and resonant form

In Christian liturgical inversion:

The phallus is denied

The goddess is veiled or banished

The field becomes cloth

The anointed becomes Christ, stripped of Isis

The ritual becomes a mimicry, where only the axis is named and the field is implied

There is no water, no lubrication, no anointment – except by lip service to the myth

This is the ministry – Min without Esther, Ishtar, or Isis

The monastery – the axis within a wombless temple

The monk – the phallus without the serpent

The communion – the union without the goddess

An asexual act, ethereally performed by a community of men.

Whereas in the nunnery, the same logic applies in reverse - an asexual union symbolically performed with the male god, resulting in no offspring, and perpetuating the concept of the feminine as servant of the male. She becomes a Bride of Christ - a partner to a distorted myth, with no hope of natural consummation. Expected to remain dry between the legs, as it will never be used for its ‘God-given’ function.

The Men of the Cloth

The culmination of this systemic inversion is the figure of the priest - the ‘man of the cloth.’ The phrase itself reveals the trajectory:

The cloth, once the sacred veil of Isis, becomes the instrument of concealment.

The axis, once anointed, becomes forbidden.

The phallus, once sacred, is denied.

The goddess, once the central animating force, is rendered either virgin or whore - or erased.

Thus those who once stood at the convergence of field and form became the custodians of denial.

By the time the Roman authorities had compiled and canonised their Bible, they had already demonstrated themselves to be unparalleled masters of manipulation, double standards, and symbolic inversion. While presenting themselves as civilisers and spiritual authorities, their governing ethos was structurally aligned with the very vices they would later codify as the Seven Deadly Sins. It was these sins far more than their seven hills that appear to be their foundational typology and character traits. These so-called capital vices, drawn from early Christian teachings and systematised by later theologians, form a moral framework that Rome demanded of its subjects - all while embodying the very vices they condemned.

Pride – excessive belief in one's own supremacy

→ Everything was for the glory of Rome; all triumphs, all territories, all gods were ultimately absorbed into the imperial image of dominion.Greed (Avarice) – obsessive pursuit of wealth and dominance

→ The Roman Empire existed to extract wealth from indigenous populations, funnelling gold, land, and labour back to the imperial centre.Wrath – vengeful domination and violent reprisal

→ The God of the Old Testament - whom they adopted as their own - was cast in their image: jealous, punitive, and destructive.Envy – covetous appropriation of other cultures

→ Rome annexed temples, rituals, names, and gods - from Egypt to Britain - remaking them as Roman property by imperial decree.Lust – culturally institutionalised excess

→ Despite moralising scripture, Roman society was renowned for sexual indulgence, ritualised orgies, and the state-sanctioned celebration of excess.Gluttony – excess in consumption and opulence

→ The elite practised overindulgence as ritual - with banquet halls, vomitoria, and endless display of luxury as status.Sloth – moral indifference and religious hypocrisy

→ While preaching moral restraint, Roman authorities turned a blind eye to their own corruption, violence, and decadence - a refusal to live by the values imposed on others.

Contrast this with the Seven Heavenly Virtues (as demanded of the flock):

Humility – self-denial and obedience

Charity – redistribution (encouraged among the poor, not the rich)

Patience – tolerance of injustice, even under occupation

Kindness – submission in the face of cruelty

Chastity – repression of natural desire

Temperance – acceptance of one’s station

Diligence – productive labour in service of the Church and State

These virtues were presented as divine ideals - and encoded into scripture. The masses were taught that humility was holy, that suffering was sanctified, and that submission was godly. ‘Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s,’ they were told. ‘Turn the other cheek.’ Obedience was now spiritual. Resistance was now sin. Disobedience was now immorality.

The Mechanism of Control: Carrot and Stick

Rome enforced its system through a dual mechanism: incentive and coercion - the promise of reward, and the threat of punishment.

Where religious integration succeeded, Roman rule was spiritualised through temples, festivals, and the absorption of local myth.

Where it failed, brute force followed - crucifixions, burnings, decimations, and the destruction of indigenous priesthoods (as in Judea, Gaul, Britannia, and Carthage).

Over time, the flock learned: submission meant safety; obedience brought grace.

Thus was the empire spiritualised. The shepherds of the so-called faith - bishops, priests, and theologians - became the enforcers of empire. The shepherds of Rome - city of the wolf-mother - turned sheepfolds into fortresses. And as every initiate and farmer knows: when the wolf meets the sheep, it is not the wolf who bleeds.

This contrast is not incidental. It reveals a systemic moral contradiction: those who preached virtue to the masses were structurally aligned with the very vices they condemned. The Roman institution, cloaked in religious authority, presented itself as the arbiter of virtue while exercising power through its systematic inversion.

Romans 13: The Manifesto of Imperial Control

I reject the theological and academic debate that seeks to frame the following Pauline passage as nuanced spiritual doctrine, or a veiled attempt to spread the Word while avoiding the wrath of Rome. I do not accept the many interpretations which claim the text is taken out of context, or that it requires layered exegesis to be properly understood. It is what it plainly appears to be: a written rationale for political subjugation, authored by and for the Roman elite.

Qui bono? Who benefits? Rome.

Who authorised it as part of their canonical text to support their fictitious history of Jesus? Rome.

Who then presented it to the flock as canonical instruction? Rome.

No matter who or what Paul was – whether the writing is an authentic letter or not (though possibly a Roman fake, after the style of Eusebius) – none of that really matters here. The simple fact remains: Rome put it in their book and used it to control the masses, to tame them, and to deceive them into believing fiction as history. They clearly intended it to be exactly what it appears to be – direct instruction to obey the Romans, or else.

Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God.

Consequently, whoever rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and those who do so will bring judgment on themselves.

For rulers hold no terror for those who do right, but for those who do wrong. Do you want to be free from fear of the one in authority? Then do what is right and you will be commended.

For the one in authority is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for rulers do not bear the sword for no reason. They are God’s servants, agents of wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer. (my emphasis)

Therefore, it is necessary to submit to the authorities, not only because of possible punishment but also as a matter of conscience.

This is also why you pay taxes, for the authorities are God’s servants, who give their full time to governing.

Give to everyone what you owe them: If you owe taxes, pay taxes; if revenue, then revenue; if respect, then respect; if honour, then honour. – Romans 13:1–7

This is not wisdom. This is not ethics. It is a manifesto for submission, cloaked in theological language to grant imperial governance the aura of divine legitimacy. This is not spiritual truth – it is a blueprint for obedience. Written not by prophets of moral enlightenment, but by men embedded in – or serving – the Roman system of domination.

That this passage appears in the Bible – a text which elsewhere teaches true virtue: compassion, forgiveness, the dignity of others, the golden rule – is precisely why it must be recognised as a contradiction. Yes, the Bible encodes great wisdom, drawn from Egypt, Greece, and the philosophical lineages of antiquity. Yes, many Christians live by the highest ethical standards encoded in that wisdom. But this passage is not part of that legacy.

This is where morality was weaponised.

Romans is the moment where righteousness was rewritten to serve Rome. It is the juncture where law was deified, and the sword made sacred. It declares that taxation is holy, that obedience is moral, that rulers are agents of God, and that resistance is a crime not only against man, but against heaven.

This is the voice of empire – not of God.

And it was the priests and clergy – appointed not from spiritual ecstasy, but by ecclesiastical authority – who became the foot-soldiers of this system. These were the enforcers of divine hierarchy, earthly taxation, and moral silence.

History has proved repeatedly that when an authority employs enticement and coercion to instil a sense of good and bad within a population, a clear, stark division develops that is ripe for exploitation. This method is so simple and so effective that it continues to be employed by Machiavellian elites to this day.

It has been evidenced countless times throughout history: those professing to worship the Prince of Peace and his God have tortured and slaughtered the ‘other’ out of a conviction that they were ‘good’ – and that the targets of their violence were ‘bad’, because authorities told them so.

A recent example occurred during the Covid pandemic. A programme of ‘persuasion’ was deployed to convince the public that those who obeyed the rules were good, and those who questioned them were bad. Governments used both enticements and coercions that had long been outlawed under the Nuremberg Code. Medical decisions are, by that standard, supposed to be based on fully informed consent – free from both pressure and reward. Enticement and coercion are forbidden.

Yet they did so.

Entire societies became divided. Some called for the dissenters to be locked up, punished, or denied treatment – convinced they were morally righteous because they had obeyed the message of authority. They believed themselves to be on the side of ‘good’, even though those same authorities later admitted to using illegal coercion, unlawful enticement, and deliberate psychological pressure.

A campaign of exaggerated fear and state-sponsored misinformation was openly confessed after the fact – all deployed to ensure uptake of a new, rushed-to-market vaccine, developed on a genetic therapy-based platform that had never previously been used in mass human application. A vaccine with a history of flawed and manipulated trial data, and potentially lethal consequences – promoted in direct violation of the Nuremberg Code, which was specifically established to prevent such abuse of medical authority ever again.

The slogan ‘safe and effective’ was never proven – yet the majority accepted it without question.

One of the architects of this global response – Jesuit-educated Anthony Fauci, Director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases – echoed the doctrine of Romans 13 almost word for word when he declared:

“Attacks on me, quite frankly, are attacks on Science.”

He may as well have quoted the scripture directly: “Whoever rebels against the authority is rebelling against what God has instituted.”

Sex as the evolutionary driver

Anthropology has long explored the question of how Homo sapiens became the dominant human species, but the deeper motivational drivers behind this ascendancy remain largely underexplored. One such neglected factor is the human sex drive itself. When viewed not merely as a reproductive instinct but as a total behavioural force, the hormonal and erotic impulse offers a powerful lens through which to reinterpret the emergence, expansion, and supremacy of Homo sapiens over other hominin types such as the Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Homo sapiens appears to have possessed a heightened hormonal profile that encouraged exploratory behaviour, novelty seeking, and reproductive assertiveness. Elevated testosterone levels in males are strongly correlated with risk-taking, movement, and conquest of new environments. This is not merely incidental. The act of moving on from overpopulated or resource-stressed areas may have served, in part, as an expression of the alpha drive - a hormonal urge to find new opportunities for status, reproduction, and adventure. Although Neanderthals appear to have matured more rapidly in physiological terms, they did not reproduce at the same rate, and likely lacked the same expansionist drive.

The hormonal structure of Homo sapiens also supports more complex bonding mechanisms. Oxytocin, the hormone associated with social bonding and trust, likely played a larger role in the formation of extended kinship networks, which allowed for greater integration between disparate groups. This would have allowed not only for more frequent sexual encounters across tribal boundaries but for the consolidation of cultural and genetic traits into a wider, more resilient species profile.

Interbreeding provides one of the strongest pieces of evidence in support of this theory. Virtually all modern non-African humans carry between one and four percent Neanderthal DNA, and many populations also exhibit Denisovan genetic markers. This suggests not isolated contact, but rather ongoing sexual interaction across generations. The interbreeding pattern is largely asymmetrical - with Homo sapiens males breeding with Neanderthal or Denisovan females, rather than the reverse. This asymmetry suggests an assertive - perhaps dominant - reproductive behaviour by Homo sapiens males during periods of migration and encounter.

Population dynamics also play a significant role in this picture. Archaeological evidence shows that Homo sapiens populations grew rapidly, often resulting in pressures that triggered further migrations. Neanderthals, by contrast, appear to have remained in smaller, more stable bands with lower overall reproductive rates. Their populations did not overpopulate or expand in the same way, and there is little evidence of symbolic mating displays or wide-ranging social rituals comparable to those of Homo sapiens. In this light, sexual drive and the social behaviour that emerges from it can be seen not as background noise, but as a central force in demographic expansion.

It is also worth considering that Homo sapiens’ expansionist behaviour was not simply a side effect of environmental necessity, but also a direct expression of hormonal incentive. Novelty seeking, mating opportunity, and the dopamine feedback loop of conquest - sexual, social, and territorial - may have driven early humans to push into new territories long before material need became urgent. This erotic engine, as it might be termed, would have naturally selected for those individuals most willing to take risks and engage with the unknown, thereby spreading their genes more widely than any other human type.

The final result is clear in the genetic record. Homo sapiens did not merely survive contact with other hominin species - they absorbed them. The legacy of that absorption is carried within our very DNA, a testament to the fact that dominance was not won through violence alone, nor through intellect alone, but through an overwhelming reproductive strategy that outpaced, outlasted, and ultimately replaced all rivals.

This dimension of human evolution - rooted in the sex drive, hormonal feedback, and the urge to expand - has been largely overlooked in traditional anthropology. Yet it offers a vital key to understanding not only the triumph of Homo sapiens, but the underlying logic of mythology itself. Where myth speaks in the language of desire, fertility, conquest, and mating, it encodes the deeper biological story of our emergence. The Storm God, whose cultic and symbolic manifestations are explored throughout this work, is not only the bringer of rain and the wielder of thunder.

He is also the embodiment of fecundity and fertility, the driving force that pushed man beyond the edge of the known world - seeking not only land and food, but sex, power, and the ecstasy of expansion.

The Implosion stage of cultural development

If the sex drive accounts for the expansionary thrust of Homo sapiens, then the survival drive accounts for his pattern of settlement, cultural emergence, and symbolic development. At the most fundamental level, man is driven not by abstract ideals but by necessity - the need for water, food, and shelter. The environment dictates the mode of life. He studies nature not to worship it, but to live. Observation becomes the first sacred act, because it is the means by which he learns to survive.

Early man does not leave the riverine zones until he has mastered them. He builds culture only where nature first provides the conditions for life. The fertile crescent is not only the birthplace of agriculture - it is the cradle of myth. It is only after the necessities are secured that the symbolic imagination truly ignites and is amplified. When the belly is full and the body is sheltered, the mind turns to the stars. Creativity is not an excess - it is a pressure release. It is the redirection of instinct, the upward movement of energy that once pulsed through the groin and now flows through the hand, the eye, the voice. It is the flowering of instinct, when no longer needed for survival.

Mesopotamia arises because water is plentiful and predictable, soil is rich, and food is assured. The Tigris and Euphrates permit farming, which permits settlement, which permits time. With time comes rhythm, observation, recollection. These become ritual, myth, and art. The gods are not invented - they are seen in the cycles of the natural world and the behaviour of the human group. When life becomes stable, man has the space to reflect on it, to speak it aloud, to shape it into symbol.

It is only then that man begins to push into harsher territory. Egypt is not the beginning, but a secondary phase. The desert cannot support unprepared man. It is only after the river has given us the tools of measurement, irrigation, and architectural planning that we dare to enter the Nile valley and impose order upon it. In this sense, Egypt is a ritual re-enactment of Mesopotamian mastery. It is an echo of an earlier triumph, applied to a harsher environment. But necessity still drives it. Only when he knows he can endure does he enter. Man does not seek hardship for its own sake - he is always compelled by the invisible gradient of need.

This pattern reveals itself like a simple pressure gradient. Man moves out from the centre when necessity demands it. He saturates one zone, and then flows into the next. With each saturation comes the birth of culture. But once all territory is filled, the movement turns inward. The cities begin to grow. Population rises. The problem is no longer how to survive, but how to coexist. The creative energy that once mapped rivers now maps social space. Law emerges. Ritual becomes institution. Myth becomes memory.